Open Bible Data Home About News OET Key

A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W XY Z

Tyndale Open Bible Dictionary

Intro ← Index → ©

DAVID

Israel’s most important king. David’s kingdom represented the epitome of Israel’s power and influence during the nation’s OT history.

The two books in the OT devoted to David’s reign are 2 Samuel and 1 Chronicles. His earlier years are recorded in 1 Samuel, beginning at chapter 16. Almost half of the biblical psalms are ascribed to David. His importance extends into the NT, where he is identified as an ancestor of Jesus Christ and forerunner of the messianic king.

Preview

• Early Years

• Preparation for Kingship

• David as King

David’s Lasting Influence

Early Years

Family

David was the youngest son in Jesse’s family, part of Judah’s tribe. The family lived in Bethlehem, about six miles (10 kilometers) south of Jerusalem. His great-grandmother was Ruth, from the land of Moab (Ru 4:18-22). Genealogies in both the OT and the NT trace David’s lineage back to Judah, son of the patriarch Jacob (1 Chr 2:3-15; Mt 1:3-6; Lk 3:31-33).

Training and Talents

Little is known about David’s early life. As a boy, he took care of his father’s sheep, risking his life to kill attacking bears and lions. Later, David publicly acknowledged God’s help and strength in protecting the flocks under his care (1 Sm 17:34-37).

David was an accomplished musician. He had developed his ability as a harpist so well that, when a musician was needed at the royal court of King Saul, someone immediately recommended David.

In Jesse’s family, David was regarded as unimportant. When the nationally known prophet Samuel visited Jesse’s home, all the older sons were on hand to meet him; David was tending the sheep. Samuel had been instructed by God to anoint a king from Jesse’s family, not knowing beforehand which son to anoint. Sensing divine restraint as seven brothers passed before him, he made further inquiry. When he learned that Jesse had one other son, David was immediately summoned. David was anointed by Samuel and endowed with the Spirit of the Lord (1 Sm 16:1-13). Whatever Jesse and his family understood by that anointing, it seems to have made no immediate change in David’s pattern of living. He continued to tend the sheep.

Preparation for Kingship

During his youth, David was willing to serve others, even though he had been anointed king. It was his willingness to take supplies to three of his older brothers in the army that gave him his opportunity for national fame.

As a young man, David was also sensitive toward God. While greeting his brothers on the battlefield, he was disturbed by the Philistine Goliath’s defiance of God’s armies. Although rebuked by his brothers, David accepted the challenge to take on Goliath. He had a reasonable confidence that God, who had helped him encounter a lion and a bear, would aid him against a champion warrior. So, with faith in God and using his ability to sling stones, David killed Goliath (1 Sm 17:12-58).

National Fame

Killing Goliath made David a hero to the nation of Israel. It also brought him into close relationship with the royal family of Saul. But success and national acclaim brought on the jealousy of Saul and ultimately resulted in David’s expulsion from the land of Israel.

In the Royal Court

Saul promised his oldest daughter, Merab, to David in marriage, but then Saul went back on the promise and offered David another daughter, Michal. The dowry of trophies from dead Philistines demanded by Saul was designed to bring about David’s death at Philistine hands. But again David was victorious. Women sang praises of his exploits, intensifying Saul’s jealousy and further endangering David’s life (1 Sm 18:6-30).

In the meantime, David and Saul’s son Jonathan developed a deep friendship. When they made a covenant, Jonathan gave David his choicest military equipment (sword, bow, and belt). Although Saul tried to turn Jonathan against David, the friendship deepened. Because Saul was trying to kill him, David had to flee from the court and live as a fugitive.

After Jonathan had warned David of Saul’s continuing designs on his life, David went to Ramah to see the prophet Samuel. Together they went to Naioth, near Ramah. After sending several groups of men after David, Saul finally went with them himself. All his attempts to seize David were thwarted by the Spirit of God, who caused Saul and his men to prophesy all night in religious fervor (1 Sm 19).

Conferring again with Jonathan, David realized that Saul’s jealousy had developed into hatred. Jonathan, aware that David would be the future king of Israel, requested assurance that his descendants would receive protection under David’s rule (1 Sm 20).

Life as a Fugitive

Fleeing from Saul, David stopped at Nob. By deceiving Ahimelech, who was officiating as priest there, David obtained food supplies and Goliath’s sword (kept as a trophy). An Edomite named Doeg, chief of Saul’s herdsmen, saw what happened at Nob. David continued his flight, taking refuge temporarily in Gath with King Achish (1 Sm 21), then finding shelter in the cave of Adullam, located 10 miles (16.1 kilometers) southwest of Bethlehem. There his relatives and about 400 fighting men joined him. He went to Mizpeh in Moab, appealing to the Moabite king for protection, especially for his parents. When the prophet Gad warned him not to stay there, David moved back to Judah to the Hereth woods (1 Sm 22:1-5).

David’s freedom of movement enraged Saul, who charged his own people with conspiracy. When Doeg reported what he had witnessed at Nob, Saul executed Ahimelech and 84 other priests, then massacred all of Nob’s inhabitants. One priest named Abiathar escaped to report Saul’s atrocities to David, who assured him of protection (1 Sm 22:6-23).

The Philistines were always ready to take advantage of any weakness in Israel. David’s reprisal after a Philistine raid on Keilah, 12 miles (19.3 kilometers) southwest of Bethlehem, gave Saul an opportunity to attack David, who escaped to the wilderness of Ziph, a desert area near Hebron. David and Jonathan met for the last time in that wilderness. Pursued by Saul’s army, David fled still farther south. He was almost encircled in uninhabited country near Maon when Saul had to march his army off to respond to a Philistine attack (1 Sm 23).

At his next place of refuge, En-gedi, on the western shore of the Dead Sea, David was attacked by Saul with 3,000 soldiers. David had an opportunity to kill Saul but refused to harm the “Lord’s anointed” king of Israel. Learning of David’s loyalty, Saul confessed his sin in seeking David’s life (1 Sm 24).

During the years they roamed the wilderness in the Maon/Ziph/En-gedi area, David’s band provided protection for Nabal, a rich man living in Maon with large flocks of sheep at Carmel. In exchange for that protection, David proposed that Nabal share some of his wealth. Nabal’s scorn angered David, but Nabal’s wife, Abigail, appealed to David not to take revenge. When Abigail told Nabal of his narrow escape, he was evidently so shocked that he had a heart seizure. He died ten days later, and Abigail later became David’s wife (1 Sm 25).

Once more Saul came with an army of 3,000 men into the Ziph Desert to find David, and David again passed up an opportunity to harm the king. Finally realizing the folly of seeking David’s life, Saul abandoned pursuit (1 Sm 26).

Refuge in Philistia

David continued to feel unsafe in Saul’s kingdom. Returning to Gath in Philistine country, he was welcomed by King Achish. His followers were allotted the city of Ziklag, where they lived for about 16 months, attracting new recruits from Judah and the rest of Israel (1 Sm 27; 1 Chr 12:19-22).

The Philistine army, marching up to the Megiddo Valley to fight Saul’s army, was uneasy with David’s guerrillas in their rear column, so the commanders put pressure on Achish to dismiss David. When he returned to Ziklag, David found that the city had just been raided by the Amalekites. He pursued the enemy, rescued his people and goods, and divided the spoils with those who had remained behind to guard the supplies (1 Sm 29–30). Meanwhile, the Philistines routed the Israelites at Mt Gilboa, killing Jonathan and two of Saul’s other sons in a fierce battle. Saul, badly wounded, killed himself with his own sword (ch 31).

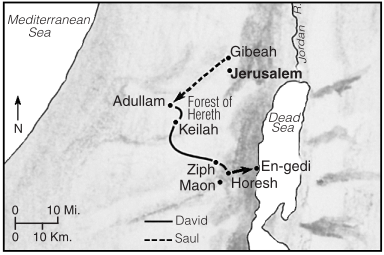

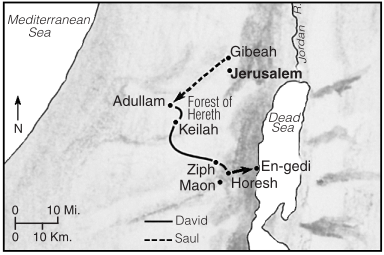

David Flees from Saul

David and his men attacked the Philistines at Keilah from the forest of Hereth. Saul came from Gibeah to attack David, but David escaped into the wilderness of Ziph. At Horesh he met Jonathan, who encouraged him. Then he fled into the wilderness of Maon and into the strongholds of En-gedi.

David as King

David ruled over Israel for about 40 years, although the accounts of his reign do not contain enough information for an exact chronology. He began his rule at Hebron and reigned over Judah’s territory for seven or eight years. With the death of Saul’s successor, Ishbosheth, David was recognized as king by all the tribes and made Jerusalem his capital. During the next decade, he unified Israel through military and economic expansion. Then came approximately 10 years of disruption in the royal family. The last years of David’s reign seem to have been devoted to plans for the Jerusalem temple, which was built in the reign of his son Solomon.

The Years in Hebron

David was subjected to an unusually rugged period of training for his kingship. Serving under Saul, he gained experience in military exploits against the Philistines. Then, during his fugitive wanderings in the desert area of southern Judah, he ingratiated himself with the landholders and sheep raisers by giving them protection. Being recognized as an outlaw of Israel even enabled him to negotiate diplomatic relations with Moab and Philistia.

David was in Philistine country when news came to him that both Saul and Jonathan had been slain. In a beautiful elegy he paid tribute to his friend Jonathan as well as to King Saul (2 Sm 1).

Sure of God’s guidance, David returned to his home, where the leaders of Judah anointed him king at Hebron. He sent a message of commendation to the men of Jabesh for providing a respectable burial for King Saul, probably also bidding for their support.

Confusion probably swept through Israel when Saul was killed, because the Philistines occupied much of the land. Various leaders gathered whatever fighting men they could find, as old tribal loyalties reasserted themselves. David had most of Judah’s tribe firmly behind him.

A kind of civil war broke out between the followers of David and those of Saul, with David gaining the allegiance of more and more people. Saul’s general, Abner, eventually negotiated peace with David, who requested the restoration of Michal as his wife, indicating that he held no animosity toward Saul’s dynasty. With the consent of Saul’s son Ishbosheth, whom Abner had enthroned as king, Abner went to Hebron and pledged Israel’s support for David. But Abner was killed by Joab, one of David’s captains, in a family vendetta, and soon afterward Ishbosheth was assassinated. David publicly mourned Abner’s death and had Ishbosheth’s two murderers executed. Thus, when Saul’s dynasty ended, David was seen by the people not so much as a challenger but as a logical successor. Hence, he was recognized as king by all Israel (2 Sm 2–4).

Consolidation in Jerusalem

When the Israelites turned to David as king, the Philistines became alarmed and attacked (2 Sm 5; 1 Chr 14:8-17). David was strong enough to defeat them and thus unify the people of Israel.

In search of a more central location for his capital, David turned toward the city of Jerusalem, a Jebusite stronghold. Joab responded to his challenge to conquer the city and was rewarded by being made general of David’s army. Jerusalem became known as the “city of David” (1 Chr 11:4-9).

In the same way that he had organized his earliest followers into an effective guerrilla band (1 Chr 11:1–12:22) at Hebron, David began organizing the whole nation (12:23-40). Once established in Jerusalem, he quickly gained recognition from the Phoenicians, contracting for their artisans to build him a magnificent palace in the new capital (14:1-2). He also made sure that Jerusalem would become Israel’s religious center (2 Sm 6; 1 Chr 13–16). His abortive attempt to move the ark of the covenant by oxcart (cf. Nm 4) reminded the powerful king that he still had to do things God’s way to be successful.

With Jerusalem well established as the nation’s capital, David intended to build God a temple. He shared his plan with the prophet Nathan, whose immediate response was positive. That night, however, God sent a message via Nathan that David should not build the temple. David’s throne would be established eternally, the prophet said, and unlike Saul, King David would have a son to succeed him and perpetuate the kingdom; that son would build the temple (2 Sm 7; 1 Chr 17).

Prosperity and Supremacy

Little is recorded about the expansion of David’s rule from the tribal area of Judah to a vast empire stretching from the Nile River of Egypt to regions of the Tigris-Euphrates valley. Nothing in secular history negates the biblical perspective that David had the most powerful kingdom in the heart of that “Fertile Crescent” about 1000 BC.

It is likely that skirmishes with the Philistines to the west were frequent until they finally became subservient to David and paid him tribute. In Saul’s day the Philistines had enjoyed a monopoly on the use of iron (1 Sm 13:19-21). The fact that David freely used iron near the end of his reign (1 Chr 22:3) hints at profound economic changes in Israel.

David’s kingdom expanded southward as he built military garrisons in Edomite territory. Beyond Edom, he controlled the Moabites and Amalekites, who paid him tribute in silver and gold. To the northeast, Israelite domination was extended over the Ammonites and the Arameans, whose capital was Damascus. David’s treatment of both friends and enemies seemed to contribute to the strength of his kingdom (2 Sm 8–10). Although he was a brilliant military strategist who used all the means and resources available to bring Israel success, David was humble enough to glorify God (2 Sm 22; see Ps 18).

Sin in the Royal Family

A lengthy section of the book of 2 Samuel (chs 11–20) gives a remarkably frank account of sin, crime, and rebellion in David’s family. The king’s own imperfections are clearly portrayed; the king of Israel himself could not escape God’s judgement when he did wrong.

Although polygamy was then a Near Eastern status symbol, it was forbidden for a king of Israel (Dt 17:17). David practiced polygamy, however; some of his marriages undoubtedly had political implications (such as his marriages to Saul’s daughter Michal and to princess Maacah of Geshur). Flagrant sins of incest, murder, and rebellion in his family brought David much suffering and almost cost him the throne.

David’s sin of adultery with Bathsheba, committed at the height of his military success and territorial expansion, led him further into evil: he planned a strategy to have Bathsheba’s husband, Uriah, killed on the front line of battle. David seems to have excluded God from consideration in that segment of his personal life. Yet when the prophet Nathan confronted the king with his sins, David acknowledged his guilt. He confessed his sin and pleaded with God for forgiveness (as in Pss 32 and 51). God forgave him, but for nearly ten years David endured the consequences of his lack of self-restraint and his failure to exercise discipline in his family. Although unsurpassed in military and diplomatic strategy, David lacked strength of character in his domestic affairs. Evil fermented in his own house; the father’s self-indulgence was soon reflected in Amnon’s crime of incest, followed by Absalom’s murder of his brother.

Having incurred his father’s disfavor, Absalom took refuge in Geshur with his mother’s people for three years. Joab, David’s general, was eventually able to reconcile David with his alienated son. Absalom, however, having taken advantage of his position in the royal family to gain a following, went to Hebron, staged a surprise rebellion, and proclaimed himself king throughout Israel. His strong following posed such a threat that David fled from Jerusalem. David, still a master strategist, gained time through a ruse to organize his forces and put down his son’s rebellion. Absalom was killed while trying to flee; his death plunged David into grief.

On his return to Jerusalem, David had to work at undoing the damage caused by Absalom’s revolt. His own tribe of Judah, for example, had supported Absalom. Another rebellion, fomented by Sheba of Benjamin’s tribe, had to be suppressed by Joab before the nation could settle down.

David’s Last Years

Although David was not permitted to build the temple in Jerusalem, he made extensive preparations for that project during the last years of his reign. He stockpiled materials and organized the kingdom for efficient use of domestic and foreign labor. He also outlined details for religious worship in the new structure (1 Chr 21–29).

The military and civic organization developed by David was probably patterned after Egyptian practice. The army, rigidly controlled by officers of proven loyalty to the king, included mercenaries. The king also appointed trusted supervisors over farms, livestock, and orchards in various parts of his empire (1 Chr 27:25-31).

David took, or at least began, a census of Israel (2 Sm 24; 1 Chr 21). The incompleteness of the accounts leaves unanswered such questions as the reason for God’s punishment. The king overruled Joab’s objection and insisted that the census be taken. Since David later seemed keenly aware that he had sinned in taking the census, it may be that he was motivated by pride to ascertain his exact military strength (approx. 1.5 million men). God may also have been judging the people for their support of the rebellions of Absalom and Sheba.

Through the prophet Gad, David was given a choice of punishments for his sin. He chose a three-day pestilence. As David and the elders repented, they saw an angel on the threshing floor of the Jebusite Ornan (Araunah). David offered sacrifice there and prayed for his people. Later he purchased the threshing floor, located just outside the city of Jerusalem, concluding that it should be the site for the temple to be built by his son Solomon (1 Chr 21:28–22:1).

David’s Lasting Influence

The Writer of Psalms

The OT book of Psalms became one of the most popular books in ancient Israel, and has remained so among countless millions of people throughout the centuries. These words of praise prepared by David were intended for use in the temple worship (2 Chr 29:30). The 73 psalms ascribed to David generally grew out of his own relationship to God and to other persons.

David probably compiled Book I of the book of Psalms (1–41) and Book IV (90–106), since most of those psalms were written by David himself. Other psalms of his (Pss 51–71) are in Book II (42–72), which was probably compiled by Solomon. As those psalms were used for worship in later generations, various people added others until the time of Ezra.

David’s psalms provided much of the poetry that was set to music for Israel’s worship. His organization of the priests and Levites and his provision of instruments for worship (2 Chr 7:6; 8:14) set the pattern for generations to come in the religious life of Israel.

David in the Writings of the Prophets

David, recognized as the greatest Israelite king, is often mentioned as a standard of comparison in the writings of the OT prophets. Isaiah (as in Is 7:2, 13; 22:22) and Jeremiah often referred to their contemporary kings as belonging to the “house” or “throne” of David. Contrasting David with some of his descendants who did not honor God, both Isaiah and Jeremiah predicted a messianic ruler who would establish justice and righteousness on the throne of David forever (Is 9:7; Jer 33:15). When Isaiah described the coming ruler, he identified him as being from the lineage of Jesse, David’s father (Is 11:1-10). Predicting a period of universal peace, Isaiah saw the capital in “Zion,” identified with the city of David (2:1-4).

Ezekiel promised the restoration of David as king in an eschatological and messianic sense (Ez 37:24-25), and of “my servant David” as Israel’s shepherd (34:23). Hosea likewise identified the future ruler as King David (Hos 3:5). Amos assured the people that God would restore the “tabernacle” of David (Am 9:11) so that they could again dwell in safety. Zechariah referred five times to the “house of David” (in Zec 12–13, rsv), encouraging the hope of a restoration of David’s glorious dynasty. The concept of the eternal throne promised to David during his reign was delineated in the message of the prophets even while they were announcing judgments to come on the rulers and people of their time.

David in the New Testament

David is frequently mentioned by the Gospel writers, who established Jesus’ identity as the “son of David.” The covenant God made with David was that an eternal king would come from David’s family (Mt 1:1; 9:27; 12:23; Mk 10:48; 12:35; Lk 18:38-39; 20:41). According to Mark 11:10 and John 7:42, the Jews of Jesus’ day expected the Messiah (Christ) to be a descendant of David. While stating that Jesus came from the lineage of David, the Gospels also clearly teach that Jesus was the Son of God (Mt 22:41-45; Mk 12:35-37; Lk 20:41-44).

In the book of Acts, David is recognized as the recipient of God’s promises that were fulfilled in Jesus Christ. David is also seen as a prophet whom the Holy Spirit inspired to write the psalms (Acts 1:16; 2:22-36; 4:25; 13:26-39).

In the book of Revelation, Jesus is designated as having the “key of David” (Rv 3:7), and as being “the Lion of the tribe of Judah, the Root of David” (5:5). Jesus is quoted as asserting that “I am the root and the offspring of David, the bright morning star” (22:16).

See also Christology; Chronology of the Bible (Old Testament); Israel, History of; King; Kingdom of God, Kingdom of Heaven; Messiah.

David, A Man of God

David, one of the most gifted and versatile individuals in the OT, is second only to Moses in Israel’s history. He was keenly conscious that God had enabled him to establish a kingdom (Ps 18; cf. 2 Sm 22); it was in that context that he was given the messianic promise of an eternal kingdom.

From David’s own suffering, persecution, and nearness to death came prophetic psalms that portrayed the suffering and death of the Messiah (e.g., Pss 2; 22; 110; 118). Even the hope of the resurrection is expressed in Psalm 16, as the apostle Peter noted on the day of Pentecost (Acts 2:25-28).

Awareness of a vital personal relationship with God is expressed more consistently by David than by any of the faithful men and women who preceded him. He knew that it was not legalistic observance of rules or rituals that made him acceptable to God. Offering and sacrifice could not atone for sin if one had no accompanying contrition and humility. Many of David’s prayers are as appropriate for Christians as they were for God-fearing people in the OT. David’s writings show that “knowing God” was as real in OT times as it was for the apostle Paul, even though the full revelation of God in Jesus Christ was still in the future.