Open Bible Data Home About News OET Key

A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W XY Z

Tyndale Open Bible Dictionary

Intro ← Index → ©

REVELATION, Book of

Last book of the Bible, containing revelations concerning the events of the last days.

Preview

• Author

• Date, Origin, Destination

• Background

• Methods of Interpreting Revelation

• Purpose and Teaching

• Content

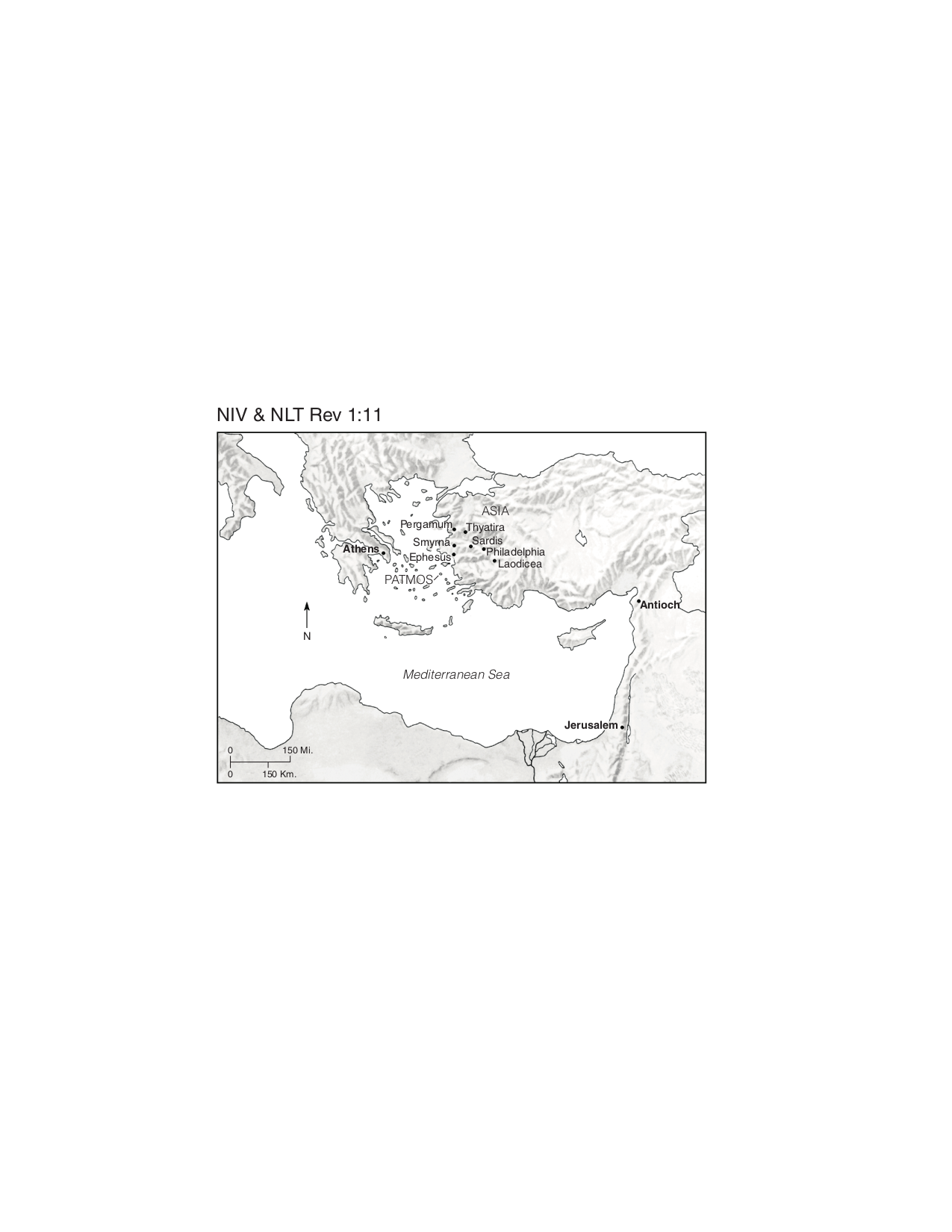

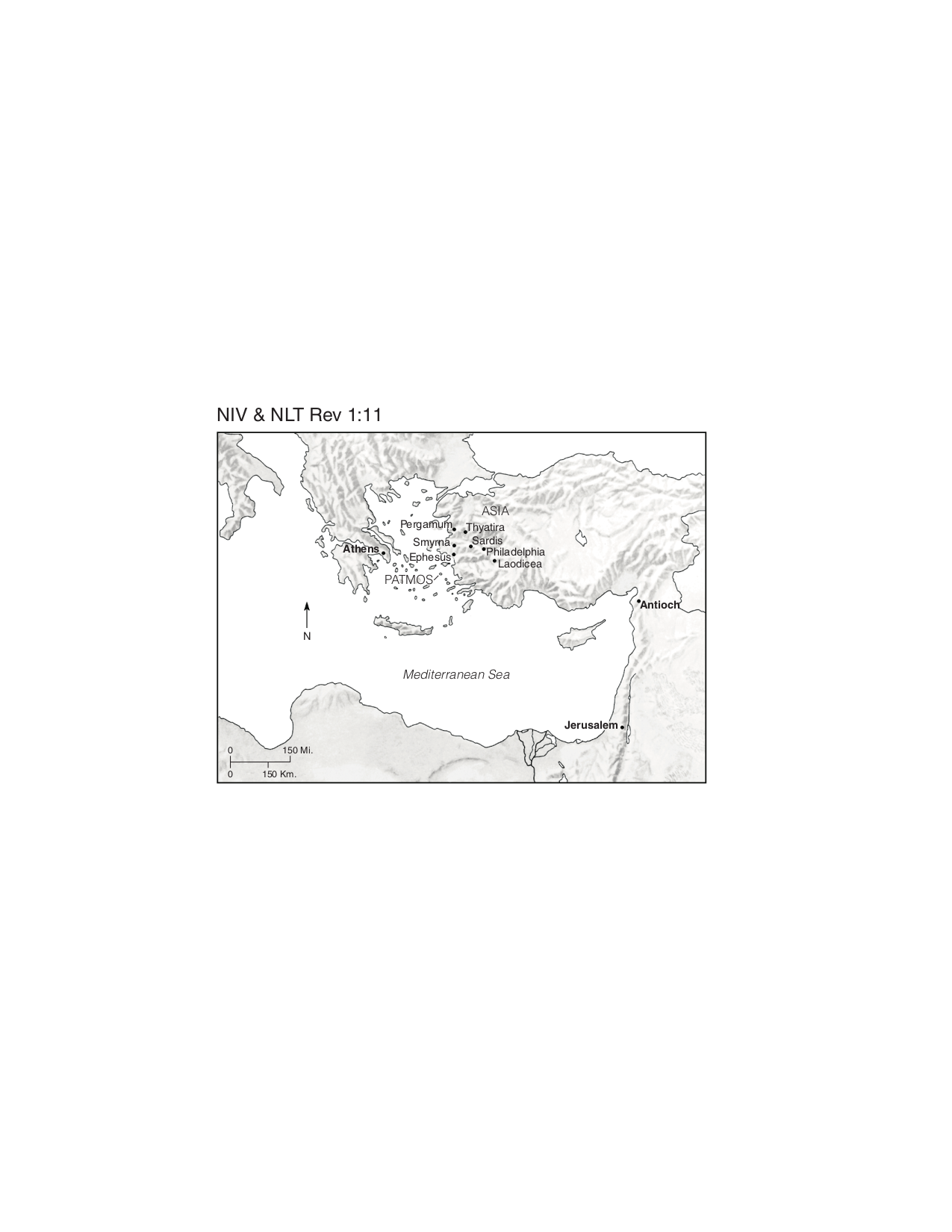

The Seven Churches of Revelation

The seven churches were located on a major Roman road. A letter carrier would leave the island of Patmos (where John was exiled), arriving first at Ephesus. He would travel north to Smyrna and Pergamum, turn southeast to Thyatira, and continue on to Sardis, Philadelphia, and Laodicea—in the exact order in which the letters were dictated.

Author

The earliest witnesses ascribe the authorship of Revelation to John the apostle, the son of Zebedee. Dionysius, the distinguished bishop of Alexandria and student of Origen (early third century), was the first within the church to question its apostolic authorship because it seemed to him that the writing style differed greatly from that found in the fourth Gospel, attributed to John. From the time of Dionysius, the apostolic origin of the book was disputed in the East until Athanasius of Alexandria (c. 350) turned the tide toward its acceptance. In the West, the book was widely accepted and was included in all the principal lists of canonical books from at least the middle of the second century on.

From the internal evidence, the following things can be said about the author with some confidence. He calls himself John (Rv 1:4, 9; 22:8). This is most likely not a pseudonym but rather the name of a person well known among the Asian churches. This John identifies himself as a prophet (1:3; 22:6-10, 18-19) who was in exile because of his prophetic witness (1:9). As such, he speaks to the churches with great authority. His use of the OT and Targums makes it virtually certain that he was a Palestinian Jew, steeped in the ritual of the temple and synagogue. John the apostle fits this profile. The difference between the style of the fourth Gospel and that of Revelation can be explained by the radically different genres of the two books. The Gospel is a composed historical narrative, whereas the book of Revelation is a record of visionary experiences and direct divine revelation. The writer of the Gospel could take his time in crafting a narrative word by word and sentence by sentence. The writer of Revelation was compelled by God to write down immediately whatever he was told or was shown. Thus, the apostle John could easily have been the writer of both. In any event, no convincing argument has been advanced against his authorship.

Date, Origin, Destination

Only two dates for Revelation have received serious support. An early date, shortly after the reign of Nero (AD 54–68), is allegedly supported by references in the book to the persecution of Christians, to the Nero redivivus myth (a revived Nero would be the reincarnation of the evil genius of the whole Roman Empire), to the imperial cult (ch 13), and to the temple (ch 11), which was destroyed in AD 70. The alternate date rests primarily on the early witness of Irenaeus, who stated that the apostle John “saw the revelation . . . at the close of Domitian’s reign” (AD 81–96).

The origin of the book is clearly identified with Patmos, one of the Sporades Islands, located about 37 miles (59.5 kilometers) southwest of Miletus, in the Icarian Sea (1:9). John was apparently exiled on the island due to religious and/or government persecutions arising from his witness to Jesus (1:9).

Likewise, the recipients are clearly the seven historic churches in the Roman province of Asia (modern western Turkey): Ephesus, Smyrna, Pergamum, Thyatira, Sardis, Philadelphia, and Laodicea (1:4, 11; 2:1, 8, 12, 18; 3:1, 7, 14).

Background

The book of Revelation differs from the other NT writings, not in doctrine but in literary genre and subject matter. It is a book of prophecy (1:3; 22:7, 18-19) that contains both warning and consolation—announcements of future judgment and blessing— communicated by means of symbols and visions.

The language and imagery were not as strange to first-century readers as they are today. Therefore, familiarity with the prophetic books of the OT, especially Daniel and Ezekiel, will help the reader grasp the message of the Apocalypse.

While the symbolic and visionary mode of presentation creates ambiguity and frustration for many, it actually lends to the description of unseen realities a poignancy and clarity unattainable by any other method. Such language can trigger a variety of ideas, associations, existential involvement, and mystical responses that the straight prose found in most of the NT cannot achieve.

The letters to the churches indicate that five of the seven were in serious trouble. The major problem seemed to be disloyalty to Christ; this may indicate that the major thrust of Revelation is not sociopolitical but theological. John was more concerned with countering the heresy that was creeping into the churches toward the close of the first century than with addressing the political situation. This heresy seems to have been a type of Gnostic teaching.

Revelation is also commonly viewed as belonging to the group of writings known as apocalyptic literature. The name for this type of literature is derived from the Greek word for “revelation”: apokalupsis. The extrabiblical apocalyptic books were written in the period from 200 BC to AD 200. Although numerous similarities exist, there are also some clear differences.

Much more important than the Jewish apocalyptic sources is the debt John owes to the eschatological teaching of Jesus, such as the Olivet discourse (Mt 24–25; Mk 13; Lk 21). Revelation is unique in its use of the OT. Of the 404 verses of the Apocalypse, 278 contain references to the Jewish Scriptures. John refers frequently to Isaiah, Jeremiah, Ezekiel, and Daniel, and also repeatedly to Exodus, Deuteronomy, and the Psalms. However, he rarely quotes the OT directly.

Methods of Interpreting Revelation

Four traditional ways of understanding Revelation 4–22 have emerged in the history of the church:

Futurist

This view holds that, with the exception of chapters 1–3, all the visions in Revelation relate to a period immediately preceding and following the second advent of Christ at the end of the age. The beasts (chs 13, 17) are identified with the future Antichrist, who will appear at the last moment in world history and will be defeated by Christ in his second coming to judge the world and to establish his earthly millennial kingdom.

Variations of this view were held by the earliest expositors, such as Justin Martyr (d. 164), Irenaeus (d. c. 195), Hippolytus (d. 236), and Victorinus (d. c. 303). This futurist approach has enjoyed a revival since the 19th century and is widely held among evangelicals today.

Historicist

As the word implies, this view sees in Revelation a prophetic survey of history. It originated with Joachim of Floris (d. 1202), a monastic who claimed to have received a special vision that revealed to him God’s plan for the ages. He assigned a day-year value to the 1,260 days of Revelation. In his scheme, the book is a prophecy of the events of Western history from the time of the apostles until Joachim’s own time. In the various schemes that developed as this method was applied to history, one element became common: the Antichrist and Babylon were connected with Rome and the papacy. Later, Luther, Calvin, and other Reformers came to adopt this view.

Preterist

According to this view, Revelation deals with the time of its author; the main contents of chapters are thus viewed as describing events wholly limited to John’s own day. The beasts (ch 13) are identified as imperial Rome and the imperial priesthood. This is the view held by many contemporary scholars.

Idealist

This method of interpreting Revelation sees it as being basically poetic, symbolic, and spiritual in nature. Thus Revelation does not predict any specific historical events at all; on the contrary, it sets forth timeless truths concerning the battle between good and evil that continues throughout the church age. As a system of interpretation, it is more recent than the other three schools.

Purpose and Teaching

NT scholar H. B. Swete wrote of Revelation: “In form it is an epistle, containing an apocalyptic prophecy; in spirit and inner purpose, it is a pastoral.” As a prophet, John was called to separate true from false belief—to expose the failures of the congregations in Asia. He desired to encourage authentic Christian discipleship by explaining Christian suffering and martyrdom in light of the victory over evil won by Jesus’ death and resurrection. John was concerned to show that the martyrs (e.g., Antipas, 2:13) will be vindicated. He disclosed the end both of evil and of those who follow the Beast (19:20-21; 20:10, 15), and he described the ultimate victory of the Lamb and of those who follow him.

Content

The main contents of Revelation are arranged in series of seven items, some explicit, some implied: seven churches (chs 2–3), seven seals (chs 6–7), seven trumpets (chs 8–11), seven bowls (chs 16–18), seven last things (chs 19–22). It is also possible to divide the contents around four key visions: (1) the vision of the Son of Man among the seven churches (chs 1–3); (2) the vision of the seven-sealed scroll, the seven trumpets, and the seven bowls (4:1–19:10); (3) the vision of the return of Christ and the consummation of this age (19:11–20:15); and (4) the vision of the new heaven and new earth (chs 21–22).

John’s Introduction (1:1-8)

The first three chapters of Revelation form a unit and are comparatively easy to understand. They are the most familiar and contain an introduction to the whole book (1:1-8); the first vision, of the Son of Man among the seven lampstands (1:9-20); and the letters or messages to the seven churches in Asia (2:1–3:22).

The first eight verses introduce the whole book. They are freighted with theological content and detail. After a brief preface (1:1-3), John addresses the book to the seven churches of Asia in an expanded ancient letter form (vv 4-8).

The Son of Man among the Lampstands (1:9-20)

After a brief indication of the historical situation that occasioned it (1:9-11), John describes his vision of “someone, like a son of man,” walking among seven golden lampstands (vv 12-16). The person identifies himself as the exalted Lord, Jesus Christ (vv 17-18), and then explains the meaning of the symbolic vision (vv 19-20). Finally, the Lord addresses a rather detailed and specific message to each of the seven churches in Asia (2:1–3:22).

The Letters to the Seven Churches (2:1–3:22)

These seven churches contained typical or representative qualities of both obedience and disobedience that are a constant reminder to all churches throughout every age (cf. 2:7, 11, 17, 29; 3:6, 13, 22; esp. 2:23). Their order (1:11; 2:1–3:22) reflects the natural ancient travel circuit beginning at Ephesus and arriving finally at Laodicea.

Each message generally follows a common literary plan consisting of seven parts:

1. The addressee is given first, following a common pattern in all seven letters: “To the angel of the church in Ephesus, write. . . .”

2. Then the speaker is mentioned. In each case, some part of the great vision of Christ and of his self-identification (1:12-20) is repeated as the speaker identifies himself; for example, “This is the message from the one who holds the seven stars in his right hand, the one who walks among the seven gold lampstands” (2:1; cf. 1:13, 16).

3. Next, the knowledge of the speaker is given. He intimately knows the works of the churches and the reality of their loyalty to him, despite outward appearances. In two cases (Sardis and Laodicea) the assessment proves totally negative. The enemy of Christ’s churches is the deceiver, Satan, who seeks to undermine the churches’ loyalty to Christ (2:10, 24).

4. Following his assessment of the churches’ accomplishments, the speaker pronounces his verdict on their condition in such words as “You do not love me as you did at first” (2:4) or “You are dead” (3:1). Two letters contain no unfavorable verdict (Smyrna, Philadelphia) and two no word of commendation (Sardis, Laodicea). In the letters, all derelictions are viewed as forms of inner betrayals of a prior relation to Christ.

5. To correct or alert each congregation, Jesus issues a penetrating command. These commands further expose the exact nature of the self-deception involved.

6. Each letter contains the general exhortation: “Anyone who is willing to hear should listen to the Spirit and understand what the Spirit is saying to the churches.” The words of the Spirit are the words of Christ (cf. 19:10).

7. Finally, each letter contains a promise of reward to the victor. Each is eschatological and correlates with the last two chapters of the book. Furthermore, the promises are echoes of Genesis 2–3: what was lost by Adam in Eden is more than regained by Christ. We are probably to understand the seven promises as different facets that combine to make up one great promise to believers: wherever Christ is, there the “overcomers” will be.

The Seven-Sealed Scroll (4:1–8:1)

In view of the elaborate use of imagery and visions from 4:1 through the end of Revelation, and in view of the question of how this material relates to chapters 1–3, it is not surprising that commentators differ widely in their treatment of these chapters.

The Throne, the Scroll, and the Lamb (4:1–5:14)

Chapters 4–5 form one vision consisting of two parts: the throne (ch 4) and the Lamb and the scroll (ch 5). Actually, the throne vision (chs 4–5) and the breaking of all seven seals (chs 6–8) form a single, continuous vision and should not be separated; indeed, the throne vision should be viewed as dominating the entire vision of the seven-sealed scroll, and, for that matter, the rest of the book (cf. 22:3).

A new view of God’s majesty and power is disclosed to John so that he can understand the events on earth that relate to the seven-sealed vision (4:1-11; cf. 1 Kgs 22:19). For the first time in Revelation, the reader is introduced to the frequent interchange between heaven and earth found in the remainder of the book. What happens on earth has its inseparable heavenly counterpart.

Chapter 5 is part of the vision that begins with chapter 4 and continues through the opening of the seven seals (Rv 6:1–8:1; cf. introduction to ch 4). The movement of the whole scene focuses on the slain Lamb as he takes the scroll from the hand of the one on the throne. The culminating emphasis is on the worthiness of the Lamb to receive worship because of his death.

Opening of the First Six Seals (6:1-17)

The opening of the seals continues the vision begun in chapters 4 and 5. Now the scene shifts to events on earth. The scroll itself involves the rest of Revelation and has to do with the consummation of the mystery of all things, the goal or end of history for both the overcomers and the worshipers of the beast. The writer tentatively suggests that the seals represent events preparatory to the final consummation. Whether these events come immediately before the end or whether they represent general conditions that will prevail throughout the period preceding the end is a more difficult question.

The seals closely parallel the signs of the approaching end times spoken of by Jesus in his Olivet discourse (Mt 24:1-35; Mk 13:1-37; Lk 21:5-33). This parallel to major parts of Revelation is too striking to be ignored. Thus the seals would correspond to the “beginning of birth pains” in the Olivet discourse. The events are similar to those occurring under the trumpets (Rv 8:2–11:19) and bowls (15:1–16:21) but should not be confused with those late and more severe judgments.

First Interlude: The 144,000 Israelites and the White-Robed Multitude (7:1-17)

The change in tone from the subject matter in the sixth seal, as well as the delay until 8:1 in opening the seventh seal, indicate that chapter 7 is a true interlude. John first sees the angels, who will unleash destruction on the earth, restrained until the 144,000 servants of God from every tribe of Israel are sealed (vv 1-8). Then he sees an innumerable multitude clothed in white standing before the throne of God; these are identified as those who have come out of the great tribulation (vv 9-17).

Some scholars separate the two groups into Jews and Gentiles at large, while others see the two groups as one group viewed from different perspectives.

The Opening of the Seventh Seal (8:1)

After the interlude (ch 7), the final seal is opened and silence for half an hour occurs in heaven to prepare for judgment on earth or to hear the cries of the martyrs on earth (cf. 6:10).

The First Six Trumpets (8:2–11:14)

After a preparatory scene in heaven (8:2-5), the six trumpets are blown in succession (8:6–9:19), followed again by an interlude (10:1–11:14).

The First Six Trumpets (8:6–9:21)

Opinion differs, but it may be best to see the first five seals as preceding the events of the trumpets and bowls. But the sixth seal enters into the period of the outpouring of God’s wrath that is enacted in the trumpet and bowl judgments (6:12-17). The trumpet judgments thus occur during the seventh seal, and the bowl judgments (16:1-21), during the seventh trumpet’s sounding. Therefore, there is some overlapping, but also sequence and advancement, between the seals, trumpets, and bowls.

As in the seals, there is a discernible literary pattern in the unfolding of the trumpets. The first four trumpets are separated from the last three, which are called “woes” (8:13; 9:12; 11:14) and are generally reminiscent of the plagues in the book of Exodus.

The last three trumpets are emphasized and are also called “woes” (8:13) because they are so severe. The first of these involves an unusual plague of locusts (9:1-11) and the second a plague of scorpionlike creatures (vv 13-19). Both of these plagues can best be seen as demonic hordes (cf. vv 1, 11).

The Second Interlude: The Little Book and the Two Witnesses (10:1–11:14)

The major point of chapter 10 seems to be a confirmation of John’s prophetic call, as verse 11 indicates: “You must prophesy again about many peoples, nations, languages and kings” (niv). More specifically, the contents of the little scroll (book) may include chapters 11, 12, and 13.

Chapter 11 is notoriously difficult. It includes a reference to measuring the temple, the altar, and the worshipers, and to the trampling down of the Holy City for 42 months (11:1-2), as well as the description of the two prophet-witnesses who are killed and raised to life (vv 3-13). Opinions vary considerably here; some see this vision as depicting the restored Jewish nation, with the actual prophets Moses and Elijah being revived. Others see the temple as the true church being protected by God during the tribulation and the two witnesses representing the whole faithful church under persecution.

The Seventh Trumpet (11:15–14:20)

The seventh trumpet sounds, and in heaven loud voices proclaim the final triumph of God and Christ over the world. The theme is the kingdom of God and Christ—a dual kingdom, eternal in its duration. The image suggests the transference of the world empire once dominated by a usurping power, now taken by the hand of its true Owner and King. The announcement of the reign of the King is made here, but the final breaking of the enemies’ hold over the world does not occur until the return of Christ (19:11-21).

The Woman and the Dragon (12:1-17)

In this chapter there are three main figures: the woman, the child, and the dragon. There are also three scenes: the birth of the child (vv 1-6), the expulsion of the dragon (vv 7-12), and the dragon’s attack on the woman and her children (vv 13-17).

Since the context indicates that the woman under attack represents a continuous entity from the birth of Christ until at least John’s day or later, her identity in the author’s mind must be the Christian community.

The woman is in the throes of childbirth (v 2). The emphasis is on her pain and suffering, both physical and spiritual. The meaning of her anguish is that the faithful Christian community has been suffering as a prelude to the coming of the Messiah himself and of the new age (Is 26:17; 66:7-8; Mi 4:10; 5:3).

The Two Beasts (13:1-18)

Turning from the inner dynamics of the struggle (ch 12), chapter 13 shifts to the actual earthly instruments of this assault against God’s people—namely, the two dragon-energized beasts. The activities of the two beasts constitute the way the dragon carries out his final attempts to wage war on the offspring of the woman (12:17).

The dragon and the first beast enter into a conspiracy to seduce the whole world into worshiping the beast. The conspirators summon a third figure to their aid—the beast from the earth, who must be sufficiently similar to the Lamb to entice even the followers of Jesus. As the battle progresses, the dragon’s deception becomes more and more subtle. Thus, the readers are called on to discern the criteria that will enable them to separate the lamblike beast from the Lamb himself (cf. 13:11 with 14:1).

The Harvest of the Earth (14:1-20)

The two previous chapters have prepared Christians for the reality that, as the end draws near, they will be harassed and sacrificed like sheep. This section shows that their sacrifice is not meaningless. In chapter 7 the 144,000 were merely sealed; here, however, they are seen as already delivered. When the floods have passed, Mt Zion appears high above the waters; the Lamb is on the throne of glory, surrounded by the triumphant songs of his own; the gracious presence of God fills the universe.

Chapter 14 briefly answers two pressing questions: What becomes of those who refuse to receive the mark of the beast and are killed (vv 1-5)? What happens to the beast and his servants (vv 6-20)?

The Seven Bowls (15:1–19:10)

The series of bowl judgments constitutes the “third woe,” announced in 11:14 as “coming soon” (see comments on 11:14). These last plagues take place “immediately after the distress of those days” referred to by Jesus in the Olivet discourse and may well be the fulfillment of his apocalyptic words: “The sun will be darkened, and the moon will not give its light; the stars will fall from the sky, and the heavenly bodies will be shaken” (Mt 24:29, niv).

Preparation: The Seven Angels with the Seven Last plagues (15:1-8)

Chapter 15 is related to the OT account of the exodus and is strongly suggestive of the liturgical tradition of the ancient synagogue. The chapter has two main visions: the first portrays the victors who have emerged triumphant from the great ordeal (vv 2-4); the second relates the emergence from the heavenly temple of the seven angels clothed in white and gold who hold the seven bowls of the last plagues (vv 5-8).

The Pouring Out of the Bowl Judgments (16:1-21)

These occur in rapid succession with only a brief pause for a dialogue between the third angel and the altar, accentuating the justice of God’s punishments (vv 5-7). This rapid succession is probably due to John’s desire to give a telescopic view of the first six bowls and to hasten then on to the seventh, where the far more interesting judgment on Babylon occurs, concerning which the author will give a detailed account. The final three plagues are social and spiritual in their effect and shift from nature to humanity.

The Prostitute and the Beast (17:1-18)

To a majority of modern interpreters, Babylon represents the city of Rome. The beast stands for the Roman Empire as a whole, including its provinces and peoples. However, it is not sufficient simply to identify Babylon with Rome. For that matter, Babylon cannot be confined to any one historical manifestation, past or future; it has multiple equivalents (cf. 11:8). Babylon is found wherever there is satanic deception. Babylon is better understood here as the archetypal head of all entrenched worldly resistance to God. Babylon is a transhistorical reality that includes idolatrous kingdoms as diverse as Sodom, Egypt, Babylon, Tyre, Nineveh, and Rome. Babylon is an eschatological symbol of satanic deception and power; it is a divine mystery that can never be wholly reducible to empirical earthly institutions. Babylon represents the total culture of the world apart from God, while the divine system is depicted by the New Jerusalem. Rome is simply one manifestation of the total system.

The Fall of Babylon the Great (18:1-24)

Chapter 18 contains the description of the previously announced judgment on the prostitute (17:1). Under the imagery of the destruction of a great commercial city, John describes the final overthrow of the great prostitute, Babylon.

Thanksgiving for the Destruction of Babylon (19:1-5)

In stark contrast to the laments of Babylon’s consorts, the heavenly choirs burst forth in a great liturgy of celebration to God.

The Marriage of the Lamb (19:6-10)

Finally, the cycle of praise is completed with the reverberating sounds of another great multitude (v 6): the redeemed throng (cf. 7:9). They utter the final Hallel in words reminiscent of the great royal psalms (Pss 93:1; 97:1; 99:1).

The Vision of the Return of Christ and the Consummation of the Age (19:11–20:15)

The First and Second Last Things: The Rider on the White Horse and the Destruction of the Beast (19:11-21)

This vision, which depicts the return of Christ and the final overthrow of the beast, may be viewed as the climax of the previous section (vv 1-10) or as the first of a final series of seven last things—namely, the return of Christ; the defeat of the beast; the binding of Satan; the Millennium; the release and final end of Satan; the last judgment; and the new heaven, the new earth, and the new Jerusalem.

Although Satan has been dealt a death blow at the cross (cf. Jn 12:31; 16:11), he nevertheless continues to promulgate evil and deception during this present age (cf. Eph 2:2; 1 Thes 3:5; 1 Pt 5:8-9; Rv 2:10). Yet he is a deposed ruler who is now under the sovereign authority of Christ. Satan is allowed to continue his evil for a short time until God’s purposes are finished. In this scene of the overthrow of the beast, his kings, and their armies, John shows us the ultimate and swift destruction of these evil powers by the King of kings and Lord of lords. They have met their Master in this final and utterly real confrontation (Rv 19:17-21).

The Third and Fourth Last Things: The Binding of Satan and the Millennium (20:1-6)

The Millennium has been called one of the most controversial and intriguing questions of eschatology. The main problem is whether the reference to a Millennium (thousand years) indicates an earthly historical reign of peace that will manifest itself at the close of this present age, or whether the whole passage is symbolic of some present experience of Christians or some future nonhistorical reality. The former view is called premillennial (i.e., Christ’s second coming precedes the Millennium), the latter is amillennial (i.e., there is no literal Millenium).

The binding of Satan removes his deceptive activities from the earth (vv 1-3) during the time the martyred saints are resurrected and rule with Christ (vv 4-6).

The Fifth Last Thing: The Release and Final End of Satan (20:7-10)

In Ezekiel 38–39, “Gog” refers to the prince of a host of pagan invaders from the North, especially the Scythian hordes from the distant land of Magog. In Revelation, however, the names are symbolic of the final enemies of Christ duped by Satan into attacking the community of the saints.

The Sixth Last Thing: The Great White Throne Judgment (20:11-15)

The language of poetic imagery captures the fading character of everything that is of the world (1 Jn 2:15-17). Now the only reality is God seated on the throne of judgment, before whom all must appear (Heb 9:27). His verdict is holy and righteous (expressed symbolically by the white throne). This vision declares that even though it may have seemed that the course of earth’s history ran contrary to his holy will, no single day or hour in the world’s drama has ever detracted from the absolute sovereignty of God.

The Seventh Last Thing: The New Heaven and the New Earth and the New Jerusalem (21:1–22:5)

John here discloses a theology in stone, gold as pure as glass, and color. Archetypal images abound. The church is called the bride (21:2). God gives the thirsty “the springs of the water of life without charge!” (v 6). Completeness is implied in the number 12 and its multiples (vv 12-14, 16-17, 21), and fullness in the cubical shape of the city (v 16). Colorful jewels abound, as do references to light and the glory of God (21:11, 18-21, 23-25; 22:5). There is the “river of the water of life” (22:1) and the “tree of life” (v 2). The “sea” is gone (21:1).

Allusions to the OT abound. Most of John’s imagery in this chapter reflects Isaiah 60 and 65 and Ezekiel 40–48. John weaves Isaiah’s vision of the new Jerusalem together with Ezekiel’s vision of the new temple. The multiple OT promises converging in John’s mind seem to indicate that he viewed the new Jerusalem as the fulfillment of all these strands of prophecy. There are also allusions to Genesis 1–3: the absence of death and suffering, the dwelling of God with his people as in Eden, the tree of life, the removal of the curse. Creation is restored to its pristine character.

The connection of this vision with the promises to the overcomers in the letters to the seven churches (Rv 2–3) is significant. For example, to the overcomers at Ephesus was granted the right to the tree of life (2:7; cf. 22:2); at Thyatira, the right to rule the nations (2:26; cf. 22:5); at Philadelphia, the name of the city of God, the new Jerusalem (3:12; cf. 21:2, 9-27). In a sense, a strand from every major section of the Apocalypse appears in chapters 21–22.

John’s Conclusion (22:6-21)

With consummate artistry, the words of the introduction (1:1-8) are sounded again in the conclusion: the book ends with the voices of the angel, Jesus, the Spirit, the bride, and finally John: “Amen. Come, Lord Jesus” (22:20).

See also Apocalyptic; Daniel, Book of; Eschatology; John, the Apostle.