Jesus’ Miraculous Powers Displayed

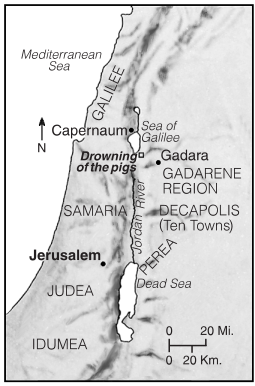

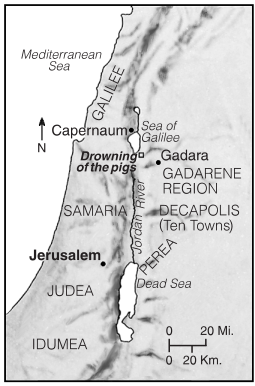

Jesus calmed the storm on the Sea of Galilee, then cast out demons from two men in Gadara.

Open Bible Data Home About News OET Key

OET OET-RV OET-LV ULT UST BSB MSB BLB AICNT OEB WEBBE WMBB NET LSV FBV TCNT T4T LEB BBE Moff JPS Wymth ASV DRA YLT Drby RV SLT Wbstr KJB-1769 KJB-1611 Bshps Gnva Cvdl TNT Wycl SR-GNT UHB BrLXX BrTr Related Topics Parallel Interlinear Reference Dictionary Search

A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W XY Z

MIRACLE

A divine act by which God reveals himself to people. The classical definition of miracle assumes that it is contrary to natural law, but this is a misnomer for two reasons. First, many of the miracles of the Bible used nature rather than bypassed it (e.g., the wind that parted the Red Sea, Ex 14:21). Second, there no longer is a concept of “absolute natural laws”; rather, a phenomenon that is not readily explainable may reflect laws that scientists do not yet fully understand. In Scripture the element of faith is crucial; a natural approach cannot prove or disprove the presence of “miracle.” The timing and content of the process can be miraculous, even though the event may seem natural. The revelatory significance is also important. In every case God performed the miracle not merely as a “wonder” to inspire awe but as a “sign” to draw people to himself.

The Vocabulary of Miracles

In the OT the two main terms are “sign” and “wonder,” which often occur together (e.g., nine times in Dt alone, 4:34; 13:1; etc.). More than one Hebrew term is used for “wonder”—one referring to it as an act of supernatural power and another as being beyond man’s understanding. On the whole, they are used synonymously for God’s providential acts within history. The “sign” refers to an act that occurs as a token or pledge of God’s control over events and as a revelation of God’s presence with his people.

The NT uses the same basic idiom, “signs and wonders,” with the same general thrust (cf. Mt 24:24; Mk 13:22; Jn 4:48; Acts 2:43). A third term is that for “power” or miracle, and this becomes the predominant term in the synoptic Gospels. It signifies the mighty act itself by which God is revealed in Christ. A fourth term is “work,” which along with “sign” is preferred in the Gospel of John. This term is used in John to show that in Jesus the work of the Father is revealed. While the terms are often synonymous (the first three occur together in Rom 15:19-20; 2 Thes 2:9; Heb 2:4), they designate three different aspects of miracles. “Signs” point to the theological meaning of miracle as a revelation of God; “power,” to the force behind the act; “work,” to the person behind it; and “wonder,” to its awesome effect on the observer.

Miracles in the Old Testament

To the Hebrew, a miracle was nothing more nor less than an act of God. Therefore, nature herself was a miracle (Jb 5:9-10; Pss 89:6; 106:2), and an act of kindness or victory over one’s enemies is so described (Gn 24:12-27; 1 Sm 14:23). The natural order is totally under Yahweh’s control, so a miracle was observable not because of its supernatural nature but because of its character as part of the divine revelation. This connection with salvation history is crucial, for Israel at all times tried to guard against a desire for the spectacular. Deuteronomy 13:1-4 warns against accepting a wonder as authenticating a prophet; rather, the authentication must come from the fact that he worships Yahweh.

Miracles in the OT are restricted to critical periods of redemptive history. Many have discussed the act of Creation as the first miracle, but in actuality it is not presented as such in the Genesis account. A miracle is signified by its revelatory significance and/or its connection with crucial points in the history of God’s people—the exodus, the conquest of Jordan, the battle against the insidious Baal worship of the prophetic period. Creation is characterized by one major theme: a chronicle of the beginnings. The miracles of Genesis—striking blind the inhabitants of Sodom, the Flood, Babel—all signify the wrath of God upon those who have turned against him. This is the other side of redemptive history, the judgment of God upon those who are not his people.

The miracles of the exodus account have two foci: The plagues represent the absolute power of Yahweh over the gods of Egypt, and the miracles of the wilderness show God’s absolute care and protection of his people. The plagues are particularly interesting because each one is directed at one of the gods of Egypt and reveals Yahweh as the only potentate. The basic theme is found in Exodus 7:5 and is repeated throughout the account (cf. 7:17; 8:6, 18; 9:14-16, 29; 12:12): “When I show the Egyptians my power and force them to let the Israelites go, they will realize that I am the Lord” (NLT). In this regard they were directed not only at the Egyptians but also to the Israelites, who needed to know that their God would vindicate them against the Egyptians. This is borne out in the major miracle, the crossing of the Red Sea. The plagues themselves show a gradual increase in severity.

The wilderness miracles are intimately connected to the basic theme of the wandering narratives, the trial of Israel in times of desperate need and God’s providential protection of his people when they turn to him. The basic organization of the stories concerns the need itself, which leads to Israel’s complaint; this is followed by Moses’ intercession and then by God’s sovereign intervention. The miracles are interspersed with other stories that tell of God’s punishment when the people’s murmuring tries him too far. The miracle is God’s self-revelation regarding his involvement in the needs of his own; Israel must then respond, and her response determines her blessing or punishment at the hands of Yahweh.

Miracles are conspicuously absent in the period of the united monarchy. This was a time of self-sufficiency, when God worked through the monarchy and did not intervene directly in the life of the nation. The reason is that Israel’s eschatological hopes had been realized and made concrete in the presence of the Holy City and the temple.

It was different during the prophetic period. In the lives of Elijah and Elisha, miracles were predominant. This was a time of apostasy, and under the reign of Ahab and Jezebel the nation turned to paganism and the worship of Baal. The very existence of the Hebraic religion seemed to be threatened, and so the times called for extraordinary measures. Here the wondrous nature of the miracles is more evident than anywhere else in the OT. There are conscious allusions to the exodus miracles, perhaps looking to Elijah as a new Moses reinstituting the true worship of Yahweh. Parallels are seen in the challenge to the priests of Baal (1 Kgs 18; cf. Ex 7); the revelation of God on Mt Horeb with the wind, earthquake, and fire (1 Kgs 19; cf. Ex 19); and the parting of the Jordan (2 Kgs 2:10-14; cf. Ex 14). Many of the miracles were intended to demonstrate the impotence of Baal, such as the drought, the contest on Mt Carmel, and the miraculous sustenance supplied by God. Again, God’s actions within history were part of his self-revelation, the vindication of his messengers, and the punishment of his enemies.

Miracles are infrequent in the writing prophets, perhaps due to the proclamation form of the writings (i.e., they dealt with message rather than deeds). The two major exceptions (apart from the recovery of Hezekiah chronicled in Is 38) are Jonah and Daniel. In Jonah, the miracle is addressed not to the Ninevites but to the Israelites, who are called back to their covenant obligations as the spokesmen for Yahweh. In Daniel the direction is reversed, and the situation is the same as that in Exodus or Kings. The miracles are directed to the Babylonians and Persians and have the same foci as the earlier events of the exodus and Elijah-Elisha chronicles, that is, the supremacy of Yahweh over the foreign gods and the vindication of his messengers. This is the third and final time of crisis and illustrates the major theological use of miracles in the OT.

Miracles in the New Testament

The presence of the miraculous has a similar purpose in the NT; it occurred at a crisis point in salvation history to authenticate the presence of God in historical acts. It differs, however, in that it is transcended by the presence of the very Son of God, who himself is the greatest miracle of all. God now has not only acted in history; he has entered history and has turned it to himself. The parallels with the exodus events are obvious and show that the miracles of Jesus paved the way for the entrance of the new covenant in the same way that the exodus miracles prepared for the old.

Jesus’ Miraculous Powers Displayed

Jesus calmed the storm on the Sea of Galilee, then cast out demons from two men in Gadara.

Jesus’ Understanding

Jesus stressed the connection between his miraculous ministry, especially the casting out of demons (exorcism), and the coming of the kingdom of God. As in the OT, the miracles signify the presence of God, but here it is more direct and also signals the inauguration of his kingdom (Mt 12:28). As such, then, the exorcism miracles mean the binding of Satan and the institution of the reign of God (Mk 3:23-27). At the same time all the miracles signify the dawning of the age of salvation, as expressed in Jesus’ inaugural address at Nazareth (Lk 4:18-21, from Is 61:1-2).

Yet these miracles are not automatic signposts to the act of God; they must be interpreted by faith. Jesus was well aware of the presence of other miracles in his day (Mt 12:27) and so stressed the presence of faith in the healing miracles (Mk 5:32; 10:52). This faith must be directed to the presence of God in the event and in Jesus himself. The necessity of faith also helps to understand Jesus’ refusal to provide his contemporaries with a “sign” (Mk 8:11-12); miracles could never “prove” the presence of God. For a better understanding of the connection between faith and miracles, it is best to note each Evangelist’s individual portrait of the theological use of miracles.

Miracles in Mark

Mark, the first of the four Gospels to be written, has often been called the “action Gospel” because of its emphasis on Jesus’ deeds rather than his teaching. This is also true regarding Jesus’ miracles, for Mark contains more proportionately than any of the others. There are five groups or five kinds of miracles in Mark. The first group centers on Jesus’ authority over demons (Mk 1:21-39). The second concerns Jesus’ authority over the law and conflict with his opponents (1:40–3:6). They result in fame but occasion his refusal to allow his true identity as Son of God to be known. The third group (3:7-30) contains exorcisms and the Beelzebub controversy, centering on his power over Satan. The fourth group (4:35–6:43) contains especially powerful miracles (stilling the storm, the Gaderene demoniac, the raising of Jairus’s daughter) and probably centers on the disciples, as Jesus thereby reveals to them the meaning of the kingdom and seeks to overcome their own spiritual dullness. The fifth and final group (6:30–8:26) continues the theme of the disciples’ misunderstanding and prepares the way for the Passion, with the message regarding the bread, blindness, and the judgment of God.

The miracles in Mark center on conflict, first with Jesus’ opponents and then with his own disciples. While the miracles are harbingers of God’s kingdom, their purpose is to force an encounter with Jesus’ true significance. They do not show Jesus as a Hellenistic wonder worker; in fact, they lead only to amazement and then disbelief in those who do not have faith. Jesus’ personhood has been hidden and can only be understood in light of the cross. The miracles are not proofs but powers; God does not authenticate himself through them but shows himself to those with eyes to see.

Miracles in Matthew

Matthew’s is the teaching Gospel, where dialogue takes precedence over action. Matthew compresses Mark’s narrative in order to make room for didactic material. Therefore, his stress is on the theological implications of faith rather than on the results they contain. Matthew’s groups of miracles are isometric to teaching passages, in keeping with his general practice of combining narrative portions and organizing them around didactic sections. The first group (chs 8–9) combines miracles from Mark’s first, second, and fourth groups and stresses Jesus’ significance as the servant of Yahweh who exercises sovereign power and forgives sins. The secondary theme teaches discipleship and shows the awakening faith of the disciples and their involvement in Jesus’ ministry. The second group (ch 12) centers on his authority over the law (the man with the withered hand) and over Satan (the Beelzebub controversy). The third group (chs 14–15) parallels Mark’s fifth group but has a different purpose. Rather than arousing conflict, the disciples are seen in positive guise, actively involved in the Master’s work. So the disciples become the means by which Jesus’ ministry is continued. Therefore, the disciples are involved as “learners” (the meaning of “disciple”) in his miraculous ministry.

Miracles in Luke

Luke-Acts is remarkable and extremely important because it establishes beyond dispute the early church’s belief that it was in absolute continuity with Jesus and was continuing the work of God in the world. Luke’s major stress is on salvation history, and so one of his major stylistic methods for showing this direct connection is miraculous deeds. Especially enlightening here is Acts 9:32-42, where in two healing miracles Peter duplicated the Lord’s miracles (the paralytic Aeneas, Lk 5:18-26; the raising of Dorcas, Lk 8:49-56).

From this respect also Luke returns to Mark’s interest in the deed more than the teaching. However, Luke goes even further than Mark, for the miracles validate Jesus more directly. The first group follows the inaugural address (4:18-22), which itself presents the miraculous deeds as authenticating signposts to Jesus’ personhood. They center on Jesus’ power and authority (vv 31-41) and validate God’s power in Jesus (5:17; 8:39) as well as faith in Jesus (seen in the “praise” motif, 5:25; 7:16; etc., but especially in Acts 9:35; 13:12; 19:17). The presence of “fear” at the miracles is a human response to having witnessed God’s power (Lk 5:26; 7:16; 8:35-37; 24:5). The call to the disciples occurs in the presence of miracles (5:1-11, at the miraculous catch of fish; vv 27-28, after the healing of the bedridden paralytic).

Therefore, Luke views miracles as having redemptive significance. However, this is not contrary to Mark’s picture. Luke still avoids picturing Jesus as a mere wonder worker; Jesus still refuses to satisfy people’s curiosity for an external sign (Lk 11:29-32; cf. also 9:9), and in the parable of the rich man and Lazarus (16:19-31) he teaches that the unbelieving heart can never be convinced by such events. Nevertheless, they can lead to repentance (10:13-16).

Miracles in John

John is the most directly theological of the Evangelists, and miracles are characteristically given a distinctive Johannine coloring. In the Synoptics, miracles are “acts of power” signifying the entrance of God’s reign into this world via Jesus; thereby, Jesus establishes Satan’s defeat and God’s sovereign control of history. John, however, contains no exorcisms, and the miracles are seen as “signs.” At the same time miracles are part of the larger category of “works” (the other term for miracles used in John), by which Jesus shows the Father’s presence in himself (Jn 10:32, 37-39; 14:10) and they give witness to Jesus as the sent one (5:36; 10:25, 38).

John selects only seven “sign miracles” from many others (20:30) and uses them as part of the thematic development in the respective section of each. For instance, changing the water into wine is a messianic act, signifying the outpouring of the kingdom blessing in the ministry of Jesus, the Messiah (ch 2); the multiplication of the loaves builds upon the “bread of life” and points to the messianic banquet as spiritually present in Jesus (ch 6).

The paradoxical nature of miracles in the Synoptics is even greater in John. He gives more stress to the wondrous nature of the events by providing such details as the stupendous amount of water changed into wine (2:6, approximately 120 gallons, or 454.2 liters); the distance over which Jesus’ healing power works (4:46, almost 20 miles, or 32.2 kilometers); the length of time the man of Bethesda had been lame (5:5, 38 years; cf. 9:1, where the man had been born blind); the amount of bread needed to feed the 5,000 (6:7, where Philip said 200 denarii, or days’ wages, would not have bought enough); and the proof of Lazarus’s death (11:39; he had already begun to decay). John has a great interest in the miraculous. Yet at the same time there is even greater stress on the inadequacy of miracles for faith. The miracles as “signs” have saving value and point to the true significance of Jesus but are related to an awakening faith and in themselves are insufficient (2:11; 4:50). They have christological force, looking to Jesus’ sonship and the Father’s authentication of him but are based on the soteriological decision of the individual. As “signs,” they contain the very presence of God in Jesus, the spiritual reality of the “sight” and “life” he brings (9:35-38; 11:24-26). Yet their purpose is to divide the audience and confront it with the necessity of decision. Two camps result—those seeking understanding and those considering only the outward aspects. Some refuse to consider the signs, and thus they reject them (3:18-21; 11:47-50), while others see them shallowly as mere wonders and fail to see in them the true significance of Jesus (2:23-25; 4:45). On the other hand, some view them with the eye of faith and go on to a realization of his personhood (2:11; 5:36-46; 11:42). In John the highest faith of all is that which does not need external stimulation (20:29).

Miracles in the Rest of the New Testament

Apart from Acts, several passages in the NT speak of the value of miracles. Paul in 2 Corinthians 12:12 and Romans 15:18-19 considered them as “sign-gifts,” which authenticated the divine authority of the “true apostle.” He listed healing and miracles as specific “gifts of the Spirit” in 1 Corinthians 12:9-10. In Galatians 3:5 he considered them evidence for the presence of the Spirit. The author of the letter to the Hebrews in 2:4 said “God bore witness” to the true message of salvation via miracles. Therefore, in the apostolic age the miracles of God’s servants were seen more directly as authenticating signs of God’s action in his messengers.

See also Sign; Spiritual Gifts.