Open Bible Data Home About News OET Key

A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W XY Z

Tyndale Open Bible Dictionary

Intro ← Index → ©

CONQUEST AND ALLOTMENT OF THE LAND

Terms referring to Israel’s winning of the Promised Land and the distinctive way in which it was divided among the Israelite tribes.

Wiping Out the Canaanites

Many have expressed objection to the apparent cruelty of the Israelites in wiping out the Canaanite people, sometimes calling it barbarism. It should be noted, however, that total annihilation was not practiced everywhere but only in Jericho and Ai and the later punishment of the Amalekites under Saul (1 Sm 15). As in the earlier conquest of the Midianites (Nm 31:17-18), not all the population was killed. In Deuteronomy 20:10-18 and 21:10-14, a distinction is drawn between the treatment of Canaanites (actually a heterogeneous group, see Dt 20:17) and other captive peoples. With the Canaanites, the command to “save alive nothing that breathes” (v 16, rsv) was given “that they may not teach you to do according to all their abominable practices which they have done in the service of their gods, and so to sin against the Lord your God” (v 18, rsv).

In Abraham’s time the wickedness of the Amorites was not yet “complete” (Gn 15:16), but by Joshua’s time it was. Archaeology has documented the sexual perversions, child sacrifices, idolatry, and cruelty of the Canaanites. The Land of Promise was intended to be swept clean of such abominations so that Israel could live an unhampered life, ordered by the covenant law of their God.

Conquest

The conquest of Canaan by the Israelites is one of the most remarkable events of OT history: a loosely organized nomadic people successfully invaded a long-established culture secure in its protected urban centers. That achievement, according to the Scriptures, was the result of a promise God had made to Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob that their descendants would possess the land (Gn 17:8; 26:4; 28:13; Ex 3:15-17). Dispossession of the pagan inhabitants was a divine judgment on false religion and its associated immorality (Dt 7:1-5).

Scholars who attempt to reconstruct the history of the Conquest face certain problems. Critical scholarship has run into conflict with statements in the Bible at three key points: chronology, rate of occupation, and the issue of Israel’s military annihilation of portions of the population of the Canaanite city-states.

The Conquered Land

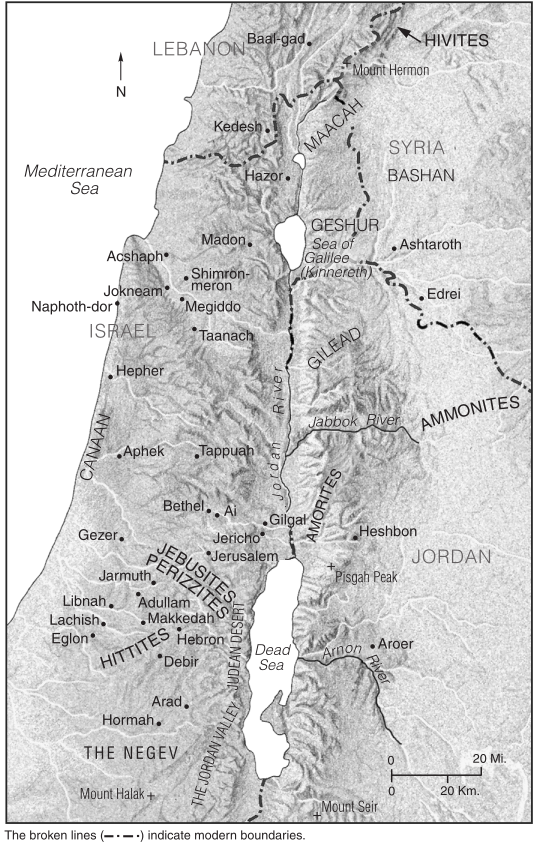

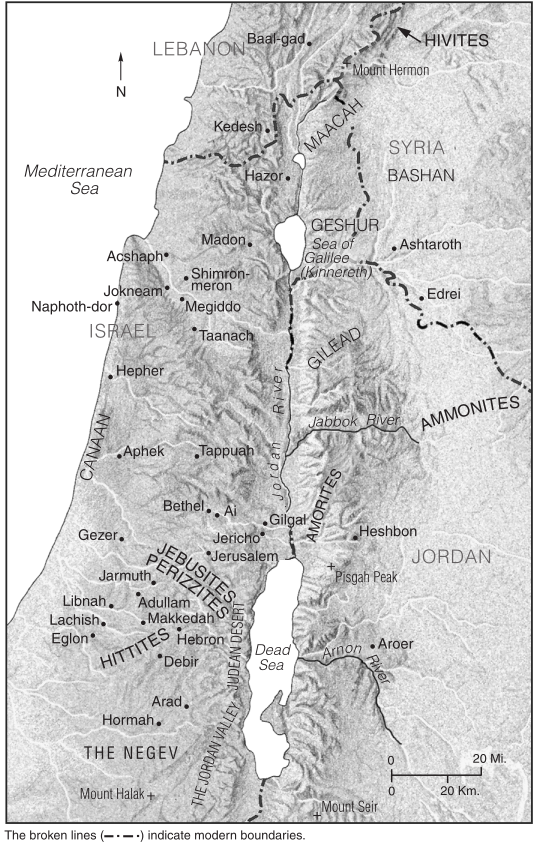

Joshua displayed brilliant military strategy in the way he went about conquering the land of Canaan. He first captured the well-fortified city of Jericho to gain a foothold in Canaan and to demonstrate the awesome might of the God of Israel. Then he gained the hill country around Bethel and Gibeon. From there he subdued towns in the lowlands. Then his army conquered important cities in the north, such as Hazor. In all, Israel conquered land both east and west of the Jordan River, from Mt Hermon in the north to beyond the Negev to Mt Halak in the south.

Date

Reference works and scholarly treatments of OT history often suggest a date for the exodus from Egypt in the 13th century BC (1280 BC or later). Several biblical references to that event would seem to call for an earlier date. According to 1 Kings 6:1, construction of Solomon’s temple was begun in the fourth year of his reign, 480 years after the exodus. Since Solomon’s fourth year was about 960 BC, that would place the exodus at 1440 BC. In Judges 11:26-28, when Jephthah, eighth of the named judges, argued with the king of Ammon about Israelite possession of land east of the Jordan River, he indicated that Israel had occupied this territory 300 years. Saul’s accession to kingship about 1020 BC was still some decades off, so the later date proposed for the exodus does not allow sufficient time for the period of the judges. Further, the apostle Paul referred to a period of about 450 years from the exodus to Samuel’s day (Acts 13:20).

Joshua’s Campaigns

A picture of a concentrated period for the Israelite conquest of Canaan is given in the book of Joshua. Yet many scholars insist that an earlier gradual penetration occurred (by Hebrews who supposedly did not accompany Jacob into Egypt), plus an extended mopping-up procedure that continued down to the time of the monarchy. Although the biblical record allows for later acquisitions in some areas (e.g., Megiddo and Beth-shan), there is no valid reason for rejecting the description of the major Conquest given in Joshua 1–12.

The Conquest began on the east side of the Jordan River under Moses. After Moses’ death, Joshua led Israel across the river, capturing first the fortified cities of Jericho and Ai. Those strategic victories provided access to the hill country and drove a wedge into the middle of Canaan. Two major campaigns followed—a southern and then a northern—which won for Israel in six years’ time the key cities of Canaan, defeating 31 kings and concluding the initial and principal stage of the Conquest.

Numbers 32 records the earlier assignment of territory east of the Jordan (Gilead and Bashan, acquired by the defeat of two kings, Sihon of the Amorites and Og of Bashan) to the tribes of Reuben, Gad, and the half-tribe of Manasseh. Though their land had already been acquired, the men of those tribes were obligated to cross the Jordan with the rest to participate in the military conquest of Canaan itself.

Joshua 2–8 records the unusual events of the destruction of Jericho and Ai in the initial thrust westward. Those victories tended to demoralize the remaining cities of the land. Chapters 9 and 10 describe the southern campaign, including the Gibeonites’ procurement of a treaty by deception. Joshua 10, with its account of the remarkable rout of the enemy forces (vv 9-12) and miraculous prolonging of daylight, is the central passage about the southern campaign. In the subsequent battle, an alliance of five Amorite kings was crushed, the kings were killed, and the city-states of the area were destroyed, except for Jerusalem (later captured by David).

In his northern campaign, Joshua confronted a more formidable alliance. Yet even Jabin, the powerful king of Hazor, largest of the Canaanite cities, supported by his local vassals, was no match for Israel’s armies. Joshua 11 describes that phase, then sums up the entire Conquest in verses 16-23 and on through chapter 12.

See also Allotment of the Land.