Open Bible Data Home About News OET Key

A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W XY Z

Tyndale Open Bible Dictionary

Intro ← Index → ©

ACTS OF THE APOSTLES, Book of the

NT book presenting the history of the early church and written as a sequel to the Gospel of Luke. In the arrangement of the NT books, Acts comes after the four Gospels and before the Epistles.

Preview

• Author

• Date, Origin, Destination

• Background and Content

• Purpose

Author

The book of Acts does not state clearly who its writer is, but the general consensus is that Luke was its author.

Early church tradition from the second century states that Acts (as well as the third Gospel) was written by a traveling companion and fellow worker of the apostle Paul. That companion is identified in Colossians 4:14 as “Luke, the beloved physician” (nasb) and mentioned among Paul’s coworkers (Col 4:10-17; see also 2 Tm 4:11; Phlm 1:24).

Strong support for the tradition that the author of Acts was a companion of Paul comes from the second half of the book recounting Paul’s ministry. There, several narratives are told in the first person plural:

1. “That night Paul had a vision. He saw a man from Macedonia in northern Greece, pleading with him, ‘Come over here and help us.’ So we decided to leave for Macedonia at once, for we could only conclude that God was calling us to preach the Good News there” (16:9-10, NLT).

2. “They went ahead and waited for us at Troas . . . we boarded a ship at Philippi in Macedonia and five days later arrived in Troas, where we stayed a week” (20:5-6, NLT).

3. “When the time came, we set sail for Italy” (27:1, NLT).

These “we” sections (16:9-18; 20:5–21:18; 27:1–28:16) sound like part of a travel narrative or diary written by an eyewitness who accompanied Paul from Troas to Philippi on his second missionary journey; from Philippi to Miletus on the third; from Miletus to Jerusalem; and from Caesarea to Rome. Since the style and vocabulary of these travel narratives resemble those of the rest of the book, it is highly probably that the diarist was also the author of the entire book.

The sophisticated literary style and polished use of the Greek language in the book, as well as the fact that it is addressed to someone called Theophilus (possibly a high-ranking Roman official), provide strong support for the tradition that Luke was a gentile convert to Christianity. His consistent and frequent use of the Greek OT may indicate that he had been a gentile “God-fearer” before conversion to the new faith.

Date, Origin, Destination

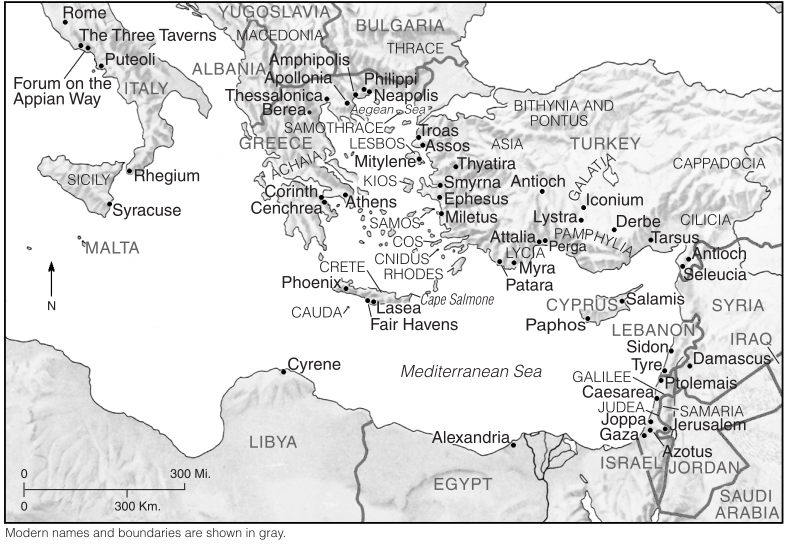

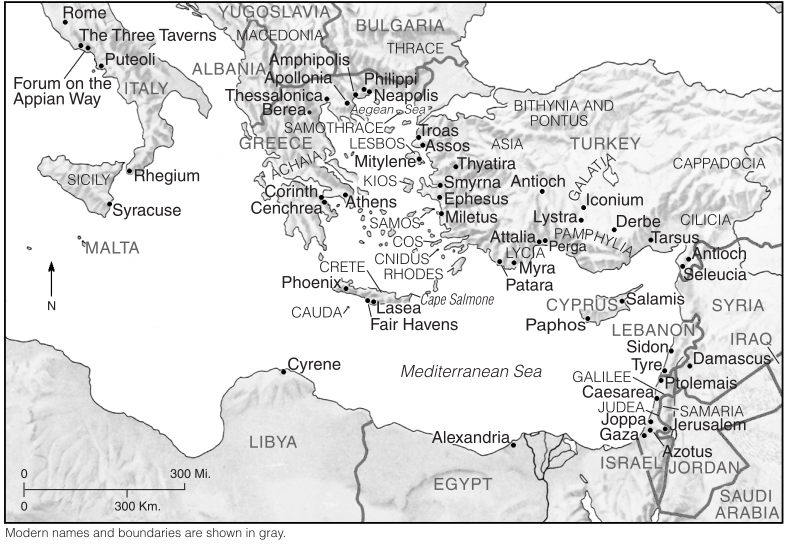

Key Places in Acts

The apostle Paul, whose missionary journeys fill much of this book, traveled tremendous distances as he tirelessly spread the gospel across much of the Roman Empire. His combined trips, by land and ship, equal more than 13,000 miles (20,917 kilometers).

The question of the date and place of the origin of Acts continues to be debated. There are no clear indications in the book itself. With regard to its destination, however, Luke did not leave any doubt. In the opening verse he addresses a certain Theophilus, to whom he had already written an earlier book about the life of Jesus. There can be no doubt that he was referring to the work we know as the Gospel of Luke. In the preface to that Gospel (Lk 1:1-4), Luke clearly stated his purpose for writing and addressed his account to the “most honorable Theophilus.” It is not clear who that person was. Some interpreters think that Theophilus (which means “dear to God” or “lover of God”) stands for Christian readers in general rather than any specific individual. However, the designation “most honorable” argues against such an assumption. That ascription was a common title of honor, designating a person with official standing in the Roman sociopolitical order (cf. use of the title for Felix, Acts 23:26; 24:2; and for Festus, 26:25). It is thus likely that Luke intended his two-volume work for an official representative of Roman society.

When was Acts written? Some scholars date it in the last quarter of the first century. Since the Gospel was written first, and since Luke based his story of Jesus on eyewitness accounts and written sources (among which was possibly the Gospel of Mark, probably written in the 60s), Acts should not be dated much before AD 85. Proponents of such a late date claim support from the theology of Acts, which they see as picturing a Christian church settled into history, adjusted to the prospect of a lengthy period before the Lord’s return. Since expectation of the Lord’s imminent return was fanned into a living flame by the Jewish revolt and the fall of Jerusalem in AD 70, time must be allowed for that flame to have died down a bit.

Other scholars date Acts around AD 70 or shortly thereafter. The Jewish rebellion of AD 66–70, which culminated in the destruction of Jerusalem, brought the Jewish faith—legal until then—into disrepute. The Christian movement, which had been accepted as a Jewish sect, became suspect. Christians were increasingly charged with being enemies of Rome. A study of Acts shows that among a number of purposes (see below), Luke seems to have been defending the Christians against the charge of hostility toward the state. He showed how Roman officials repeatedly testified to the complete innocence of Christians and above all else of Paul (16:39; 18:14-17; 19:37; 23:29; 25:25; 26:32). Luke also made it clear that Paul was allowed to carry on his mission with full approval of Roman officials in the very heart of the imperial capital (28:16-31).

A still earlier date, closer to Paul’s Roman imprisonment (early 60s), has been advocated by a number of scholars. There are two compelling reasons: (1) The abrupt ending of Acts, describing Paul carrying on a ministry in Rome before his trial had commenced, may indicate that Luke was writing at that point. It is possible, of course, that Luke ended his story with Paul preaching the gospel in Rome because one of his purposes had been accomplished: namely, showing how the gospel spread from Jerusalem to Rome. But it seems highly unlikely that Luke would close his history without Paul’s defense of the gospel before Caesar himself if that had already happened. (2) The most appropriate period for Luke’s history, with its defense of the Christian movement against all kinds of accusations from both Jews and Gentiles, is the period when Christianity was becoming suspect but was not yet proscribed. That was the time before the start of the persecutions under Nero in AD 64. The early date would correspond with the contention that Luke was with Paul during his Roman imprisonment and that he wrote his history in Rome while waiting for Paul’s trial to begin. It is possible that Luke’s work was partially intended to influence the verdict. Luke presented a picture of Christianity and of Paul that he hoped would enable Paul to continue his work among the Gentiles.

Background and Content

Luke grounds his documentary of the rapid expansion of Christianity in the history of the Roman Empire and Palestine during the three decades from AD 30 to 60. Some brief historical and geographical considerations will aid in understanding Luke’s history.

Acts 1–12 reports the beginnings of the Christian movement within the imperial province of Syria, which included Judea and Samaria. In the first century AD, those regions were generally governed by Roman procurators or puppet kings. At the time of Jesus’ death and resurrection (c. AD 30), Pontius Pilate was procurator in Judea and Samaria (AD 26–36). Galilee was ruled by King Herod Antipas (4 BC–AD 39). Tiberius was emperor of the Roman Empire (AD 14–37). The account of Acts 1–12 took place in the period AD 30–44.

The conversion of Saul (Acts 9) is generally dated in AD 33. After Saul’s conversion and departure to his native Tarsus, the church evidently enjoyed a period of tranquility, consolidating its gains and growing steadily (9:31–11:26). It can be assumed, from Galatians 1:18-21 and the existence of Christian communities that Paul and Silas visited on the second missionary tour (Acts 15:40-41), that Paul was not idle during that decade, but intensely involved in the mission to the Gentiles. (After Acts 13:9, the name “Saul” is dropped from the narrative.)

In AD 41, Claudius became emperor of Rome and installed Herod Agrippa I as king of the Jews. (The procurator Pontius Pilate had been removed several years earlier for inept administration of the region.) Agrippa I was grandson of Herod the Great and his Jewish princess Mariamne. Because of his Jewish roots, he was more popular with his subjects than the former Herods. No doubt it was his desire to increase that popularity and gain the support of the Jewish religious authorities that led to a renewed outbreak of violence against the Jerusalem church. Acts 12 recounts the execution of James (the brother of the apostle John) and the imprisonment of Peter. The story of Agrippa I’s death (12:20-23) is paralleled in an account by the Jewish historian Josephus, who dates the event in AD 44.

A second event providing a time reference for the unfolding story of the early church is the collection of famine relief in Antioch for Christians in Judea (11:27-29). Luke stated that a severe famine took place (v 28) during the reign of Emperor Claudius (AD 41–54). Josephus, writing his Antiquities at the end of the first century, spoke of a severe famine in Palestine between the years AD 44 and 48. According to Acts 12:25, Barnabas and Paul finished their mission to famine-stricken Christians in Judea after the death of Agrippa I, making it possible to date their mission about AD 45.

At that point in the narrative of Acts, Paul is launched officially into his mission to the Gentiles (13:1-3), for which the history and geography of the larger Roman Empire form the backdrop. The official Roman policy toward the various religions in the empire was one of toleration. That policy, plus use of the Greek language throughout the empire and a phenomenal network of roads and sea routes, paved the way for Paul’s far-ranging missionary work.

The first tour (AD 46–47) took Paul and Barnabas through the island province of Cyprus in the northeastern tip of the Mediterranean Sea and into the province of Galatia, where churches were established in several cities of southern Galatia (Antioch of Pisidia, Iconium, Lystra, Derbe). Galatia is located in Asia Minor, bordered by the Black Sea, the Aegean Sea, and the Mediterranean Sea on its northern, western, and southern sides. Those cities, important colonial outposts for the Romans, contained mixed populations, including large Jewish communities. It was in the synagogues of those communities that Paul launched his missionary efforts, almost always meeting with considerable opposition (chs 13–14).

The deliberation of the Jerusalem Council about differences between Jewish and gentile Christians (ch 15) can be dated in the year AD 48. It was followed by Paul’s second missionary journey, which led him through the already evangelized territory of his native Cilicia, Galatia, and through Troas on the Aegean coast to Macedonia and down into Achaia, the Greek Peninsula (15:40–18:22). Churches were established in the important Macedonian cities of Philippi, Thessalonica, and Beroea.

Paul’s one and a half years in Corinth (18:11) can be dated with some certainty in AD 51–52. An ancient inscription among the ruins of Delphi, a city in central Greece, states that Gallio became proconsul of Achaia in 51. Acts 18:12-17 tells how Paul was accused by antagonistic Jews before Gallio. The implication is that Paul’s adversaries in Corinth felt that a new proconsul could be persuaded to side with their cause. Thus, Paul’s stay in Corinth can be dated around the beginning of Gallio’s proconsulship.

Luke’s account of Paul’s return to Palestine and the beginning of his third missionary tour brings up a fascinating historical question about what happened to the followers of John the Baptist (13:13–19:7). Acts 18:24-28 refers to a learned Jew, Apollos, who was actively teaching about Jesus in the synagogue at Ephesus, but who was apparently not a member of a distinctively Christian community, not having been baptized in the name of Jesus. He was acquainted only with the baptism of repentance practiced by John the Baptist. After Apollos went to Corinth to minister to the young congregation that Paul founded the previous year, Paul went to Ephesus. There he met several disciples of Jesus who, like Apollos, had experienced John’s baptism of repentance, but who had not been baptized as Christians.

Luke’s reference to Apollos and those disciples, as well as several passages in the Gospels, indicate that the movement begun by John the Baptist did not simply come to an end when Jesus began his ministry. Evidently John continued to baptize until his death (Jn 3:22-24), and many of his disciples maintained John’s work after his death. Probably both Apollos and the disciples at Ephesus were products of the continuing ministry of John’s disciples. Eventually they were introduced to “the way of the Lord” (18:25). Their lack of knowledge about a distinctive Christian baptism or about the reality of the Holy Spirit (19:2-4) shows how much diversity in both belief and practice existed in early Christianity.

Paul’s third missionary tour began with a three-year ministry in Ephesus (19:1–20:1), continued with a visit to churches established on the previous journey (20:2-12), and came to a climax with his arrest in Jerusalem (Acts 21). It took place in the mid-50s (AD 53–57). Paul’s arrest in Jerusalem and arraignment before the provincial governor, Felix, in Caesarea (23:23–24:23) must be dated about 57. After Paul had spent two years under house arrest, no doubt prolonged by Felix to gain favor with Jewish subjects, Felix was replaced by Porcius Festus (AD 59–60). Josephus noted that Felix was recalled because of an outbreak of civil strife between Jewish and gentile inhabitants of Caesarea and Felix’s unwise handling of the situation.

The new procurator, Festus, was uncertain about what to do with his prisoner. The Jewish leadership sought to seize that opportunity, aware of the desire of new procurators to gain popularity with their subjects (25:1-9). Realizing the threat, Paul appealed his case to the highest court of the empire, presided over by Caesar himself (25:10-12).

Festus was then left with a problem. He had to send with his prisoner a report to the emperor, clearly outlining the charges. Since he did not really comprehend the case (25:25-27), he sought the advice of Herod Agrippa II, who with his sister had come to Caesarea to pay their respects to the new imperial governor of Palestine (25:13). Agrippa II was the son of Herod Agrippa I and, at least in theory, a Jew. He ruled over parts of Palestine from AD 50 to 100 and had been given the right to appoint the Jewish high priests. His familiarity with Jewish religious traditions and the Law thus put him in a better position to understand Jerusalem’s case against Paul. The outcome of Paul’s appearance before Festus and Agrippa (26:1-29) was recognition of Paul’s innocence (26:31). Yet Paul’s appeal to Rome had to be honored; the law governing such cases had to be followed (26:32).

Paul’s relative freedom during the next two-year period (28:30) seems unusual but was a rather common practice in Roman judicial proceedings, especially for Roman citizens who had appealed to the emperor. There is no good reason to believe that Paul was executed at the time when Luke’s narrative ends (c. AD 61–62). The great fire of Rome and Nero’s subsequent persecution of Christians were still a few years away (AD 64). It is likely that the case against Paul was dismissed, especially in light of the favorable verdict by Festus and King Agrippa. It is also likely that Paul was executed during the later, more general persecution of Christians. Such a sequence would correspond with the tradition cited by Eusebius, a fourth-century church historian, that Paul resumed his ministry and later suffered martyrdom under Nero.

Purpose

In the preface to the Gospel, intended to cover the second volume also, Luke told Theophilus (and the audience he represented) that he had set out to write an accurate, orderly account about the beginnings of the Christian movement in the ministry of Jesus of Nazareth (Lk 1:1-4). The opening lines in Acts indicate that the narrative beginning with Jesus of Nazareth (vol 1) is continuing and that Luke’s second volume intends to trace the story from Palestine to Rome (Acts 1:1-8).

While recounting this story, Luke attempted to defend the Christian movement against false charges brought against it. A number of misconceptions attended the birth and growth of the Christian movement. One concerned the relationship between the new faith and Judaism. Many, both within the church and among Roman officials, understood the Christian faith as no more than a particular expression of, or sect within, Judaism. Against that restricted notion, Luke-Acts strikes a universal note. The Gospel proclaims Jesus as Savior of the world (Lk 2:29-32). In Acts, Stephen’s defense before the Jewish council (ch 7), Peter’s experience in Joppa with Cornelius (ch 10), and Paul’s speech at Athens (ch 17) all demonstrate that Christianity is not merely a Jewish sect, some narrow messianic movement, but rather a universal faith. Another problem was popular identification of the new faith with the various religious cults and mystery religions in the Roman Empire. The accounts of the early church’s conflict with Simon the magician (ch 8) and of Paul and Barnabas’s rejection of an attempt to worship them at Lystra (ch 14) undermine the popular charge of superstition. Also, Christianity is not a mystery cult in which esoteric, secret rites bring a worshiper into union with the divine. The Lord worshiped by Christians, said Luke, belongs to real history; he lived his life in Palestine in the then-recent past, openly, for all to observe (see the speeches of Peter and Paul in Acts 2; 10; 13).

Luke’s major purpose, however, was defense of Christianity against the charge that it posed a threat to the order and stability of the Roman Empire. There were, of course, grounds for such suspicions. After all, the founder of the movement had been crucified on a charge of sedition by a Roman procurator, and the movement that claimed his name seemed to evoke tumult, disorder, and riots wherever it spread. Luke’s account met those problems head-on. In the Gospel he presented the trial of Jesus as a serious miscarriage of justice. Pilate had handed Jesus over for crucifixion, but he had found Jesus not guilty. Herod Antipas likewise found no substance in the charges against Jesus (Lk 23:13-16; Acts 13:28). A neutral or even friendly attitude of Roman officials toward leading Christians and the movement as a whole is documented throughout Acts. The Roman proconsul of Cyprus, Sergius Paulus, gladly received Paul and Barnabas and responded positively to their message (Acts 13:7-12). The chief magistrate in Philippi apologized for the illegal beating and imprisonment of Paul and Silas (16:37-39). The proconsul of Achaia, Gallio, found Paul guiltless in the eyes of Roman law (18:12-16). In Ephesus the magistrate intervened in a crowd’s attack on Paul and his companions, rejecting the charges against them (19:35-39). A tribune of the Roman military contingent in Jerusalem arrested Paul, but it turned out that he really saved the apostle from the wrath of a mob; in his letter to the procurator Felix, the tribune acknowledged that Paul was not guilty by Roman law (23:26-29). The same verdict was repeated after Paul’s arraignment before Felix, his successor Festus, and Herod Agrippa II: “This man hasn’t done anything worthy of death or imprisonment” (26:31, NLT). Luke climaxed his story by telling how Paul carried on his missionary activity in Rome, the very heart of the empire, and with the permission of the imperial guards (28:30-31). It is clear throughout Luke’s defense that the strife that attended the beginnings and progress of Christianity was not due primarily to anything within the movement, but rather to Jewish opposition and falsification.

Within his lengthy apology for the integrity of Christianity, Luke’s specific theological perspectives can be clearly seen. The two volume work presents a grand scheme of the history of redemption, extending from the time of Israel (Lk 1–2) through the time of Jesus, and continuing through the time of the church, when the good news for Israel is extended to all nations. Paralleling that emphasis is an insistence that God is present in the redemptive story through the Holy Spirit. In the Gospel, Jesus is presented as the Man of the Spirit; the reality of the Spirit empowered him for his work (Lk 3:22; 4:1, 14, 18). In Acts, the fellowship of Jesus’ disciples is presented as the community of the Spirit (1:8; 2:1-8). What Jesus in the power of the Spirit had begun in his own ministry, the church in the power of the Spirit continues to do.

For Luke, the empowering presence of God’s Spirit was a reality that gave the new faith its power, integrity, and perseverance. It enabled faithful witness (1:8) and created genuine community (2:44-47; 4:32-37), something for which the ancient world desperately longed. The Spirit in the new community produced courage and boldness (see Peter’s defenses in chs 2–5), empowered for service (ch 6), overcame prejudice as in the mission in Samaria (ch 8), broke down walls as in the Cornelius episode (chs 10–11), and sent believers out on missions (ch 13).

The entire story is also punctuated by the centrality of Jesus’ resurrection. Luke, like Paul (see 1 Cor 15:12-21), must have been convinced that without the resurrection of Jesus there would be no Christian faith at all. More than that, the resurrection put God’s stamp of approval on Jesus’ life and ministry, authenticating the truth of his claims. Luke announced his interest in that theme at the outset: the ultimate criterion for an apostolic replacement for Judas was that he must have been, with the other disciples, a witness to Jesus’ resurrection. Throughout Acts, from Peter’s Pentecost sermon and defenses before the Sanhedrin to Paul’s speeches before Felix and Agrippa, the church is shown bearing witness to Jesus’ resurrection as a great reversal executed by God (2:22-24, 36; 3:14-15; 5:30-31; 10:39-42).

Acts falls naturally into two parts, chapters 1–12, and 13–28. The first part, roughly speaking, contains the “acts of Peter.” Part two is largely concerned with the “acts of Paul.” In the first 12 chapters, Peter is the central figure who initiates the choosing of a replacement for Judas Iscariot (ch 1); addresses the multitudes at Pentecost (ch 2); interprets the significance of the healing of a lame man to a temple crowd (ch 3); delivers a defense of the Christian proclamation before the supreme Jewish council (ch 4); leads the apostles in a healing ministry and speaks for them (ch 5); stands in the forefront of conflict with a Samaritan magician, “Simon the Great” (ch 8); launches—though somewhat unwillingly—the movement of the gospel to the Gentiles through Cornelius (chs 10–11); and draws the fire of Herod’s campaign against the church but is miraculously delivered from prison (ch 12).

Proclamation of the gospel to the Gentiles through Paul’s ministry is the theme of part two of Acts (chs 13–28). The story primarily concerns three major missionary tours, each of which moved the gospel into yet untouched territory and expanded earlier missionary efforts. The account of Paul’s life and work climaxes in his arrest in Jerusalem (chs 21–22), a lengthy imprisonment in Caesarea (chs 23–26), and a voyage to Rome (chs 27–28).

Another way of getting at the structure and content of Acts is thematic. It has its starting point in Jesus’ statement, “You shall receive power when the Holy Spirit has come upon you; and you shall be my witnesses in Jerusalem and in all Judea and Samaria and to the ends of the earth” (1:8). Acts can be seen as the story of the fulfillment of that “Great Commission,” unfolding essentially in three stages: (1) witness to Judaism, focused in Jerusalem but also expanding into surrounding Judea and north into Galilee (chs 1–7); (2) witness to Samaria through Philip, Peter, and John (8:1–9:31); (3) witness to the gentile world, first haltingly through Peter (9:32–12:25), and then decisively through Paul (chs 13–28).

See also Luke (Person); Paul, The Apostle; Simon Peter; Theophilus #1; Chronology of the Bible (New Testament).