Key Places in 1 Kings

Open Bible Data Home About News OET Key

OET OET-RV OET-LV ULT UST BSB MSB BLB AICNT OEB WEBBE WMBB NET LSV FBV TCNT T4T LEB BBE Moff JPS Wymth ASV DRA YLT Drby RV SLT Wbstr KJB-1769 KJB-1611 Bshps Gnva Cvdl TNT Wycl SR-GNT UHB BrLXX BrTr Related Topics Parallel Interlinear Reference Dictionary Search

A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W XY Z

KINGS, Books of First and Second

Books continuing the history of the covenant people as recorded in Joshua, Judges, and the books of Samuel. The record in Kings begins with the events at the end of David’s reign (1 Kgs 1–2). It continues through the reign of Solomon (chs 3–11); the histories of the divided kingdoms (1 Kgs 12—2 Kgs 17); and the history of the surviving kingdom in the south, through its fall in 586 BC and the subsequent kindness shown Jehoiachin by Evil-merodach, king of Babylon, around 561 BC (2 Kgs 18–25).

Preview

• Sources

• Content

Authorship and Date

Kings was originally regarded as one book in the Hebrew canon; the division into two books of approximately equal length appeared first in the Septuagint and finally entered the Hebrew Bible in the 15th century AD.

The book itself is anonymous, and information about its author can only be deduced by examining the concerns and perspectives of the work. The Babylonian Talmud (Baba Bathra 15a) attributes Kings to Jeremiah. Although this identification could have arisen from the tendency of later Jewish tradition to assign biblical books to prophetic authors, the theory of origin in prophetic circles fits the evidence quite well. Substantial portions are given to the lives of the prophets; 16 of 47 chapters are devoted to the lives of Elijah and Elisha (1 Kgs 17—2 Kgs 10), and there is considerable interest in other prophetic figures such as Ahijah (1 Kgs 11:29-39; 14:1-16), an unnamed man of God (13:1-10), and Micaiah (22:13-28). Possible dependence on Isaiah (2 Kgs 18–20; cf. Is 36–39) and Jeremiah (2 Kgs 24–25; cf. Jer 52) also suggest prophetic origin. The author-compiler also shows intense concern with the efficacy of the prophetic word, frequently calling attention to the fulfillment of words spoken earlier by the prophets.

One might initially think that such a history would be unlikely for a prophet, but the evidence is to the contrary. The prophets were the guardians of the covenant relationship and are known to have produced accounts used as sources by other biblical historians. The following are among such sources: the acts of Samuel the seer, the acts of Nathan the prophet, the acts of Gad the seer (1 Chr 29:29); the acts of Nathan the prophet, the prophecy of Ahijah the Shilonite, the visions of Iddo the seer (2 Chr 9:29); the chronicles of Shemaiah the prophet and of Iddo the seer (12:15); the annotations of the prophet Iddo (13:22); and the acts of Uzziah by Isaiah the prophet (26:22). Add to this the fact that Kings is positioned in the Hebrew canon in the Former Prophets (Joshua to 2 Kings), and a consistent picture of prophetic origin emerges.

The date of the final part of the book must be after the last events recorded. Evil-merodach’s kindness toward Jehoiachin (c. 561 BC) is the terminus of the book and therefore fixes the earliest date. Since the work shows no knowledge of the restoration period, a date before 539 BC is probable. The author’s selection of his data to answer the burning theological questions of the exilic community also suggests a date between 561 and 539 BC.

Sources

The compiler of Kings specifically names three of the sources that he used in his work, and biblical scholars have suggested the presence of a number of other sources that may have been cited. Of course, the sources not mentioned specifically by the compiler are only the speculations of those who have studied his work and can have only varying degrees of probability. The sources both specified and alleged are as follows.

The Book of the Acts of Solomon

As 1 Kings 11:41 says, “The rest of the events in Solomon’s reign, including his wisdom, are recorded in The Book of the Acts of Solomon” (NLT). Presumably additional materials of a biographical nature were included, specifically accounts similar to the judgment between the two mothers (3:16-28) or the visit of the queen of Sheba (10:1-10). There has been debate as to whether these materials were official court records or nonofficial documents. Some scholars have attempted to isolate further materials within this section by identifying descriptions of the buildings as from temple archives (chs 6–7) and lists of administrators as from administrative documents (chs 4–5), but this must remain speculative.

The Book of the History of the Kings of Israel

This source is mentioned 17 times in Kings, usually in the closing formulas at the end of the account of the reign of a northern king. Some idea of the nature of these chronicles can be derived from looking at the type of information to which the compiler refers his readers (see 1 Kgs 14:19; 16:27; 22:39; 2 Kgs 13:12; 14:28). These passages suggest that this source was the official annals covering the reigns of the kings.

The Book of the History of the Kings of Judah

This source is mentioned in 15 passages, and as with the kings of Israel, is found in the concluding formulas to the accounts of the reigns. This source was to be consulted for additional details on individuals’ reigns (for example, see 1 Kgs 15:23; 22:45; 2 Kgs 20:20; 21:17). These sources for the histories of the two kingdoms were probably similar to the annals known from the surrounding cultures, particularly from the reigns of Assyrian kings. They were likely official court histories kept in Samaria and Jerusalem.

In addition to these explicitly mentioned sources, scholars have suggested the compiler drew on other sources that he does not name.

Davidic Court History

Second Samuel 9–20 is often identified as a unit of material in the composition of the books of Samuel; it is variously called “the court history” or “the succession narrative.” Because of similar vocabulary and outlook, 1 Kings 1–2 are often associated with this material from Samuel. The statement of 1 Kings 2:46, “so the kingdom was now firmly in Solomon’s grip,” is taken to be the end of this record.

Sources for the House of Ahab

The reigns of individual kings are ordinarily given only brief notices; for example, the father of Ahab, Omri, is given eight verses, even though when judged by political and economic significance, he was among the greatest of the northern kings (1 Kgs 16:21-28). However, beginning with the reign of Ahab, the record becomes quite expansive, and extensive coverage is given the dynasty of Ahab through the coup by Jehu (1 Kgs 16—2 Kgs 12). The use of the stereotyped formulas for the reigns is suspended in this material, and the existence of other literature used by the compiler is probable. This material is commonly subdivided into further sources for the lives of Elijah and Elisha and the reign of Ahab.

The Elijah section covers material in the following chapters: 1 Kings 17–19, including the feeding by the ravens, the incidents with the widow of Zarephath, the drought, the fire on Carmel, and the revelation of God at Sinai; 1 Kings 21, the affair of Naboth’s vineyard; and 2 Kings 1, the death of Ahaziah’s messengers. The reign of Ahab, which gets so much attention in Kings, is primarily a backdrop for the accounts concerning Elijah.

The Elisha material found in 2 Kings 2–13 may have had an independent literary development from that of the Elijah accounts. It includes the following: chapter 2 (Elisha’s succession to the prophetic office, the purification of a spring, the death of mocking children); chapter 3 (on the campaign against Moab); chapter 4 (the widow’s oil, the Shunammite woman); chapter 5 (Naaman’s leprosy); chapter 6 (the Aramean attempt to capture Elisha); chapter 7 (the famine in Samaria); chapter 8 (the Shunammite’s property, the coup of Hazael); chapter 9 (the anointing of Jehu); and chapter 13 (the death of Elisha). No other portion of the OT takes the sheer delight in the miraculous that is seen in the Elisha narratives.

In 1 Kings 16 to 2 Kings 13 there are additional incidents not directly related to the biographies of Elijah and Elisha; accounts such as the military campaigns of 1 Kings 20:1-34 and further details of Jehu’s coup (2 Kgs 9:11–10:36) are often attributed to a third source containing accounts of the dynasty of Ahab and his successors. In all three of these possible sources the orientation is toward affairs in the northern kingdom.

Isaiah Source

The account of the reign of Hezekiah contains a section (2 Kgs 18:13–20:19) that is nearly a verbatim citation of material also found in Isaiah (Is 36:1–39:8). The section records the invasion of Sennacherib, the mission of the Rabshakeh, Hezekiah’s prayer, Isaiah’s prophecy, Hezekiah’s illness, the regression of the sun, and the envoys from Merodach-baladan. The material must be regarded as based on the book of Isaiah or some other source used in both Isaiah and Kings.

A Prophetic Source

Because Kings shows great interest in the prophets and their ministries, various scholars have suggested that yet another source was used by the compiler; this would be an independent literary unit containing accounts of the prophets. This source would have contained the records for the material on Ahijah (1 Kgs 11:29-39; 14:1-16), unnamed prophets (ch 12; 20:35-43), Micaiah (22:13-28), and other references.

Apart from the sources explicitly mentioned and inferences about their character, the remainder of the sources suggested have only varying degrees of probability. Considerable scholarly effort has gone into identifying and characterizing such sources, but it remains speculative. When considering the sources the compiler may have used, one important caution must be kept in mind. Even if such sources did exist, one cannot have confidence in a reconstruction of the compositional history. Which sources had already been integrated into a larger composition before they were used by the compiler of Kings? We cannot be certain that the life situation out of which these other sources grew has been correctly identified, nor can we know that even the compiler himself was aware of the past history of his sources. Biblical scholarship has expended considerable energy in trying to delineate the past history of the book of Kings, but it has often been at the neglect of the unity of perspective that is the product of the final compiler(s) in whose hands the book received its canonical form.

What is important to understanding the book is not the perspective of its various sources (of which the compiler himself may have been unaware), but the perspective of the book as a whole on the history of the kingdoms. It is the outline that the compiler has imposed on the sources that establishes the teaching of the book; his sources are used in accord with his own purposes, a fact that makes the purposes for which the sources had been prepared largely irrelevant to the teaching of the book in its present form. Exploring possible sources, worthwhile in itself, must not eclipse the message of the book as a whole. This is not to imply that the books of Kings are simply a compilation of unaltered sources. The writer(s) undoubtedly exercised a measure of selectivity and literary skill in composing the historical narrative.

One compositional technique of the compiler is quite prominent in the histories of the divided kingdoms: this is the use of formulaic introductions and conclusions to the various reigns. The formulas for both kingdoms are quite similar, differing only in minor details. For the kings of Judah, the full introductory formula is as follows: (1) year of accession synchronized with the regnal year of the northern king; (2) age of the king at his accession; (3) length of his reign; (4) name of his mother; (5) judgment on the character of the reign. The account of a Judean king’s reign is concluded as follows: (1) a reference to the chronicles of the kings of Judah for further information; (2) a statement regarding the death of the king, including the place of burial; (3) successor: “And his son reigned in his stead” (rsv). The full formula for a Judean king can be seen, for example, in the reign of Rehoboam (1 Kgs 14:21-22, 29-31).

The formulas differ slightly for the kings of Israel; the introduction is as follows: (1) year of succession synchronized with the regnal year of the southern king; (2) length of his reign; (3) location of the royal residence; (4) condemnation for idolatry; (5) name of the king’s father. The account of an Israelite king’s reign ends as follows: (1) a reference to the chronicles of the kings of Israel for further information; (2) a statement regarding his death; (3) a statement of the succession of his son, unless a usurper follows. The full formula for an Israelite king can be seen, for example, in the reign of Baasha (1 Kgs 15:33-34; 16:5-6).

There is some variation in the use of these patterns, but on the whole, they are consistently followed and provide the basic framework for the history of the divided kingdom. The synchronisms of the reigns provide data for constructing the chronology of the period. The variations in the formulas may reflect the characteristics of the sources the compiler was using or may reflect his own interests. The name of the mother of a Judean king is recorded, but not of an Israelite king, perhaps reflecting concern with a more exact and fuller record of the Davidic succession. The royal residence is presumed to be Jerusalem for the southern kings (though it may be mentioned) but is recorded for the northern kings since it moved several times, from Shechem to Penuel to Tirzah to Samaria. The mention of the king’s father for a northern ruler also reflects the frequent change in dynasties there, as opposed to the dynastic stability of Judah, which is reinforced by mentioning the burial of almost all its kings in the city of David.

Theology and Purpose

The books of Kings record the history of the covenant people from the end of the reign of David (961 BC) through the fall of the southern kingdom (586 BC). Yet it is not history written in accord with modern expectations for history textbooks. Rather than concentrating on economic, political, and military themes as they shaped the history of the period, the compiler of Kings is motivated by theological concerns.

Evaluation of the theology and purpose of the books of Kings is made easier by the fact that there is a parallel history for much of Kings found in the books of Chronicles. By comparing the two accounts, especially where the later Chronicler adds or deletes material found in Kings, the interests of both histories are thrown into clearer relief.

The books of Kings were composed during the exile, likely between 560 and 539 BC. Jerusalem had been turned into rubble, and there was no longer a throne of David. Those two pillars of the popular theology—the inviolability of the temple and the throne of David (Jer 7:4; 13:13-14; 22:1-9; see 1 Kgs 8:16, 29)—had tumbled. If Israel’s faith was to survive, the burning questions that had to be answered were “How did it all happen? Can’t God keep his promises to David and to Zion? Have the promises failed?” The writer of Kings aims to deal with the bewilderment of the chosen people in response to the disasters of 722 BC (fall of Samaria) and 586 BC (fall of Jerusalem). Kings, like the book of Job, is a theodicy, a justification of the ways of God to men.

In order to answer the question “How did it happen?” the compiler adopts the procedure of recounting the history of the covenant people in light of standards propounded in the Law. For this reason Kings could be called Pentateuchal history, or even more pointedly, Deuteronomic history, for standards propounded only in the book of Deuteronomy in the Pentateuch are used by the compiler to measure the kingdoms. Among the prominent themes selected from Deuteronomy and applied to the kingdoms are the centralization of worship, the institution of the monarchy, the efficacy of the prophetic word, and the outworking of the covenant curses on disobedience.

Centralization of Worship

The primary concern of the writer is the purity of the worship of the Lord. His major criterion for measuring this purity is the attitude of the kings toward centralization of worship in the Jerusalem temple as opposed to the worship of the Lord elsewhere and the continuation of Canaanite cults mingled with Yahwism at the high places. Centralization of worship at the central shrine is called for in Deuteronomy 12. Perhaps “centralization of worship” is a misnomer, for worship was always centered around the tabernacle in the periods prior to the temple; the change that is envisaged in Deuteronomy is not the centralizing of worship but rather the fact that the shrine would no longer be mobile but stationary. For the kings of the northern kingdom, this criterion becomes virtually a stereotyped formula that “he did that which was evil in the sight of the Lord and walked in the way of Jeroboam son of Nebat, who sinned and made all Israel sin along with him” (see 1 Kgs 14:16; 15:30; 16:31; 2 Kgs 3:3; 10:31; 13:2, 11; 14:24; 15:9, 18, 24, 28; 17:22). The compiler of Kings sees the rival altars with the golden calves at Dan and Bethel as the great sin of which the northern kings never repented (1 Kgs 12:25–13:34). Rejecting the primacy of Jerusalem, these altars became the rod with which to measure the northern kings. All the kings of Israel are condemned by this standard (except for Shallum, who reigned but a month, and Hoshea, the last of the northern kings)—even Zimri, the murderer of Elah, who ruled only one week before committing suicide in the flames of his own palace (16:9-20). For the kings of Judah, a different standard is used: what their attitude was to the high places where heterodox worship was allowed to flourish in the environs of Jerusalem. Only Hezekiah and Josiah receive the compiler’s unqualified endorsement for following the ways of David (2 Kgs 18:3; 22:2). Six others are commended for their zeal in suppressing idolatry, though they did not remove the high places (Asa, 1 Kgs 15:9-15; Jehoshaphat, 22:43; Jehoash, 2 Kgs 12:2-3; Amaziah, 14:3-4; Azariah, 15:3-4; Jotham, 15:34-35). The remainder of the Judean kings are condemned for their participation in the high places and their desecration of the temple itself. This one theme is the preeminent motif in the book.

History of the Monarchy

A second prominent interest for the compiler was to trace the history of the monarchy. Deuteronomy 17:14-20 provides for the day when Israel would ask for a king and charges that king with the basic religious responsibility for the people. This provision for a king, again a feature found only in Deuteronomy, becomes the basis for the compiler’s intense interest in the history of the monarchy, and particularly the religious fidelity of the kings. David becomes the model of the ideal king, the one by whom the others are measured, the one whose sons “continue long in his kingdom in the midst of Israel” (17:20; see also 1 Kgs 15:11; 2 Kgs 18:3; 22:2 for following in the ways of David, and 1 Kgs 14:8; 15:3-5; 2 Kgs 14:3; 16:2 for the reverse). The compiler wanted to show that God had been faithful to David even though David’s sons were not faithful. While both kingdoms had about the same number of kings, the northern kingdom is marked by repeated dynastic changes and regicide through its 200 years, while the dynasty of David is maintained as a lamp in the south through 350 years (1 Kgs 11:13, 32, 36; 15:4-5; 2 Kgs 8:19; 19:34; 20:6). It is the disaster that had befallen the house of David, and the consequent doubts about the promises of God, that prompted the compiler to write.

Efficacy of the Prophetic Word

Another reason why Kings can be called Deuteronomic history is its concern with the efficacy of the prophetic word. There are three passages in the Pentateuch that deal with the institution of the prophetic order: Numbers 12:1-8; Deuteronomy 13:1-5; and Deuteronomy 18:14-22. It is only in Deuteronomy 18 that the test of a true prophet is given: that what he has spoken comes about, that his words are fulfilled. Notice the number of instances where the writer calls attention to the fulfillment of the words of the prophets: 2 Samuel 7:13 in 1 Kings 8:20; 1 Kings 11:29-36 in 12:15; 1 Kings 13:1-3 in 2 Kings 23:16-18; 1 Kings 14:6-12 in 14:17-18 and 15:29; 1 Kings 16:1-4 in 16:7, 11-12; Joshua 6:26 in 1 Kings 16:34; 1 Kings 22:17 in 22:35-38; 1 Kings 21:21-29 in 2 Kings 9:7-10, 30-37 and 10:10-11, 30; 2 Kings 1:6 in 1:17; 2 Kings 21:10-15 in 24:2; 2 Kings 22:15-20 in 23:30. The writer is concerned to show that the words of the prophets were efficacious, powerful words. His concern with the prophetic order is also seen in the material devoted to Elijah and Elisha and to other prophetic figures.

Fulfillment of the Curses

Another aspect of the compiler’s interest in Deuteronomy is seen in his concern to trace the fulfillment of the covenant curses on disobedience. God’s covenant with Israel would issue in curses or blessings depending on the obedience of the people; the compiler of Kings sees the curses inflicted on the two kingdoms because of their failure to meet the demands of the covenant. He takes care to show that most of the curses of Deuteronomy 28:15-68 had some historical realization in the life of the people. Moses had warned that disobedience would “bring a nation against you from afar, from the end of the earth, as the eagle swoops down” (Dt 28:49, nasb), and the Assyrians came to Samaria and the Babylonians to Jerusalem (28:52). The siege of Samaria lasted from 724 to 722 BC, and the siege of Jerusalem from 588 to 586 BC. The dire conditions of the siege would drive the people to devouring their own children; women would feed on their afterbirths. It happened to Israel in the siege of Ben-hadad (2 Kgs 6:24-30). Just as the Lord had delighted to prosper and multiply his people, so he would not refrain from destroying them and scattering them among the peoples of the earth (Dt 28:63-67).

In these and other ways the writer of Kings set out to write the history of Israel and Judah to solve a theological dilemma. How was one to reconcile the exile with God’s promises to the nation and David? His answer is twofold: (1) the problem was not with God but with the people’s disobedience—God remains just; (2) the end of the state does not equal the end of the people or the house of David. Here the ending of the book is instructive: Evil-merodach releases Jehoiachin from prison, elevates him above the other kings, and provides his rations (2 Kgs 25:27-30). Even during the exile, though cut down to almost nothing, the house of David still enjoys the favor and blessing of God. God has not abandoned his promises; the people should keep hope.

Other themes in Kings also show the theological motivations underlying the compiler’s selection and arrangement of the data, particularly his use of Deuteronomy as a framework for examining the history of the people. Compare the laws governing the observance of Passover in Exodus 12:1-20 and Deuteronomy 16:1-8: whereas the Passover is centered in the family in Exodus, it is celebrated at the sanctuary in Deuteronomy. The writer of Kings is careful to show that the Passover during the reign of Josiah was celebrated in accordance with the requirements of Deuteronomy (2 Kgs 23:21-23). A passage in Deuteronomy is explicitly cited with reference to Amaziah’s keeping the law (Dt 24:16 in 2 Kgs 14:6).

Contrast with Chronicles

The interests of Kings are further highlighted when compared with the parallel accounts in Chronicles. While the writer of Kings worked in the aftermath of the destruction of Jerusalem and had to answer the “how?” and “why?” questions, the Chronicler is part of the restoration community. Here the burning theological questions were not “how?” and “why?” but rather “What continuity do we have with David? Is God still interested in us?” The need is not to account for the exile but rather to relate the postexilic and the preexilic. The building of the second temple and the ordering of worship there show up in increased detail in Chronicles in any matter pertaining to the former temple. Chronicles is a history of Judah and of the Davidic line, reflecting the fact that it alone survives after the exile. Interesting, too, are the things omitted from the account by the Chronicler. Since he is not building a case for an indictment, as was done in Samuel and Kings, he is free to omit references to David’s sin with Bathsheba (2 Sm 11) or to Solomon’s difficulties in gaining the throne (1 Kgs 1–2). Since in his day the northern kingdom had not survived, the Chronicler did not go into detail about the sins of Jeroboam (chs 13–14). Chronicles is interested more in the affairs of the temple and does not show the marked interest in prophetic matters found in Kings, so that the lives of Elijah and Elisha are omitted (1 Kgs 16—2 Kgs 10). Nor does the Chronicler recite the sins that led to the demise of the northern kingdom (2 Kgs 17:1–18:12). In all these examples one can see the interplay of the historical moment and theological concerns of the people and the compilers. Each compiler has selected and arranged the data in accordance with the concerns and needs of the community in which he was a member; comparing the two accounts throws the interests of each into sharp relief.

Content

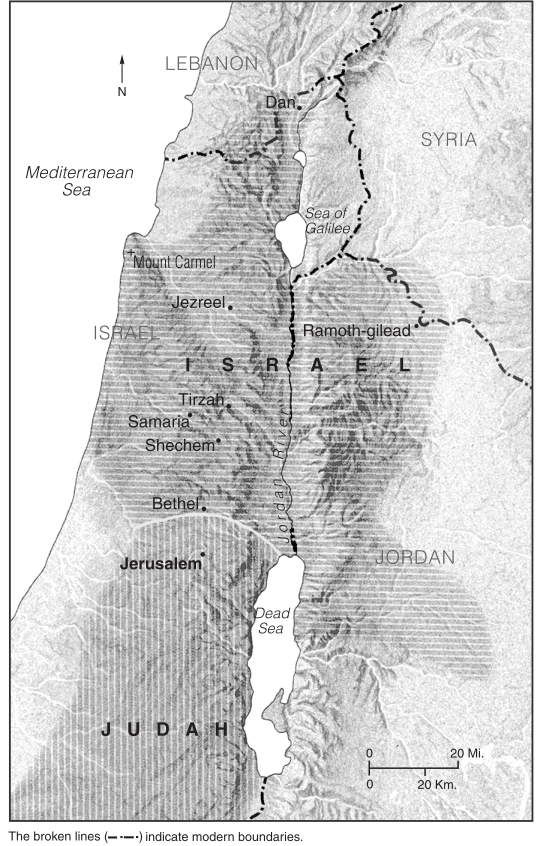

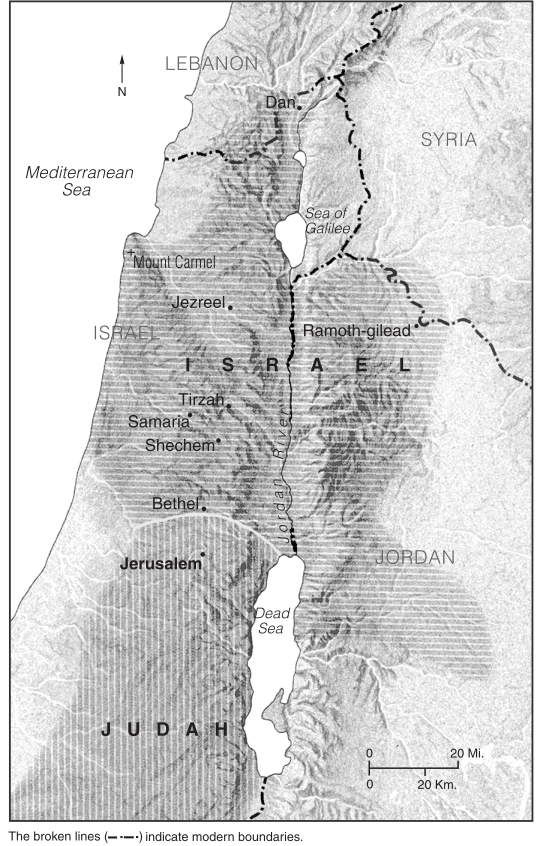

Key Places in 1 Kings

The books of Kings fall into three parts: (1) the reign of Solomon (1 Kgs 1–11); (2) the history of the divided kingdom (1 Kgs 12–2 Kgs 17); (3) the history of the surviving kingdom in Judah (2 Kgs 18–25).

The Reign of Solomon (1 Kgs 1–11)

The record begins with an account of the court intrigue surrounding Solomon’s accession to the throne, set against the backdrop of the abortive coup by Adonijah (ch 1). The dying David charges Solomon to obey the commandments of God (2:1-4) and also to take vengeance on his enemies (vv 5-9). After David’s death Solomon orders the deaths of Adonijah, Joab, and Shimei, and the banishment of Abiathar, the priest who had supported Adonijah in his bid for the throne (vv 13-46). Enemies eliminated, the kingdom was firmly established by Solomon (v 46).

The remainder of Solomon’s reign is divided into two parts: Solomon the good, who follows in the ways of his father, David (chs 3–10); and Solomon the bad, whose heart is led astray (ch 11). While sacrificing at Gibeon, Solomon asks God to give him the gift of wisdom to rule—wisdom promptly demonstrated in the quarrel of two prostitutes about a child (ch 3). An account is given of the administrative organization of the kingdom and the incomparable wisdom of Solomon (ch 4). The compiler of Kings gives extensive coverage to the preparations (ch 5), building (chs 6–7), and dedication (ch 8) of the temple. God appeared to Solomon a second time, reminding him to keep his commandments as David had done (9:1-9). Details are given of the king’s building and commercial activities (vv 10-27). The account of the visit by the queen of Sheba is followed with elaboration of Solomon’s splendor (ch 10). But Solomon did not keep God’s commands; seduced to pagan worship by his foreign wives, he was not fully devoted to the Lord as David had been (11:4), and God determined to take away the northern tribes from the rule of his son (vv 11-13). As punishment from the hand of God, Solomon faced rebellion among conquered peoples (vv 14-25) and within Israel in the person of Jeroboam (vv 26-40).

History of the Divided Kingdom (1 Kgs 12—2 Kgs 17)

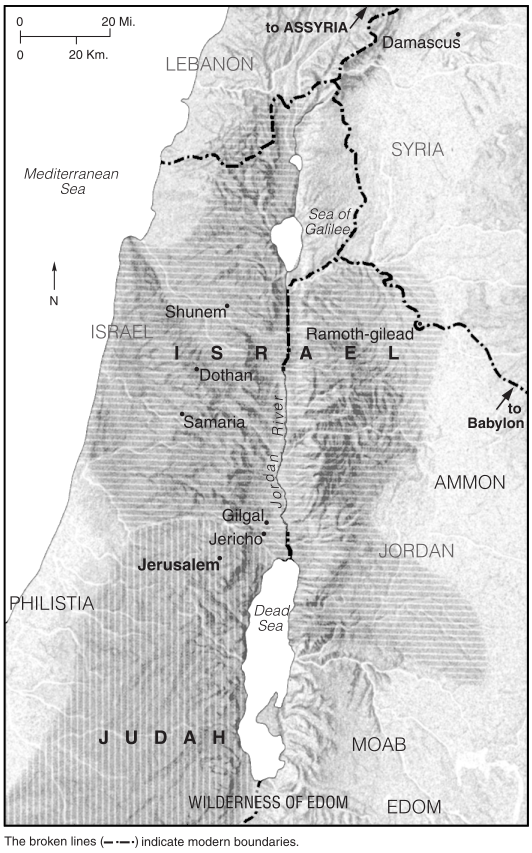

Key Places in 2 Kings

The united monarchy dissolved after the death of Solomon. The northern kingdom (Israel) would exist for about two centuries, would be ruled by 20 kings from nine different dynasties, and would show a history of internal weakness riddled with regicide and usurpation. In contrast, the southern kingdom would last for three and a half centuries and would be ruled by 19 kings of Davidic descent (apart from a short period under the dynastic interloper Athaliah).

There had been a long history of independent action and even warfare between the northern and southern tribes prior to David and Solomon, so it is no surprise that the division would take place along the lines that it did. The immediate cause, however, was the unwise severity with which Rehoboam replied to the representatives of the northern tribes while negotiating for the kingship. Jeroboam, the popular hero of the earlier insurrection against Solomon, became king in the north. He immediately erected the rival sanctuaries at Dan and Bethel (1 Kgs 12); these rival altars became the measure by which the kings of Israel were condemned for following in the sins of Jeroboam.

For two generations there would be warfare between Israel and Judah over the border areas in Benjamin claimed by both sides. Fifty years of sporadic fighting on their mutual frontier, interlaced with invasions from the Arameans in the north or the Egyptians in the south, would consume the reigns of Jeroboam, Nadab, Baasha, Elah, and Zimri in Israel and of Rehoboam, Abijam, and Asa in Judah (1 Kgs 13:1–16:20).

The accession of Omri in Israel introduced a ruling house that would last for a total of four generations and end the dynastic instability of the northern kingdom. Though Kings gives Omri a scant eight verses (1 Kgs 16:21-28), he was among the greatest of the northern kings, forging alliances with the Phoenicians and Judah; for over a century, the Assyrians would call Israel “the house of Omri.”

The reigns of Omri’s successors, Ahab, Ahaziah, and Jehoram, are treated at disproportionate length, taking almost a third of the total book, 16 of 47 chapters (1 Kgs 17—2 Kgs 10). This is due to the fact that the compiler of Kings incorporated extensive coverage of the lives of Elijah and Elisha, weaving a contrast between good and evil by paralleling the dynasty of Omri with these prophets. Ahab and Jezebel were used as foils for the account of Elijah, so that Ahab became a paradigm of the evil king (e.g., 2 Kgs 21:3).

Because of this preoccupation with the dynasty of Omri and the lives of Elijah and Elisha, the equivalent period in Judah is not given as extensive coverage. During this period, the northern kingdom appears to have exercised some hegemony over Judah, as attested by the marriage of an Omride (Athaliah, 2 Kgs 8:18, 26) to Jehoram of Judah and the subservient role of Jehoshaphat to Ahab at the battle of Ramoth-gilead (1 Kgs 22). Judah’s fortunes declined in this period when Edom revolted against Jehoram (2 Kgs 8:20-22), costing Judah control over the port at Ezion-geber and consequent economic losses.

In 842 BC Jehu, after being anointed king by a prophet (2 Kgs 9:1-13), led a coup ending the house of Omri and also killing Ahaziah of Judah (vv 14-29). Jehu’s purge also brought the death of Jezebel, Ahab’s family, members of the family of Ahaziah, and the ministers of Baal (9:30–10:36). The consequences were severe politically: the murder of the Phoenician princess Jezebel and the king of Judah cost Israel its allies to the north and south.

Jehu’s dynasty had the longest succession of any in Israel, including Jehoahaz, Jehoash, Jeroboam II, and Zechariah, a period spanning 90 years. Jehu’s murder of Ahaziah of Judah set the stage for the one threat to the continuity of the Davidic dynasty. Queen Athaliah, herself an Omride, seized the throne and attempted a purge of Davidic pretenders. She ruled for six years, until the faithful priest Jehoiada staged a countercoup to place the child Joash on the throne of David (ch 11).

Israel endured a half century of weakness as a result of Jehu’s coup, during which the Arameans had a free hand, reducing the forces of Jehu’s son Jehoahaz to a small army and bodyguard (2 Kgs 13:1-7).

The reemergence of Assyria early in the ninth century BC gave relief to Israel and Judah. Assyrian armies conquered the Arameans; with that threat removed, Israel and Judah enjoyed a dramatic resurgence. Jehoash of Israel, grandson of Jehu, reconquered cities lost to the Arameans (2 Kgs 13:25); Elisha died during his reign (v 20). In the south Amaziah reconquered the Edomites (14:7). Amaziah and Jehoash renewed the warfare between the kingdoms, with the north again victorious (vv 8-14).

Under Jeroboam II, Israel enjoyed a period of prosperity when the borders of the kingdom reached the same extent as they had under Solomon (2 Kgs 14:23-28). Uzziah (Azariah), his contemporary in Judah, also fortified Jerusalem and undertook a program of offensive operations extending Judah’s sway to the south (14:21-22; 15:1-7).

Yet this resurgence was but a brilliant sunset in the history of the two kingdoms. After the death of Jeroboam II, the history is one of successive disasters, culminating in the fall of Israel and the subjugation of Judah to the might of Assyria. The next 30 years in Israel would see four dynasties, three represented by only one king, and repeated regicides as the northern kingdom hastened to its demise. A period of civil war and anarchy would see five kings in just over ten years (2 Kgs 15). Heavy tribute was paid to Tiglath-pileser III in both the north and south (15:19-20; 16:7-10). Israel and the Arameans forged a coalition to throw back the Assyrians and sought to press Ahaz of Judah into the fight; Ahaz appealed to Tiglath-pileser III for help. The coalition was destroyed, and Israel and Judah became vassals. Hoshea defected as soon as he felt safe, looking to Egypt for help, but it was suicide for the northern kingdom. Shalmaneser V retaliated, and the political history of the state of Israel came to an end (17:1-23). The area was resettled with other displaced populations (vv 24-41).

Israel had faced the Arameans and survived, only to fall to Assyria. And now, similarly, Judah would outlast Assyria, only to fall to Babylon.

History of the Surviving Kingdom of Judah (2 Kgs 18–25)

Ahaz’s appeal for Assyrian aid cost him his liberty, and Judah became a vassal of the Assyrian Empire. Illegitimate worship flourished under his rule (2 Kgs 16:1-19). Ahaz was succeeded by the first of the outstanding reform kings of Judah: Hezekiah. Much of the account of his reign is given to his rebellion against Sennacherib of Assyria: the rebellion, the Assyrian envoys and threats, Isaiah’s assurances of deliverance, and the destruction of the Assyrian armies (18:9–19:37). Hezekiah’s illness was averted after a sign and oracle from Isaiah (20:1-11). As part of what appears to be negotiations toward an anti-Assyrian alliance, Hezekiah also entertained envoys from Babylon, a decision that the prophet announced would be costly (vv 12-21).

Hezekiah was followed by Manasseh, who ruled longer than any other king of Judah (a total of 55 years). His reign was marked by great apostasy—apostasy so severe that the compiler of Kings regarded his reign as sufficient reason for the exile that was unavoidable (2 Kgs 21:1-18; cf. 23:26; 24:3-4; Jer 15:1-4). Manasseh was followed by his son Amon, a carbon copy of his father, who ruled only two years before he was deposed by the people (2 Kings 21:19-26).

The second great reform king of Judah, Josiah, followed. In his reign the Book of the Law was found while the temple was being refurbished; he led the people in a renewal of the covenant and suppressed illegitimate worship (2 Kgs 22:1–23:14). The Assyrian Empire was in rapid decline, so Josiah extended his borders to the north, destroying the altar at Bethel and the high places throughout Samaria (23:15-20). A great Passover celebration was convened in Jerusalem, and further measures were taken to rectify worship (vv 21-25). Josiah tried to block Pharaoh Neco’s foray to assist Assyria, and he lost his life at Megiddo (vv 26-30).

Josiah was the only king of Judah to have three of his sons succeed him. At his death the people put Jehoahaz on the throne, but Neco removed him three months later and took him to Egypt in chains (2 Kgs 23:31-33), replacing him with another son of Josiah, Eliakim, whose name was changed to Jehoiakim (vv 34-37). During his reign, Nebuchadnezzar conquered Judah, and Jehoiakim became his vassal. Late in his life Jehoiakim rebelled against Nebuchadnezzar. Jehoiakim died, leaving his son Jehoiachin to face retaliation from Babylon (24:1-10). Nebuchadnezzar besieged Jerusalem; when the city fell, Jehoiachin, the queen mother, the army, and the leaders of the land were carried away captive. Nebuchadnezzar put Mattaniah (uncle of Jehoiachin and third son of Josiah) on the throne, changing his name to Zedekiah (vv 11-17). Nine years later Zedekiah, too, would rebel against Babylon. Nebuchadnezzar besieged the city for two years and, when it fell, utterly destroyed it. Zedekiah’s sons were killed before his eyes, and then his own eyes were put out, and he was taken to Babylon (24:18–25:21). Nebuchadnezzar appointed Gedaliah to rule as governor from nearby Mizpah; he was assassinated, and the conspirators fled to Egypt (25:22-26).

The book concludes by showing that God had not forgotten his promise to David, mentioning that in captivity Jehoiachin enjoyed favor from the hand of Evil-merodach, successor of Nebuchadnezzar (2 Kgs 25:27-30).

See also Chronicles, Books of First and Second.