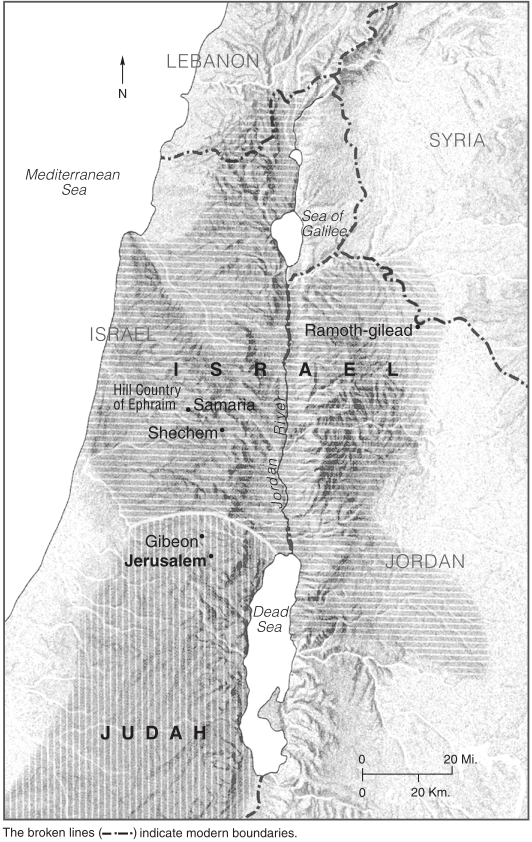

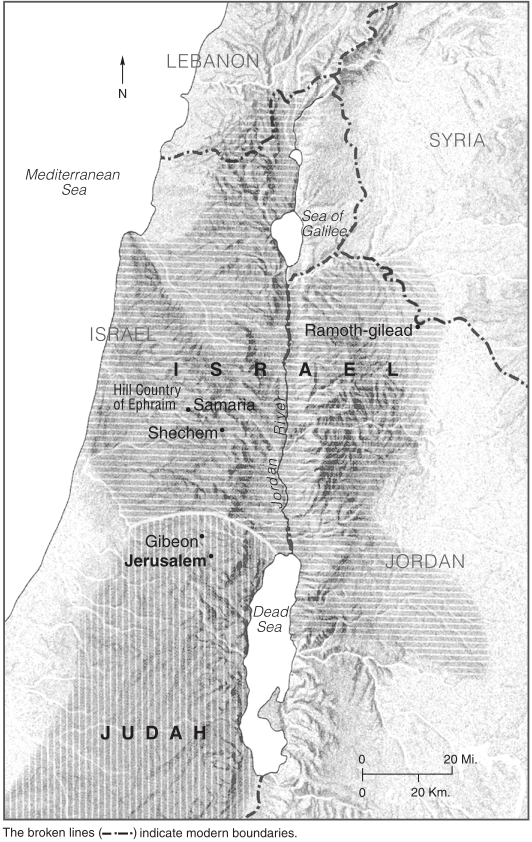

Key Places in 1 and 2 Chronicles

Open Bible Data Home About News OET Key

OET OET-RV OET-LV ULT UST BSB MSB BLB AICNT OEB WEBBE WMBB NET LSV FBV TCNT T4T LEB BBE Moff JPS Wymth ASV DRA YLT Drby RV SLT Wbstr KJB-1769 KJB-1611 Bshps Gnva Cvdl TNT Wycl SR-GNT UHB BrLXX BrTr Related Topics Parallel Interlinear Reference Dictionary Search

A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W XY Z

CHRONICLES, Books of First and Second

Two OT books, historical records of King David and his successors in the land of Judah. The books of Chronicles are among the most neglected books in the Bible, partly because most of the material can be found in Samuel, Kings, or elsewhere in the OT. Fourteen chapters (1 Chr 1–9; 23–27) are little more than lists of names; the rest of the material is primarily historical narrative, which some people find almost as boring as lists. Yet the content of Chronicles is not history in a professional or academic sense because the materials used are comparable to the annals compiled by ancient Near Eastern court scribes. Those sources recorded each year’s most important events and were frequently more propagandistic than objectively historical. The records in Chronicles, somewhat eclectic in nature and ignoring certain facets of national history while emphasizing others, deal with only a selected portion of the history of the Israelites. A good deal of the criticism that the work is historically unreliable has come from lack of understanding the book’s character. Chronicles is not so much a history as a metaphysical interpretation of events in Israelite life in light of covenantal values. It was not sufficient for the Chronicler that kings rose and fell; the events were interpreted from a special religious standpoint.

Preview

• Author

• Date

• Content

Author

In the Hebrew Bible, 1 and 2 Chronicles form a single book. The Bible does not say who wrote that book or when it was written. According to the Jewish Talmud, Ezra wrote “his book and Chronicles—the order of all generations down to himself.” Although many scholars defend the view that Ezra wrote Chronicles, there is still no general agreement about the date and authorship of the book.

The author is usually called “the Chronicler,” a title suggesting that he was a historian. It is possible that he was a scribe, priest, or Levite. Evidently the writer had access to government and temple archives, because repeated references are made to a number of official records of kings (1 Chr 9:1; 27:24; 2 Chr 16:11; 20:34; 25:26; 27:7; 28:26; 32:32; 33:18; 35:27; 36:8) and prophets (1 Chr 29:29; 2 Chr 9:29; 12:15; 13:22; 20:34; 26:22; 32:32; 33:19).

The evidence is suggestive, but not conclusive, that the author of Chronicles also wrote the books of Ezra and Nehemiah. The last two verses of Chronicles are almost the same as the first three verses of Ezra. The language and literary style of all three books are similar. The same theological concerns for the temple and its worship and the same interest in lists and genealogies appear in all three books. In the Hebrew Bible, Ezra-Nehemiah is considered one book and stands before Chronicles. Chronicles stands at the very end of the Hebrew Bible.

Key Places in 1 and 2 Chronicles

Date

It is not possible to determine precisely when the book of Chronicles was written. The book ends with a reference to the decree of Cyrus, king of Persia, permitting the Jewish captives in Babylon to return to their homeland. Since Cyrus’s decree is usually dated about 538 BC, Chronicles could not have been written before that date. But if Ezra-Nehemiah is a part of the same work as Chronicles, the materials could not have been written until Nehemiah returned to Jerusalem in 444 BC.

Genealogies in Chronicles and Ezra-Nehemiah may shed some light on the dating of the books. In 1 Chronicles 3:10-24 the lineage of David and Solomon is traced through the sixth generation after the exile, which would make the date for Anani (the last person in the list) about 400 BC.

The language of Chronicles is definitely that of postexilic Hebrew. The use of the Persian word daric (1 Chr 29:7), plus a lack of any Greek words, places Chronicles in the Persian period (538–331 BC). The word midrash (“exposition”) appears in the OT only in Chronicles (2 Chr 13:22; 24:27) but is very common in postbiblical Hebrew. Around 400 BC is probably the best estimate for the date of Chronicles, based on evidence now available.

Background

During the Persian period, some of the Jews returned to Jerusalem from Babylon soon after Cyrus’s decree. They rebuilt the temple and waited for the messianic age to come. But with drought, economic hardships, and moral and spiritual laxness, their hopes faded. Judah was stable politically as a part of the large, dominant Persian Empire. There was not the slightest possibility of restoring the Davidic kingdom.

If the kingdom of David could not be restored politically, how was a Jew of the early fourth century BC to understand history and the place of the Jews in God’s plan? The Chronicler, living at that time, found the key to history in God’s covenant with David. The first 10 chapters of 1 Chronicles lead up to David; chapters 11–29 detail events of David’s rule. Moses is mentioned in Chronicles 31 times; David, more than 250 times. David planned the temple and collected money to build it. He appointed Levites, singers, and gatekeepers. He divided the priesthood into its orders. He was responsible for the temple worship, which was tremendously important to the Chronicler and his contemporaries.

The Persian period of Israel’s history is largely a silent one, both in other OT materials and in archaeological finds. Of course, all the evidence is not yet in, as archaeologists continue their investigations of the period.

Origin and Purpose

The Chronicler must have lived in Jerusalem and written for the Jewish community there. He refers to Jerusalem about 240 times and to Judah more than 225 times. A negative feeling toward the northern kingdom of Israel can be seen in the almost total lack of references to any northern king. The Chronicler’s attitude toward the north is clearly expressed in the two following verses: “The northern tribes of Israel have refused to be ruled by a descendant of David to this day” (2 Chr 10:19, NLT) and “Don’t you realize that the Lord, the God of Israel, made an unbreakable covenant with David, giving him and his descendants the throne of Israel forever?” (13:5, NLT).

The Chronicler wanted the Jewish people to see that God was sovereign over all things. For example, he includes David’s affirmation: “Yours, O Lord, is the greatness, the power, the glory, the victory, and the majesty. Everything in the heavens and on earth is yours, O Lord, and this is your kingdom. We adore you as the one who is over all things. Riches and honor come from you alone, for you rule over everything. Power and might are in your hand, and it is at your discretion that people are made great and given strength” (1 Chr 29:11-12, NLT).

Compiled in the postexilic period, Chronicles was meant to emphasize the significance of the theocracy seen in light of earlier history. The theocracy was a social configuration God planned for postexilic Judah, a religious rather than secular community. Instead of a king, the Jews had a priesthood of which the Lord approved (as distinct from the corrupt priests who had been to a large extent responsible for the preexilic moral and spiritual collapse of the nation).

The postexilic Judeans were to live as a holy nation, not as people with political and nationalistic ambitions. Therefore, the Chronicler demanded implicit obedience to the Mosaic covenant so that the returning Jews could find prosperity, divine blessing, and grace. The Jews were still the chosen people, purged by the experience of exile, with a new opportunity to fulfill the Sinai covenant.

The Chronicler gave great weight to divine retribution and was insistent that all action be guided by specific moral principles, to reflect God’s character clearly in his people. Because the writer saw God’s hand in all history, punishing the apostate and being gracious to the penitent, he saw in the chastened remnant of the exile the true spiritual heirs of the house of David. He insisted that the postexilic community adhere rigorously to the morality of Sinai, guarding against preexilic apostasy and ensuring divine blessing.

The writer wanted the Jews to know God’s power. He also wanted them to believe in the Lord so that they would be “established.” If they believed God’s messengers, they would succeed (2 Chr 20:20). He also wanted the people to know that Jerusalem was God’s chosen place of worship (2 Chr 5–6), and that the temple, priests, singers, Levites, and gatekeepers had been divinely appointed (1 Chr 28:19). The temple was meant to be a place where all their needs could be met (2 Chr 6:19–7:3).

Content

Chronicles can be briefly outlined as follows: 1 Chronicles—genealogies (1–9); the reign of David (10–29); 2 Chronicles—the reign of Solomon (1–9); the kings of Judah (10:1–36:21); epilogue on the exile and return (36:22-23). Since the Chronicler’s writings do not have a didactic format, the reader must draw out those ideas and principles that are prominent and basic.

One important idea running through Chronicles is the greatness, power, and uniqueness of God. It is expressed most beautifully and forcefully in 1 Chronicles 29:11-12, which declares that everything in heaven and earth belongs to God and he is head over all. Other passages make a similar claim. When Sennacherib, king of Assyria, attacked Judah and Jerusalem, King Hezekiah of Judah admonished his people not to fear the king of Assyria.

Several times the Chronicler repeats the idea that Israel’s God is unique: there is no other God like the Lord. In 1 Chronicles 16:25-26, Psalm 96:4-5 is quoted: “Great is the Lord! He is most worthy of praise! He is to be revered above all gods. The gods of other nations are merely idols, but the Lord made the heavens!” (NLT). Both David and Solomon are quoted as saying that there is no other God but the Lord (1 Chr 17:20; 2 Chr 6:14).

Chronicles emphasizes that the Lord is “greater than all gods” (2 Chr 2:5). The classic passage that stresses the differences between God and the “god” of a nation is in 2 Chronicles 32. When Sennacherib attacked Jerusalem, he asked the people what they were relying on to withstand the siege in Jerusalem. Sennacherib was saying, in effect, “Don’t let Hezekiah deceive you by telling you that your God will deliver you. No god of any nation so far has been able to stand against me. Your God is like the gods of all the other nations. He will not be able to deliver you from me.” The Chronicler observes that the Assyrians spoke of the God of Jerusalem as they spoke of the gods of the peoples of the earth. But God did deliver Hezekiah and the inhabitants of Jerusalem from Sennacherib.

Several passages declare that God rules over the nations (1 Chr 17:21; 2 Chr 20:6). In fact, the Chronicler saw the Lord as the one who directs history. The Lord brought Israel out of Egypt and drove the Canaanites out of their land (1 Chr 17:21; 2 Chr 6:5; 20:7). Some seeming quirks of history are explained with such phrases as “it was ordained by God” (2 Chr 22:7, rsv). Over and over in telling the story of the struggles of the kings of Judah with other nations, Chronicles points out that the Lord always decided the battle (1 Chr 10:13-14; 18:6; 2 Chr 12:2; 13:15; 20:15; 21:11-14; 24:18; 28:1, 5-6, 19).

To the Chronicler the Lord was a covenant-keeping God (2 Chr 6:14). He was the God of justice and righteousness (12:6), so human judges must judge honestly and fairly (19:7). The Chronicler made it clear that no individual or nation could succeed by opposing God (24:20); not only would people fail against God, but they were powerless without him (1 Chr 29:14; 2 Chr 20:12).

The Lord is seen not only as a unique, righteous, and powerful God, but also as a wise God. God tests the human heart and knows when he finds integrity (1 Chr 29:17). Solomon prayed for God to “hear thou from heaven thy dwelling place, and forgive, and render unto every man according unto all his ways, whose heart thou knowest; (for thou only knowest the hearts of the children of men)” (2 Chr 6:30, KJB).

Although God knows all about human beings, and has supreme power in heaven and on earth, men and women are still free to obey or disobey the Lord. The stories in Chronicles depict people who chose to obey or disobey God. Those who obeyed succeeded; but to the extent that others, even kings, disobeyed God, they failed. Three of the Chronicler’s heroes were Jehoshaphat, Hezekiah, and Josiah. Each was a great reformer, and each was commended for obeying the Lord. But each one sinned near the end of his life and incurred the disfavor of God. Jehoshaphat joined an alliance with a wicked king from the north (2 Chr 20:35-37). Hezekiah sinned in receiving envoys from Babylon and “God left him to himself” (32:31). Josiah did not obey the word of God spoken by Pharaoh Neco and was killed (35:21-24).

The Chronicler believed that all human beings have sinned (2 Chr 6:36), and should repent with all their mind and heart (6:38). One of the greatest passages on repentance in all the Bible is in 2 Chronicles 7:14.

A prominent theme in Chronicles is the importance of the temple as the place to meet God in worship. One could say that almost everything in Chronicles is related to the temple in one way or another. For a person living in Jerusalem in the fourth century BC under the domination of the Persians, temple worship was very significant. The Chronicler expressed the importance of true community and institutional worship.

Worship was the dominant attitude of the Chronicler, whose God was worthy to be praised. A worship service is described in 2 Chronicles 29:20-30. Hezekiah commanded a burnt offering and a sin offering to be made for all Israel. The Levites were stationed in the house of the Lord with cymbals, harps, and lyres. The priests had trumpets. “Then Hezekiah ordered that the burnt offering be placed on the altar. As the burnt offering was presented, songs of praise to the Lord were begun, accompanied by the trumpets and other instruments of David, king of Israel. The entire assembly worshiped the Lord as the singers sang and the trumpets blew, until all the burnt offerings were finished. Then the king and everyone with him bowed down in worship. King Hezekiah and the officials ordered the Levites to praise the Lord with the psalms of David and Asaph the seer. So they offered joyous praise and bowed down in worship” (2 Chr 29:27-30, NLT).

See also Chronology of the Bible (Old Testament); Israel, History of; King; Kings, Books of First and Second.

Questioning the Authenticity of the Chronicles

The books of Chronicles, referred to as a single book in this article, have received considerable scholarly criticism about the nature of their content and about apparent discrepancies with material in Samuel and Kings. The differences can be classified as numerical, theological, and historical.

As an example of numerical differences, 1 Chronicles 11:11 says that one of David’s “mighty men” killed 300 men with his spear at one time, but the parallel account in 2 Samuel 23:8 says he killed 800 at one time. Again, 1 Chronicles 18:3-4 says that after defeating King Hadadezer of Zobah, David took from him 1,000 chariots, 7,000 horsemen, and 20,000 foot soldiers; a parallel account in 2 Samuel 8:3-4 says that David took 1,700 horsemen and 20,000 foot soldiers. Although 2 Chronicles 22:2 says that Ahaziah was 42 years old when he began to reign, 2 Kings 8:26 says he was 22; and so on.

Many numbers in Chronicles seem exceptionally high. In 1 Chronicles 21:5, Israel had just over a million men and Judah had 470,000. In another example of a remarkably high number, the temple’s vestibule is said to have been 120 cubits, or approximately 180 feet (54.8 meters), in height (2 Chr 3:4). In 2 Chronicles 13:3, Judah’s army had 400,000 men and Israel’s army 800,000. Some 500,000 of Israel’s army were slain (2 Chr 13:17). In 2 Chronicles 14:9, Zerah the Ethiopian had an army of a million men and 300 chariots.

How should such problems with numbers in Chronicles be understood? First, some of the problems in the text as it now stands may have come about from faulty copying. Also, some excessively high numbers may have been used figuratively to indicate a very large army, or perhaps as estimates. Though not all questions have been answered, scholars have found credible solutions to some of the problems. In the meantime, such matters are seen by evangelical scholars as verifying the human side of the Scriptures without necessarily detracting from their divine origin.

Chronicles also contains some different theological emphases from earlier materials. The best example can be seen by comparing 1 Chronicles 21:1 with 2 Samuel 24:1. In the Samuel account the anger of the Lord was kindled against Israel, and he incited David to harm them by taking a national census. The Chronicler’s account is that “Satan stood up against Israel, and incited David to number Israel.” In one account God moved David to take the census; in the other Satan was the prime mover.

The authenticity of the Chronicler has also been questioned on historical grounds. Several incidents reported in Samuel-Kings are told in a different manner in Chronicles. In 2 Samuel 8:13 David is said to have slain 18,000 Edomites at the Valley of Salt, whereas the Chronicler reports that Abishai, David’s cousin, killed the Edomites (1 Chr 18:12). Again, according to 2 Samuel 21:19, Elhanan slew Goliath the Gittite, whereas the Chronicler says that Elhanan slew Lahmi, the brother of Goliath the Gittite (1 Chr 20:5; most OT scholars today believe that Chronicles preserves the true reading of the original text). A more difficult historical problem is seen by comparing 2 Chronicles 20:35-37 with 1 Kings 22:48-49. The Kings account says that the ships Jehoshaphat, king of Judah, built to bring gold from Ophir were wrecked at Ezion-geber, evidently before they ever left port. When Ahaziah, king of Israel, asked that his servants be allowed to go on the ships with Jehoshaphat’s servants, Jehoshaphat refused. The Chronicler’s version of what happened is different. There Jehoshaphat joined with the wicked Ahaziah in building ships at Ezion-geber to go to Tarshish, but a prophet prophesied that the Lord would destroy the ships because of the alliance with Ahaziah. Both accounts agree that Jehoshaphat built ships at Ezion-geber and that the ships were destroyed before they left port. On the basis of the present status of the texts, however, one cannot tell whether or not Jehoshaphat joined Ahaziah. Whatever happened, the ships were lost.

In a comparison of Chronicles with Kings, a serious problem arises over the war between Asa of Judah and Baasha of Israel. In 2 Chronicles 16:1 one reads that in Asa’s 36th year of reign, Baasha challenged Judah by building a fortress at Ramah. But according to the chronology of 1 Kings 16, Baasha was not even alive in the 36th year of Asa’s reign. First Kings 16:6-8 says that Baasha died and his son Elah succeeded him as king in the 26th year of Asa’s reign.

At one time scholars were quite skeptical about the authenticity of Chronicles. Now they tend to treat Chronicles with respect and appreciation. In some instances new archaeological evidence has tended to support the historicity of the Chronicler’s statement. In other instances reexamination of a discrepancy has shown it to be more apparent than real. If all the facts were known, other problems might also be cleared up to the satisfaction of impartial scholars.