Open Bible Data Home About News OET Key

A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W XY Z

Tyndale Open Bible Dictionary

Intro ← Index → ©

EXODUS, The

Departure of Israel from Egypt led by Moses. The exodus was one of the most significant events in the history of the Hebrews. It was a unique demonstration of God’s power on behalf of his people, who were working under conditions of forced labor for the Egyptians. So dramatic were the circumstances in which the exodus occurred that they were mentioned frequently in subsequent OT periods. When the Hebrews were oppressed, they looked back to that great historical event and trusted God for future liberation.

The historicity of the exodus from Egypt is, beyond question, one of the pivotal historical and religious points of the Jewish tradition. It is quite another matter, however, to assign a firm date to the event, partly because certain scriptural references can be interpreted in various ways, and partly because little archaeological evidence from Egypt exists that bears on the question. Since the Egyptians regularly ignored defects in their records and defaced inscriptions belonging to unpopular fellow countrymen, it is improbable that anything approaching an Egyptian literary record of the exodus will ever be obtained. Much of the information regarding the date of the exodus is therefore inferential in character, and that presents biblical historians with one of the most complex problems of chronology.

Date of the Exodus

Determining the date of the exodus has long been a problem for biblical scholars. At the beginning of the 20th century many scholars, both liberal and conservative, placed the date toward the end of the 13th century BC. Not all of them agreed that the exodus was a single event, however. Some believed that the Hebrews entered Palestine twice at widely separated times. But such a view disregards the biblical account.

According to Exodus 12:40, the length of time that Jacob’s descendants resided in the land of Egypt was 430 years. God had already predicted that interval of time to Abram (Gn 15:13). The Genesis prophecy, however, did not indicate when that occupation would begin.

The Septuagint (the first Greek translation of the OT), in its version of Exodus 12:40, reduced the period of occupation in Egypt to 215 years. That may mean that two traditions of exodus history existed. A stay of four centuries may have been reckoned from the period when an Asiatic people known as the Hyksos invaded Egypt (c. 1720 BC) and governed it for about a century and a half. The period of 215 years preserved in the Septuagint may be the interval of time between the expulsion of the Hyksos and the exodus itself.

More specific information from Israel’s early monarch, however, has a bearing on the time when the Hebrews escaped from Egypt. First Kings 6:1 indicates that Solomon constructed the temple in Jerusalem 480 years after the Israelites were led out of Egypt by Moses. Taking that figure at face value, and allowing a date of 961 BC for the reference to Solomon, the exodus would have occurred about 1441 BC. On the basis of such biblical data, some scholars argue for a 15th-century BC date for the exodus, connecting it with the reign of Pharaoh Amenhotep II (c. 1450–1425 BC) as the time of Israel’s oppression. Other scholars feel equally persuaded that the exodus occurred in the 13th century BC.

Route of the Exodus

The biblical data concerning the route of the exodus placed the beginning of the flight at Rameses (Ex 12:37). This place was identified with Tanis by early investigators, but more recent work suggests Qantir, about 17 miles (27.4 kilometers) southwest of Tanis, as the preferred site. It now seems certain that the monuments at Tanis apparently erected by Ramses have been misunderstood. None of those monuments seems to have originated at Tanis but were brought there by later kings who reused them. Thus the primary evidence for identifying Tanis with Ramses has proved to be misleading. Excavations at Qantir, on the other hand, have revealed indications of palaces, temples, and houses, all of which were local in origin. Such evidence suggests that Qantir, not Tanis, was the Rameses from which the exodus commenced. In addition, Rameses, unlike Tanis, was located beside a body of water (the “Waters of Re” mentioned in Egyptian sources), which again conforms to the biblical account.

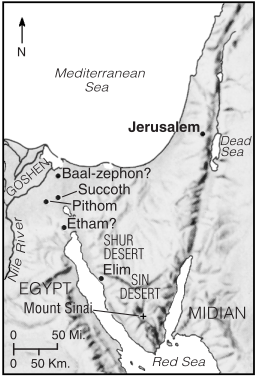

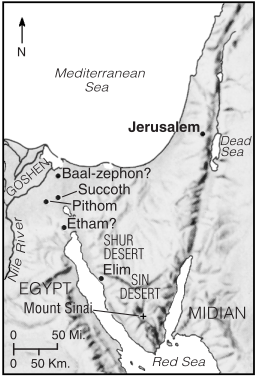

Key Places in the Exodus

The Israelites left Succoth and camped first at Etham before going toward Baal-zephon to camp by the sea (14:2). God miraculously brought them across the sea, into the Shur Desert (15:22). After stopping at the oasis of Elim, the people moved into the Sin Desert (16:1).

From Rameses the Israelites moved to Succoth (Nm 33:5), generally identified with Tell el-Maskhuta, a fortification in the eastern area of the Wadi Tumeilat, west of the Bitter Lakes. From Succoth they journeyed to Etham (Ex 13:20), which was on the frontier of the wilderness of Shur. The Hebrews were then instructed to return northwestward so that the stage might be set for the events of the exodus proper. Accordingly, they encamped between Migdol and the “sea,” close to two sites called Pi-hahiroth and Baal-zephon. Pi-hahiroth may have been a lake, the “Hi-waters,” mentioned in Egyptian documents. Baal-zephon has been identified with the later Tahpanhes (Tell Defenneh) near Qantara. Both identifications lack certainty, but these places were probably located in the northeast part of the Nile River delta area near Lake Menzaleh. The “sea” was a lake of papyrus reeds, described in Exodus 15:22 as the “reed sea,” the English equivalent of an Egyptian phrase meaning “papyrus marshes.” In most English translations from the time of the KJB onward, the Hebrew for “reed sea” was rendered as “Red Sea.”

Sources from the 13th century BC mention the existence of a large papyrus marsh in the area of Rameses that could be the one referred to in Scripture. Other suggestions equate the “reed sea” with the southeast extension of Lake Menzaleh, or with some body of water just to the south, perhaps Lake Ballah, all of which are reasonably close to each other. The topography can never be determined with complete accuracy, since the construction of the Suez Canal drained a series of lakes and swamps, of which the “reed sea” was possibly one.

At the camp at Migdol, the Hebrews were overtaken by the pursuing Egyptians and appeared to be trapped hopelessly. Then the Lord worked one of the greatest miracles of history. He first prevented the Egyptians from encountering the Hebrews that night by means of a pillar of cloud (Ex 14:19-20). Moses raised his rod over the reed sea, and a strong east wind blew on the water all night. By morning a strip of the sea bottom had been exposed and dried out, enabling the Israelites to flee across it. When the Egyptians pursued their former slaves, Moses again raised his rod, the wind ceased, and the waters returned to normal levels, trapping the Egyptian chariots and soldiers and causing heavy losses. A victory song (Ex 15:1-21), typical of ancient Near Eastern customs in warfare, was the liberated captives’ immediate response to God.

The parting of the waters is a phenomenon that has been observed periodically in various parts of the world. It always occurs in the same manner and involves a strong wind displacing a body of water. Shallow lakes, rivers, or marshes are parted readily under such conditions. The scriptural reference to the east wind indicates that God miraculously employed that natural phenomenon to rescue his people.

Having escaped successfully from the Egyptians, the Hebrews journeyed to the wilderness of Shur, three traveling days away from the bitter waters of Marah (Ex 15:22-25). In Numbers 33:8 the wilderness of Shur is identified with Etham, which the Israelites had already left. Thus it appears that they had moved north from Migdol, after which they moved south again to the wilderness in the area of Etham. The Israelites were not able to go into the Sinai Peninsula along the normal routes, which were guarded by Egyptian fortresses. In addition, they had been instructed not to travel along the northward road going to the “way of the land of the Philistines” (Ex 13:17) into Canaan. Consequently, the best means of satisfying both conditions was to move southeastward to Sinai as unobtrusively as possible, taking care to avoid the access routes to Serabit el-Khadem in the central peninsula region, where the Egyptians mined turquoise and copper. The narratives of Numbers 33:9-15 show that the Israelite camps were located in an area south of the “reed sea,” proving that the refugees had not taken the northerly, or “Philistine,” route.

The Exodus Theme in Scripture

Old Testament

The motif of deliverance from captivity in Egypt became etched indelibly upon the Hebrew mind, particularly since it was reinforced each year by the celebration of the Passover meal (Ex 12:12-14). At each celebration thereafter the Hebrews were made aware that they had once been captives, but by the provision and power of God they were now free people—an elect nation and holy priesthood (Dt 26:19).

In later periods psalms were written recounting Israel’s history in the light of the great liberating event of the exodus (Pss 105; 106; 114; 136). Those compositions resound with triumph and thanksgiving. Hebrew accounts of the bondage in Egypt depict the rigorous life, the oppression, and the hard labor. It is now known that there were a number of foreign groups in Egypt at the time, and that the corporal punishment suffered by the Hebrews was a normal feature of everyday Egyptian life. In short, there was no discrimination against the Hebrews as a group; instead, they enjoyed the dubious distinction of being treated like ordinary Egyptian workers. Ever after, when they were oppressed, the Hebrews could look back to the great miracle of the exodus and believe that what God had done once he could do again. That was of great consolation to the faithful exiles weeping by the waters of Babylon (Ps 137:1) as they looked forward to another exodus when God would lead them in triumph from a destroyed Babylon (v 8) back to Palestine.

New Testament

God’s mighty work at the time of the exodus was recalled on a few occasions by NT writers, even though Christ had been sacrificed as “our Passover lamb” (1 Cor 5:7, niv) by that time. In his speech before the Jerusalem Council, Stephen gave a traditional recital of OT history, mentioning the event of the Red Sea (Acts 7:36) as part of a demonstration of God’s power to change human affairs. The apostle Paul used the experience of the exodus to remind his hearers that many who were delivered from oppression at that time never reached the Promised Land (1 Cor 10:1-5). Instead of committing themselves wholly to God in trust and obedience, the Israelites fell victim to temptations of various kinds in the wilderness. Thus, Paul stressed that since it is possible for Christians to become castaways (9:27), they should cling to Christ the Rock and take their spiritual responsibilities seriously. In Hebrews 11:27-29 another historical recital lists the heroes of faith, mentioning especially Moses and his role at the exodus.

See also Exodus, Book of.