Open Bible Data Home About News OET Key

A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W XY Z

Tyndale Open Bible Dictionary

Intro ← Index → ©

PERSIA, PERSIANS

Country lying just to the east of Mesopotamia (modern Iraq) and covering virtually the same territory as present-day Iran. It was known in ancient times by various forms of Fars or Pars, which came down to us as Persia. It continued to be known as Persia until 1935, when its name was changed to Iran. The official modern language of the country is Persian, an Indo-European language written in Arabic characters.

Preview

• Geography and Climate

• History

• Persia and the Bible

Geography and Climate

Persia served as a geographical link between inner Asia and the plateau of Asia Minor. It has been described as a triangle set between two depressions, the Persian Gulf on the south and the Caspian Sea to the north. The sides of the triangle are made up of mountain ranges that enclose an area of desert. On the west the Zagros Mountains run northwest-southeast, with many fertile valleys that are suitable for agriculture. Severe summer heat requires that animals be taken to cooler elevations during that season.

On the north is the Elburz range, with Mt Demavend reaching a height of more than 19,000 feet (5,791.2 meters). The most heavily populated area of Persia is Azerbaijan, which, because of routes leading from various northern points, was one of the most accessible parts of the country and therefore had to be protected by strong fortifications.

Farther east, the Elburz becomes the mountains of Khorasan, which also afford easy passage into the country. This district, which has been called the “granary of Iran,” has been susceptible to foreign invasion over the centuries. On the south, the third side of the triangle, is another mountain range, the Makran. Within these ranges is a saline depression, the southern part of which has been regarded as more arid than the Gobi Desert.

One of the important sections of the country was actually an extension of the Mesopotamian plain; this was known in ancient times as Susiana and now is called Khuzistan. Here the capital, Susa, was situated. Adjoining it to the north is a mountain spur that was the location of Luristan, famous for its bronzes. Another plain, near the Caspian Sea, is tropical in climate; because of heavy rainfall, it produces an abundance and variety of food.

Lacking a river like the Nile or the Tigris-Euphrates system, and having no regular seasonal rains as in Palestine, the agriculture of Persia is dependent on irrigation. Rainfall varies dramatically from one region to another and the climate differs markedly with the topography.

In antiquity the lower mountains were heavily forested with many kinds of trees sought for building by the Sumerian kings of Mesopotamia. Alabaster, marble, lapis lazuli, carnelian, and turquoise were used from early times. Iron, copper, tin, and lead were found here. In modern times the oil resources of Iran have been widely exploited.

History

The Medes (a term often used synonymously with Persians, since the two are so closely related) are a people about whom relatively little is known. They were pictured in Assyrian reliefs. It was the Median Cyaxares who teamed up with the Babylonian Nabopolassar to bring about the destruction of Nineveh in 612 BC.

In the seventh century BC, a small kingdom of Persians was established at Parsumash under Achaemenes, after whom the great Persian dynasty was named. Teispes (675–640 BC), the son and successor of Achaemenes, was under the domination of the Medes, who were gathering forces to overthrow Assyria. Trouble for the Medes freed Teispes from their control, and the weakness of Elam enabled him to gain the province of Parsa (modern Fars). The Assyrians under Ashurbanipal destroyed the nation of Elam and came into contact with the Persians under Cyrus I, son of Teispes.

Cambyses, son of Cyrus, married the daughter of the Median king Astyages; their son, Cyrus II the Great (559–530 BC), built a great palace complex for himself at Pasargadae. The Babylonian king, Nabonidus, allied himself with Cyrus against the Medes. Cyrus fought and defeated his grandfather, Astyages, and made the Median capital, Ecbatana, “place of assembly” (Hamadan), his own capital and set up his archives there (cf. Ezr 6:2).

Cyrus, and later Darius, exhibited an attitude of benevolence and generosity toward defeated enemies, a policy that sometimes worked to the disadvantage of the Persians. A capable military leader, Cyrus invaded Asia Minor and defeated Croesus, king of Lydia, and brought the Greek cities of the area into subjection. He then solidified his eastern frontier. In 539 BC he captured Babylon with virtually no resistance and decreed that the exiled Jews could return to Jerusalem to rebuild the temple (Ezr 1:1-4).

The son of Cyrus, Cambyses II (529–522 BC), conquered Egypt. Upon his suicide, the empire nearly disintegrated. Cambyses was succeeded by Darius I the Great (521–486 BC), the son of Hystaspis, satrap of Parthia. Darius put down the internal revolts and consolidated the empire. For efficient administration of his vast empire, he created 20 provinces or satrapies, each under a satrap or “protector of the kingdom.” Other offices were instituted to check on the activities of the satraps. Darius changed the principal capital from Pasargadae to Persepolis, where his building activities were continued by later Achaemenid kings to make a tremendous palace complex. He was a follower of Zoroaster and a worshiper of Ahura Mazda, as were Xerxes and Artaxerxes.

The early victory of Darius over the rebels is commemorated on the famous rock of Bisitun (Behistun). This memorial took the form of reliefs and a long cuneiform inscription in three languages: Persian, Elamite, and Akkadian. A copy of these records was made by Henry C. Rawlinson in 1855 at considerable risk, for the monument was difficult to approach, situated some 500 feet (152.4 meters) above the plain. This accomplishment played a large part in the deciphering of languages in the cuneiform script. During the later part of Darius’s reign, he suffered defeat at the hands of the Greeks at Marathon (491 BC). Upon his death, Darius was buried in a rock-cut tomb at Naqsh-i-Rustam, a short distance northeast of Persepolis. This was a memorial consisting of reliefs and a trilingual inscription that lauds his person and reign. Later kings were buried in tombs cut in the same cliff.

Darius was succeeded by his son Khshayarsha, better known as Xerxes (485–465 BC). An inscription at Persepolis lists the nations subject to him at the time of his accession and confirms his devotion to Ahura Mazda. During his rule, the Persian fleet was defeated at Salamis (480 BC).

Artaxerxes I Longimanus (Artakhshathra, 464–424 BC) was followed by Darius II (423–405), Artaxerxes II Mnemon (404–359), Artaxerxes III Ochus (358–338), Arses (337–336), and finally Darius III (335–331).

The loss of the empire has been attributed to the cowardice of Darius III, whose armies were defeated by Alexander the Great at Issus in 333 BC and ultimately at Gaugamela, near modern Erbil (Arbela) in 331 BC. Upon the death of Alexander in 323 BC, Persia became the lot of Seleucus, one of his generals. Persian sources say little of the period between Darius III and the beginnings of Sassanian rule in the early third century AD.

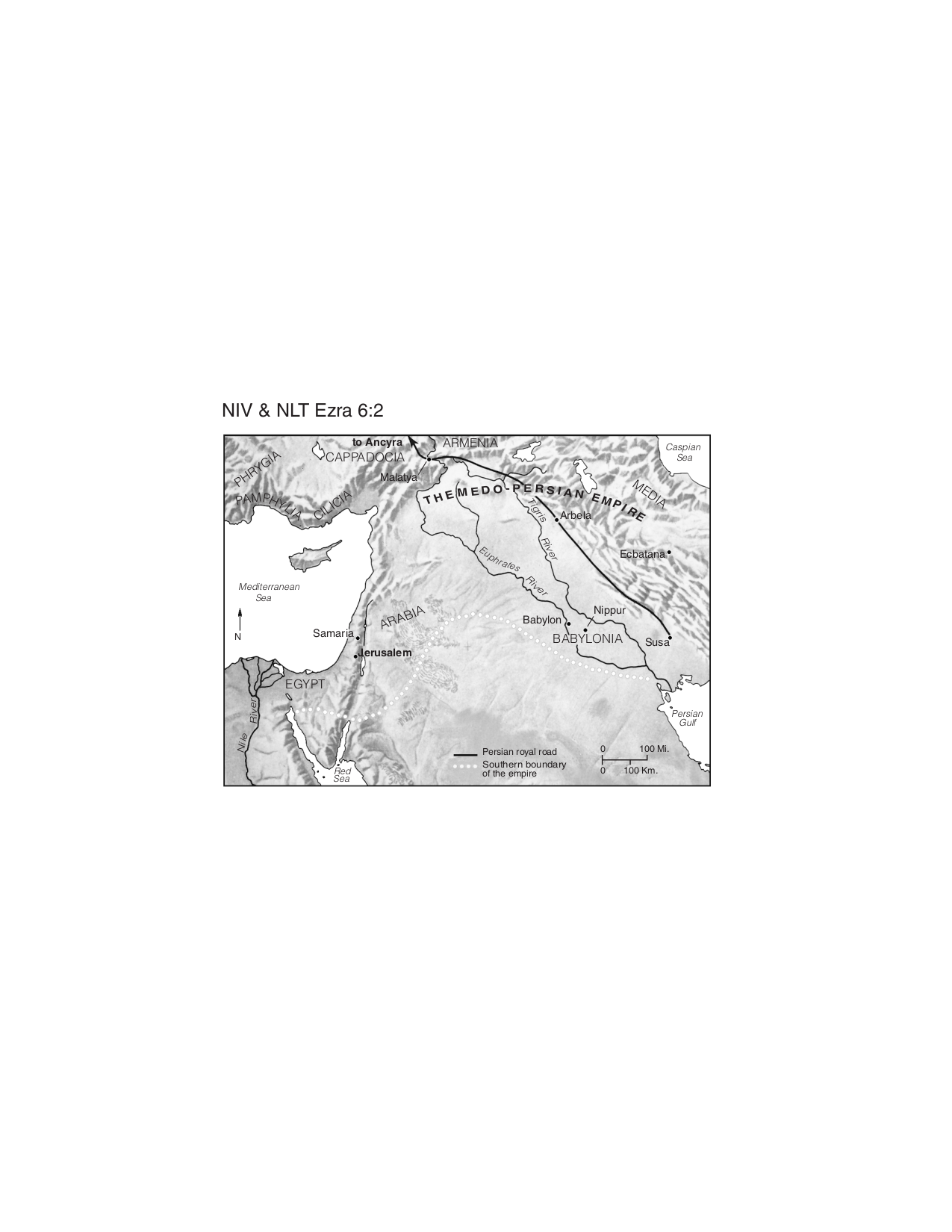

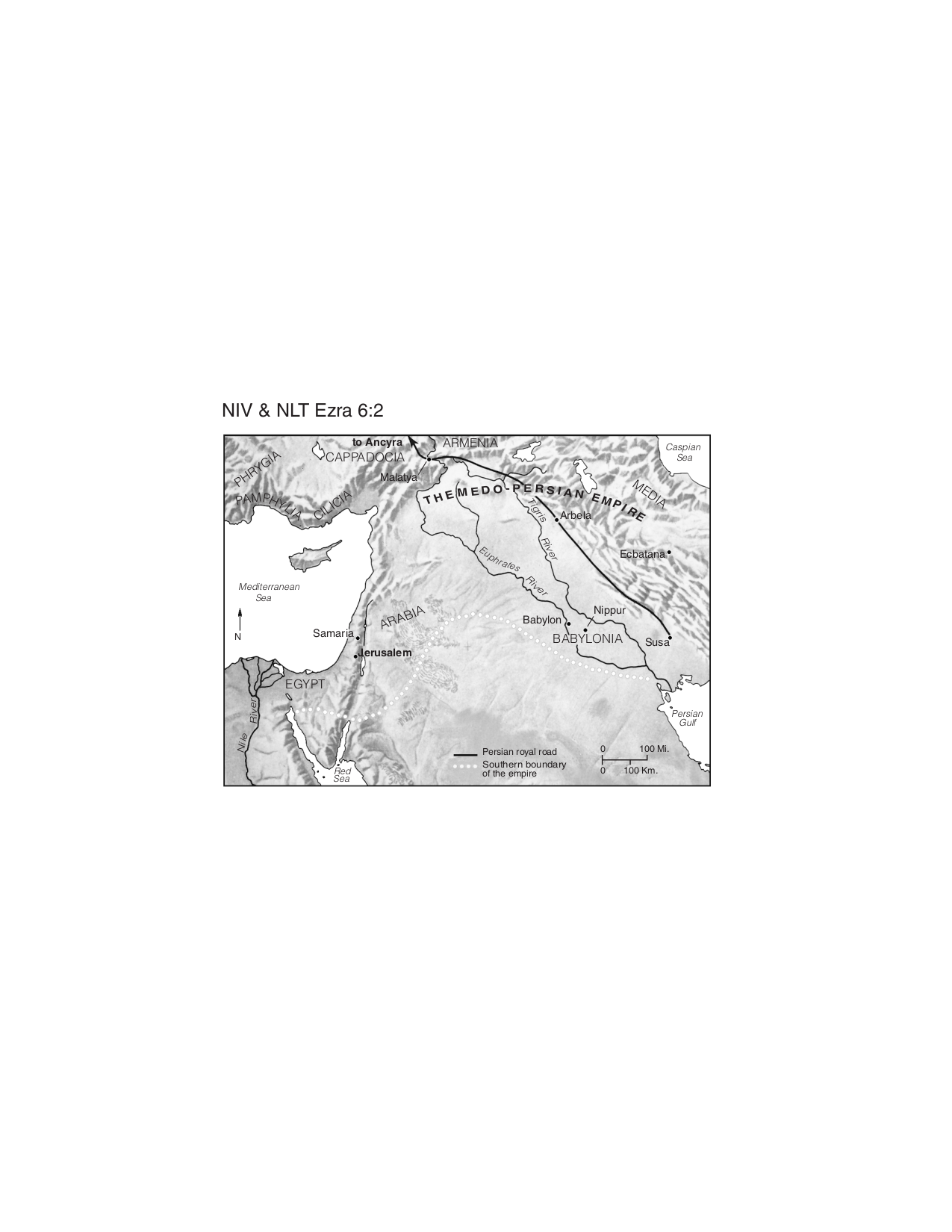

The Medo-Persian Empire

The Medo-Persian Empire included the lands of Media and Persia, much of the area shown on this map and more. The Jewish exiles were concentrated in the area around Nippur in the Babylonian province. The decree by King Cyrus that allowed the Israelites to return to their homeland and rebuild the temple was discovered in the palace at Ecbatana.

Persia and the Bible

The biblical references to Persia occur in the later period of OT history and in the writings of the prophets who ministered during that time. The earliest mention is the reference to Cyrus in Isaiah 44:28–45:1, a passage that has confounded scholars who have felt that the prophecy could not be so precise. This predictive prophecy was given to Isaiah by God more than 150 years before Cyrus captured Babylon and decreed the return of the captive Jews to Jerusalem.

The chronological notations in Daniel, Ezra, Nehemiah, Zechariah, Haggai, and Esther enable us to set chronological markers with some degree of certainty. The first year of Cyrus’s reign over Babylon (Ezr 1:1) may be fixed at 538 BC. The rebuilding of the temple met with opposition from enemies of the Jews in the time of Cyrus and Darius (Ezr 4).

It was at this time that the prophets Haggai and Zechariah encouraged the Jews and urged the completion of the temple. Haggai 1:1 places the message of that prophet on the first day of the sixth month of the second year of Darius I. That translates into August 29, 520 BC. Similarly, Zechariah 1:1 is dated to the eighth month of the year, that is, October/November 520 BC. The letter that was sent to Darius concerning the decree for rebuilding the temple (Ezr 5:6-17) brought about a search of the royal archives that Cyrus had set up at Ecbatana (cf. 6:1-2). The finding of the decree of Cyrus enabled the Jews to complete the temple project, which was finished on March 12, 515 BC (the third day of the month Adar in the sixth year of Darius, Ezr 6:15).

The work of Nehemiah occurred in the reign of Artaxerxes I Longimanus. Nehemiah’s request that he be allowed to return to Jerusalem to rebuild the wall was made in the month of Nisan in the 20th year of Artaxerxes (Neh 2:1, April/May 445 BC). This building project also met with strong opposition. The date is generally confirmed by a letter from the 17th year of Darius II (408 BC) and found among the Elephantine papyri in Egypt. Two personal names found in Nehemiah also occur in this letter: the sons of Sanballat, Nehemiah’s most virulent enemy (cf. Neh 2:19; 4:1-8), and Johanan the grandson of Eliashib, who was high priest at Jerusalem when Nehemiah arrived there (3:1). Another letter among these papyri grants Persian authority to the Jews at Elephantine to celebrate the Passover according to their custom.

The book of Esther is set in the time of King Ahasuerus, who is Xerxes, referred to in Ezra 4:6 between Darius and Artaxerxes. The Hebrew Ahasuerus represents Khshayarsha, whom the Greeks called Xerxes. On the other hand, the Septuagint has Artaxerxes, and Josephus names Artaxerxes as the king mentioned in the book of Esther. Esther provides a number of details of the life and customs of Persian royalty.

Persia also figures in the prophecies of Ezekiel, where Persia is named among the armies of Tyre (Ez 27:10). It is also listed as an ally of Gog in the invasion of Israel (38:5). The recorded history in Daniel refers to Persia (Dn 10:1), as do the prophecies of that book (8:20; 11:2).

See also Postexilic Period; Medes, Media, Median.