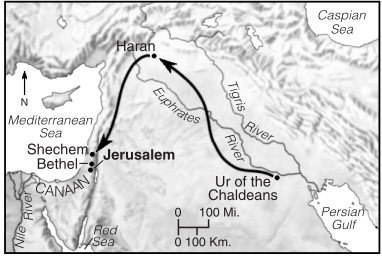

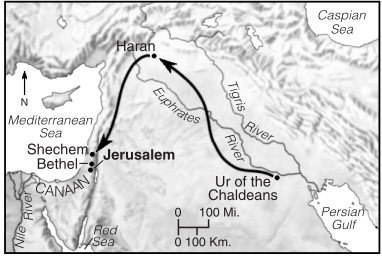

Abram’s Journey to Canaan

Abram, Sarai, and Lot traveled from Ur of the Chaldeans by way of Haran.

Open Bible Data Home About News OET Key

OET OET-RV OET-LV ULT UST BSB MSB BLB AICNT OEB WEBBE WMBB NET LSV FBV TCNT T4T LEB BBE Moff JPS Wymth ASV DRA YLT Drby RV SLT Wbstr KJB-1769 KJB-1611 Bshps Gnva Cvdl TNT Wycl SR-GNT UHB BrLXX BrTr Related Topics Parallel Interlinear Reference Dictionary Search

A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W XY Z

ABRAHAM

One of the Bible’s most significant personalities, whom God called from the city of Ur to become patriarch of God’s own people.

Abram’s Journey to Canaan

Abram, Sarai, and Lot traveled from Ur of the Chaldeans by way of Haran.

Abraham’s name was originally Abram, meaning “[the] father is exalted.” When he was given that name by his parents, they were probably participants in the moon cult of Ur, so the father deity suggested in his old name could have been the moon god or another pagan deity. God changed Abram’s name to Abraham (Gn 17:5), partly, no doubt, to indicate a clear-cut separation from pagan roots. The new name, interpreted by the biblical text as meaning “father of a multitude,” was also a statement of God’s promise to Abraham that he would have many descendants, as well as a significant test of his faith in God—since he was 99 years old at the time and his childless wife was 90 (Gn 11:30; 17:1-4, 17).

Abraham’s Life

The story of Abram begins in Genesis 11, where his family relationships are recorded (Gn 11:26-32). Terah, Abram’s father, was named after the moon deity worshiped at Ur. Terah had three sons, Abram, Nahor, and Haran. Haran, the father of Lot, died before the family left Ur. Terah took Lot, Abram, and Abram’s wife, Sarai, from Ur to go to Canaan but settled at the city of Haran (v 31). It is stated in Acts 7:2-4 that Abraham heard the call of God to leave for a new land while he was still in Ur.

A note of major importance to the course of Abram’s life is found in Genesis 11:30: “Sarai was not able to have any children” (NLT). The problem of Sarai’s barrenness provided the basis for great crises of faith, promise, and fulfillment in the lives of Abram and Sarai.

Abraham, the Friend of God

Referred to as the “friend of God” (2 Chr 20:7; Jas 2:23, NLT), Abraham played an important role in Hebrew history. Through Abraham’s life, God revealed a program of “election” and “covenant,” which culminated in the work of Jesus Christ. God said to Abraham, “All the families of the earth will be blessed through you” (Gn 12:3, NLT). Centuries later, the apostle Paul explained that the full import of God’s promise was seen in the preaching of the gospel to all nations and the response of faith in Christ, which signifies believers from all families of the earth as sons of Abraham (Gal 3:6-9).

After Terah’s death, God told Abram, “Leave your country, your relatives, and your father’s house, and go to the land that I will show you.” This command was the basis of a “covenant,” in which God promised to make Abram the founder of a new nation in that new land (Gn 12:1-3, NLT). Abram, trusting God’s promise, left Haran at the age of 74. Entering Canaan, he went first to Shechem, an important Canaanite royal city between Mt Gerizim and Mt Ebal. Near the oak of Moreh, a Canaanite shrine, God appeared to him (12:7). Abram built an altar at Shechem, then moved to the vicinity of Bethel and again built an altar to the Lord (12:8). The expression “to call on the name of the Lord” (rsv) means more than just to pray. Rather, Abram made a proclamation, declaring the reality of God to the Canaanites in their centers of false worship. Later Abram moved to Hebron by the oaks of Mamre, where again he built an altar to worship God. Another blessing given in a vision (15:1) led Abram to exclaim that he was still childless and that Eliezer of Damascus was his heir (15:2). Discovery of the Nuzi documents has helped to clarify that otherwise obscure statement. According to Hurrian custom, a childless couple of station and substance would adopt an heir. Often a slave, the heir would be responsible for the burial and mourning of his adoptive parents. If a son should be born after the adoption of a slave-heir, the natural son would of course supplant him. Thus God’s response to Abram’s question is directly to the point: “No, your servant will not be your heir, for you will have a son of your own to inherit everything I am giving you” (Gn 15:4, NLT). God then made a covenant with Abram insuring an heir, a nation, and the land.

Abraham’s Bosom

Figure of speech probably derived from the Roman custom of reclining on one’s left side at meals with the guest of honor at the bosom of his host (cf. Jn 13:23-25). It was used by Jesus in the story of Lazarus as a description of paradise (Lk 16:22-23). In rabbinical writings, as well as 4 Maccabees 13:17, righteous people were thought to be welcomed at death by Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob. Jesus, probably aware of this, was also alluding to the “messianic banquet,” an image he used a number of times. Thus, in the world to come, the godly poor like Lazarus would not only be welcomed by Abraham but would occupy the place of honor next to him at the banquet.

Abram was 86 years old when Ishmael was born. When Abram was 99, the Lord appeared to the aged patriarch and again reaffirmed his covenant promise of a son and blessing (Gn 17). Circumcision was added as the seal of covenantal relationship (17:9-14), and at that point the names Abram and Sarai were changed to Abraham and Sarah (17:5, 15). Abraham’s response to the promise of another son was to laugh: “Then Abraham bowed down to the ground, but he laughed to himself in disbelief. ‘How could I become a father at the age of one hundred?’ he wondered. ‘Besides, Sarah is ninety; how could she have a baby?’ ” (Gn 17:17, NLT).

Genesis 18 and 19 recount the total destruction of two cities of the Jordan plain, Sodom and Gomorrah. Chapter 18 begins with three individuals seeking comfort in the heat of the day. Abraham offered refreshment and a meal to his guests. They turned out to be no ordinary travelers, however, but the Angel of the Lord along with two other angels (18:1-2; 19:1). There is reason to believe that the Angel of the Lord was God himself (18:17, 33). Another announcement of a promised son made Sarah laugh in unbelief and then deny having laughed (18:12-15).

Genesis 21 to 23 form the climax of the story of Abraham. At long last, when Abraham was 100 years old and his wife 90, “the Lord did exactly what he had promised” (Gn 21:1, NLT). The joy of the aged couple on the birth of their long-promised son could not be contained. Both Abraham and Sarah had laughed in unbelief in the days of promise; now they laughed in joy as God had “the last laugh.” The baby, born at the time God promised, was named Isaac (“he laughs!”). Sarah said, “God has brought me laughter! All who hear about this will laugh with me” (Gn 21:6, NLT).

The laughter over Isaac’s birth subsided entirely in the test of Abraham’s faith described in chapter 22, God’s command to sacrifice Isaac. Only when one has experienced vicariously with Abraham the long 25 years of God’s promise of a son can one imagine the trauma of such a supreme test. Just as the knife was about to fall, and only then, did the angel of God break the silence of heaven with the call, “Abraham!” (22:11). The name of promise, “father of a multitude,” took on its most significant meaning when Abraham’s son was spared and the test was explained: “I know that you truly fear God. You have not withheld even your beloved son from me” (Gn 22:12, NLT).

Those words were coupled with a promise implicit in the discovery of a ram caught in the thicket. The Lord provided an alternative sacrifice, a substitute. The place was named “the Lord will provide.” Christian believers generally see the whole episode as looking ahead to God’s provision of his only Son, Jesus Christ, as a sacrifice for the sins of the world.

See also Covenant; Patriarchs, Period of the; Israel, History of; “Abraham’s Bosom”; Sarah #1.