Moses Leads the Israelites to Mount Sinai

Open Bible Data Home About News OET Key

OET OET-RV OET-LV ULT UST BSB MSB BLB AICNT OEB WEBBE WMBB NET LSV FBV TCNT T4T LEB BBE Moff JPS Wymth ASV DRA YLT Drby RV SLT Wbstr KJB-1769 KJB-1611 Bshps Gnva Cvdl TNT Wycl SR-GNT UHB BrLXX BrTr Related Topics Parallel Interlinear Reference Dictionary Search

A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W XY Z

MOSES

Great leader of the Hebrew people who brought them out of bondage in Egypt to the Promised Land in Canaan; also the one who gave them the law at Mt Sinai that became the basis for their religious faith through the centuries. Focused in this one person are the figures of prophet, priest, lawgiver, judge, intercessor, shepherd, miracle worker, and founder of a nation.

The meaning of his name is uncertain. It has been explained as a Hebrew word meaning “to draw out” (Ex 2:10; cf. 2 Sm 22:17; Ps 18:16). If, however, it is an Egyptian name given him by the daughter of Pharaoh who found him, it is more likely from an Egyptian word for “son” (also found as part of many well-known Egyptian names such as Ahmose, Thutmose, and Ramses). No one else in the OT bears this name.

Without question, the greatest figure in the OT (mentioned by name 767 times), his influence also extends to the pages of the NT (where he is mentioned 79 times). The first 40 years of his life were spent in the household of Pharaoh (Acts 7:23), where he was instructed in all the wisdom of the Egyptians. The next 40 years he spent in Midian as a fugitive from the wrath of Pharaoh, after killing an Egyptian who was mistreating a Hebrew. His last 40 years were devoted to leading the Israelites out of bondage in Egypt to the land God had promised to Abraham and his descendants (Gn 12:1-3). He died at the age of 120 after leading the Israelites successfully through 40 years of wandering in the wilderness to the very edge of the Promised Land on the east side of the Jordan River (Dt 34:7). He is one of the great figures in all of history, a man who took a group of slaves and, under inconceivably difficult circumstances, molded them into a nation that has influenced and altered the entire course of history.

Preview

• The Second 40 Years—In Midian

• The Third 40 Years—From Egypt to Canaan

Background

The only source of information for the life of Moses is the Bible. Archaeology confirms the credibility of the events associated with Moses, but it has never provided any specific confirmation of his existence or work. His story begins with the arrival in Egypt of Jacob, his sons, and their families during a time of famine in Canaan. Invited by Joseph and welcomed by Pharaoh, the family settled down in northeast Egypt in an area known as Goshen, where they remained for 430 years (Ex 12:40). With the passing of time, their numbers grew rapidly, so that the land was filled with them (1:7). A new king arose over Egypt who did not know Joseph. The biblical account does not give the name of this pharaoh, and there has never been agreement as to his identity. He has most frequently been identified as Thutmose III (1504–1451 BC), Seti I (1304–1290 BC), or Ramses II (1290–1224 BC). Out of fear that their growing numbers might become a threat to the security of his nation, Pharaoh determined to take measures to reduce their number. He put them to work building the store cities of Pithom and Rameses, but the severity of the work did not diminish them. He next tried to enlist the cooperation of the midwives to destroy the male babies, but they would not carry out his orders. He then ordered his own people to drown the male infants in the Nile River. Against the background of this first-known Jewish persecution, the baby Moses was born.

The First 40 Years—In Egypt

Birth and Early Life

A man of the family of Levi named Amram married his father’s sister Jochebed (Ex 6:20; cf. 2:1). Their first son, Aaron, three years older than Moses, was born before the command to drown the Hebrew babies was given, as there is no indication that his life was in danger. However, the cruel order was in force when Moses was born, and after three months, when his mother could no longer hide him, she took a basket made of bulrushes and daubed it with bitumen and pitch. She put the baby into the basket and placed it among the reeds along the banks of the river. An older sister, Miriam, stayed near the river to see what would happen. Soon the daughter of Pharaoh (identified by Josephus as Thermuthis and by others as Hatshepsut, but whose actual identity cannot be determined) came to the river to bathe, as was her custom. She discovered the baby, recognized it as one of the Hebrew children, and determined that she would raise the child as her own. Miriam emerged from her hiding place and offered to secure a Hebrew woman to nurse the child, an arrangement that was agreeable to the princess. Miriam took the baby to his own mother, who kept him for perhaps two or three years (cf. 1 Sm 1:19-24). Nothing is recorded of those formative years. Whether his mother continued seeing him during his later childhood and young manhood or revealed his true identity to him or taught him the Hebrew faith are matters of speculation. Moses was instructed in all the wisdom of the Egyptians, as would befit a member of the royal household, and he became mighty in his words and deeds (Acts 7:22).

Identification with His Own People

Just when Moses became aware that he was a Hebrew rather than Egyptian cannot be known, but it is clear that he knew it by the time he was 40 years old. One day he went out to visit his people and to observe their treatment, for the cruel measures taken against them by Pharaoh at the time of Moses’ birth had not been lifted. Seeing an Egyptian beating a Hebrew, Moses in great anger killed the Egyptian and buried him. He thought the deed had gone unnoticed until the next day when he encountered two Hebrews fighting with each other. When he tried to act as peacemaker, they both turned on him and accused him of murder: “Who made you a prince and a judge over us? Do you mean to kill me, as you killed the Egyptian?” (Ex 2:14, rsv). Acts 7:25 adds: “He supposed that his brethren understood that God was giving them deliverance by his hand” (rsv). Aware that being a member of Pharaoh’s household would not exempt him from punishment now that the deed was known, Moses fled for his life to the land of Midian.

The Second 40 Years—In Midian

Marriage into the Family of Jethro

Soon after arriving in Midian, Moses sat down by a well, where he observed the seven daughters of the priest of Midian who had come to the well to draw water for their father’s flock. Shepherds came and drove them away, but Moses intervened and helped them water their animals. When Jethro (Ex 3:1; also called Reuel, 2:18; Hobab, Nm 10:29) learned what had happened, he invited Moses to stay with his family and gave him Zipporah as his wife. (There is some disagreement among scholars regarding the identity of Hobab in Numbers 10:29; some think he was Moses’ father-in-law, while others maintain that Hobab was Moses’ brother-in-law. See also Hobab). Two children, Gershom (Ex 2:22) and Eliezer (18:4), were born to Moses and Zipporah during the years in Midian. Forty years passed, and Moses’ thoughts about his former life in Egypt must have faded into the past. He could not have foreseen that God would soon thrust him back into the midst of the court in Egypt, where he would confront the son of the now-dead pharaoh with the demand to release the Hebrew people from the bondage they had endured for so many years. God had not forgotten his people and was now ready to deliver them.

Encounter with God at the Burning Bush

One day, while Moses was taking care of the flocks of his father-in-law, he led them to Mt Horeb (known also as Sinai), where God appeared to him in a flame of fire out of the midst of a bush that burned but was not consumed. Moses approached to observe the strange sight more closely and heard God speak to him out of the bush, “Moses, Moses!” Moses replied, “Here am I.” Before he could come any nearer to the bush, God said, “Do not come near; put off your shoes from your feet, for the place on which you are standing is holy ground” (Ex 3:4-5, rsv). He further identified himself as the God of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob. He assured Moses that he was aware of the cruel afflictions of his people and had heard their cries. Then he told of his plan to send Moses to Egypt to deliver his people from their bondage.

Faced with a challenge that seemed beyond his capabilities, the aged Moses began making excuses for not accepting the task. God assured Moses that he would be with him (Ex 3:11-12). To his excuse that he would not be able to give an answer if the people asked him the name of the God he represented, God revealed his name in the cryptic statement, “ ‘I Am the One Who Always Is’ . . . Just tell them, ‘I Am has sent me to you’ ” (vv 13-14, NLT). Many interpretations have been proposed for the name. Whatever else it means, it undoubtedly suggests the self-existence and all-sufficiency of God. Moses then argued that the people would not believe him when he told them that God had sent him to deliver them from Egypt. In response God gave him three signs: When he cast his shepherd’s rod to the ground, it became a serpent. When he put his hand to his bosom, it became leprous. He was also told that when he would pour water from the Nile on the ground, it would become blood (Ex 4:1-9). Even armed with these powerful evidences of the presence of God with him, Moses raised still another objection, “O Lord, I’m just not a good speaker. I never have been, and I’m not now, even after you have spoken to me. I’m clumsy with words” (v 10, NLT). God told him that he would teach him what to say, but despite such assurance, Moses asked God to send someone else. In anger mingled with compassion, God made Moses’ brother, Aaron, the spokesman, but said his instructions would still be given directly to Moses.

Return to Egypt

Moses took his wife and sons and set out for Egypt, telling his father-in-law only that he wanted to go back to Egypt to visit his kinsmen there (Ex 4:18). The biblical account says he put his wife and sons on the same donkey to journey back to Egypt (v 20). The fact that all three rode the same animal indicates that both children were quite young and had not been born in the early years of Moses’ marriage. At a lodging place along the way a strange thing happened. The Lord met him and sought to kill him (v 24), apparently because Moses had failed to circumcise the baby before leaving Midian. When Zipporah realized that Moses’ life was in danger, she performed the rite herself and said to her husband, “What a blood-smeared bridegroom you are to me!” (v 25, NLT). Whatever else may have been involved in this unusual encounter with God, it was a solemn reminder that the one who was to be the leader of the covenant people must not himself neglect any part of the covenant (Gn 17:10-14).

God told Aaron (who was still in Egypt) to go to the mountain where Moses had encountered God at the burning bush and meet his brother there. Moses told Aaron everything that had happened, and together they went to Egypt, gathered the elders together, and informed them of these matters. When Moses and Aaron performed the signs in the presence of the people, they believed these leaders had been sent by God to deliver them from their affliction (Ex 4:30-31).

The Third 40 Years—From Egypt to Canaan

The Encounter with Pharaoh

Soon after his return to Egypt, Moses, accompanied by Aaron, went to Pharaoh and repeated the demands of the Lord, “Let my people go, for they must go out into the wilderness to hold a religious festival in my honor” (Ex 5:1, NLT). Pharaoh rejected the demand with the observation that he had never heard of this God of Moses. When one realizes that Egyptian kings considered themselves to be gods, the affront to Pharaoh becomes even more acute. Not only did he reject Moses’ demands, but he intensified the burdens of the Hebrews. Their work had up until then required them to make brick using straw provided for them, but now Pharaoh said they would have to gather their own straw and still produce the same number of bricks. The Hebrews turned in anguish and anger to Moses and blamed him for making them offensive in the sight of Pharaoh. Even Moses could not understand the turn of events and complained bitterly to God. God reassured Moses that he would deliver the Hebrews from their bondage, and moreover, he would bring them into the land he had promised Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob. He then instructed Moses to return to Pharaoh and repeat the demand to release the Hebrews upon threat of severe reprisal if the demand were ignored.

Ushered again into Pharaoh’s presence, Moses repeated his request for release of the Israelites. He attempted to impress Pharaoh by turning his rod into a serpent, but the Egyptian wise men, through their secret arts, were able to duplicate the miracle, so Pharaoh’s heart remained hardened and he would not listen to Moses. In rapid succession Moses brought nine plagues upon the land of Egypt to show the omnipotence of God to force the compliance of Pharaoh. These included a plague in which the water of the Nile turned to blood, a plague of frogs, one of gnats, then of flies, a plague on the livestock, boils on the people, plagues of hail, locusts, and complete darkness. During the plagues of the frogs, flies, hail, locusts, and darkness, Pharaoh was distraught and would temporarily relent and agree to Moses’ demands, but as soon as the plague was lifted, his heart hardened and he would retract his promise. The outcome of the first nine plagues was terrible devastation of the land of Egypt, but the Israelites were not released. There was yet one more plague in store, the most terrible of all.

The First Passover

God told Moses that there remained one more plague in store for the Egyptians: “All the firstborn sons will die in every family in Egypt, from the oldest son of Pharaoh, who sits on the throne, to the oldest son of his lowliest slave. Even the firstborn of the animals will die” (Ex 11:5, NLT). Furthermore, he assured Moses that the plague would not touch a single household of the Hebrews, “Then you will know that the Lord makes a distinction between the Egyptians and the Israelites” (v 7, NLT).

God instructed the people through Moses and Aaron to make their preparations for leaving the land in haste. They were to go to the Egyptians and ask them for their jewels of silver and gold (Ex 11:2-3), a request to which the Egyptians agreed, perhaps out of fear of the Hebrews and in the belief that the gifts would bring about an end of the terrors that had struck the land. The Hebrews were also instructed to prepare a lamb for each family—small families could share—for the last meal to be eaten in the land of Egypt (a rite that became the pattern for the Jewish observance of the Passover for many centuries). Blood of the lamb was to be put on the doorposts and lintels of the houses in which the Passover meal was being eaten that night. The Hebrews were promised that wherever the blood was on the door, no harm would come to that household. They were also instructed to prepare unleavened bread. At midnight the death angel of the Lord killed all the firstborn in the land of Egypt, from the firstborn of Pharaoh himself to the lowest captive in a dungeon; not a single house of the Egyptians escaped tragedy. When Pharaoh saw what had happened, he ordered Moses and the people to leave the land at once (12:31-32). The biblical record says that about 600,000 Hebrew men left Egypt. Together with women and children, the total would have been in excess of 2 million people.

The Exodus from Egypt

The exodus is the central event of the OT and marks the birth of Israel as a nation. The Jewish people still look back to that event as the great redemptive act of God in history on behalf of his people, much as Christians look upon the cross as the great redemptive act of their faith.

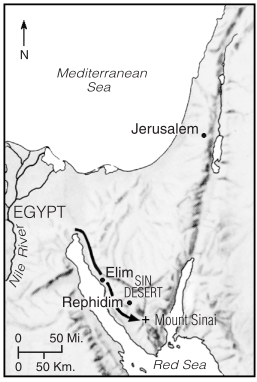

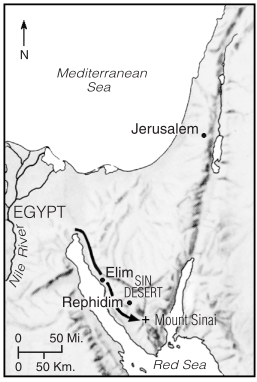

Moses Leads the Israelites to Mount Sinai

The exact route taken by the Hebrews out of Egypt cannot be determined today, though many possibilities have been proposed. They did not take the shortest, most direct route to Canaan (which would have been about a 10 days’ journey along the Mediterranean coastline), but set out in the direction of Mt Sinai, where Moses had earlier met God at the burning bush. As a sign that Moses had been sent to deliver the people, God told Moses he would bring them to that same spot, where they would worship God (Ex 3:12). The Hebrews did not forget the request of Joseph to carry his bones with them when they returned to their own land (Gn 50:25; Ex 13:19).

As the people journeyed, they were preceded by a pillar of cloud during the day and a pillar of fire at night. The cloud represented the presence of God with his people and guided them along the route they should travel.

Back in Egypt, Pharaoh was having second thoughts about letting the Hebrews leave the land and decided to pursue them with his army and bring them back. When the Hebrews saw the approaching cloud of dust and realized that the Egyptian army was pursuing them, they were terrified. The sea lay ahead of them and the Egyptians were behind; there seemed to be no way of escape. The people turned on Moses, blaming him for bringing them out of Egypt. God again assured them that they did not need to be afraid or do anything to defend themselves. He promised to fight the battle for them and give them victory (Ex 14:14).

The Lord parted the water of the Sea of Reeds (traditionally but erroneously referred to as the Red Sea) by a strong east wind and allowed the Israelites to pass through the sea on dry ground to the other side. The Egyptians rushed after the Israelites, following them into the dry bed of the sea. But before they reached the other side, the waters rushed back together, destroying the Egyptian army in the midst of the sea and leaving the Israelites safe on the other side. The people celebrated their great deliverance in song (Ex 15) and then continued their journey. The narrative that follows describes the struggle of the Israelites to survive in the desert—problems of food and water, internal dissension, murmurings against Moses, and battles with enemies. Through all their experiences, Moses towers as the unifying force and great spiritual leader.

In spite of having seen God’s great act of deliverance so recently, the faith of the Israelites was not strong. Three days later they came to a place where the water was not fit to drink, and they began complaining against Moses. The Lord showed Moses how to purify the water, and the people’s needs were satisfied (Ex 15:22-25). When they reached the wilderness of Sin, they complained again, this time because of lack of food. God met their need by supplying manna, a breadlike substance that would serve as their food until they came to Canaan (16:1-21). Later, camped at Rephidim, the people complained again, this time for lack of water. Once again God met their needs by supplying water from the rock at Horeb (17:1-7). The Amalekites attacked them while they were still camped at Rephidim, but God gave a great victory to the Israelites (vv 8-13).

Moses and the people reached Sinai and camped there. Jethro came to visit, bringing Moses’ wife and sons. Zipporah had apparently decided to return with her children to stay with her father rather than to go on to Egypt with Moses. It was a joyful reunion, and Jethro made a burnt offering and sacrifices to God (an act that has evoked the suggestion that Jethro was a true worshiper of God, though nothing is known of his links to the Hebrew faith). When Jethro observed Moses trying to settle all the disputes and problems of the Hebrews unaided, he proposed that Moses delegate responsibility for some of the lesser matters to able men chosen from among the people. Moses accepted the suggestion, and shortly afterward Jethro returned to his own land. He did not remain at Sinai to participate in the ratification of the covenant (Ex 18:13-27).

Giving of the Law at Sinai

God had kept his promises to Moses. He had delivered the Hebrews from their Egyptian bondage and brought them to the very place where he had commissioned Moses to be their leader. He was now ready to enter into a covenant relationship with Israel. Amid a spectacular and terrifying scene of lightning, thunder, thick clouds, fire, smoke, and earthquake, God descended to the top of Sinai and called Moses to come up the mountain, where he remained 40 days to receive the law that would become the basis of the covenant.

At Sinai, God was revealed as the God who demands exclusive allegiance in all areas of life and, at the same time, as the God who desires personal fellowship with his people.

Apostasy of the People

While Moses tarried on Mt Sinai, the people below became impatient and skeptical about his return, so they went to Aaron and asked him to make idols for them to worship. They contributed the gold earrings they were wearing. “Then Aaron took the gold, melted it down, and molded and tooled it into the shape of a calf. The people exclaimed, ‘O Israel, these are the gods who brought you out of Egypt!’ ” (Ex 32:4, NLT). The next day they joined in the worship of the idol with sacrifices and revelry. God told Moses what was taking place below and angrily declared that he was going to destroy the people but would make a great nation of Moses and his descendants. Moses immediately interceded on behalf of the people, and God’s wrath abated. Moses descended the mountain, carrying the two tablets of stone on which the law had been written, but when he entered the camp and saw what was taking place, he could not restrain his anger. He threw the stone tablets to the ground, ground the golden calf to powder, mixed it with water, and forced the people to drink it. He turned angrily to Aaron and demanded an explanation for the great sin that had been committed. Aaron lamely tried to shift the blame by minimizing his own role: “I threw them [the gold] into the fire—and out came this calf!” (v 24, NLT). Moses called for volunteers to carry out God’s judgment on the people for the great sin they had committed. Men of the tribe of Levi responded and executed about 3,000 men. Later they were commended and rewarded (Dt 33:9-10). Moses again interceded for the people, requesting that he be destroyed with the rest if God could not forgive them. God relented and promised Moses that the angel of the Lord would go with them still (Ex 32:34).

Then Moses made a special request that he might be allowed to see the glory of the Lord. God instructed Moses to hew out two more tablets of stone like the ones he had destroyed and to return to the top of the mountain the next day. There the Lord passed before him and proclaimed his name: “I am the Lord, I am the Lord, the merciful and gracious God. I am slow to anger and rich in unfailing love and faithfulness” (Ex 34:6, NLT). Moses remained on the mountain another 40 days, where he received renewed warnings against idolatry and further instructions from the Lord, together with another copy of the Ten Commandments on tablets of stone. When Moses came down from the mountain, he was not aware that the skin of his face shone as a result of talking with God. At first the people were afraid to come near him, but he called them together and repeated all the Lord had said to him on the mountain. Afterward, he covered his face with a veil, which he removed only when he went into the presence of the Lord. Paul said the purpose of the veil was to prevent the people from seeing the heavenly light gradually fade from Moses’ face (2 Cor 3:13).

The Tabernacle and Establishment of the Priesthood

When Moses went up to the mountain the first time to receive the law from God, he was instructed to collect materials to be used in the construction of the tabernacle or tent. Gold, silver, bronze, blue and purple and scarlet yarn, fine twined linen, goats’ hair, tanned rams’ skins, goatskins, and acacia wood would be needed, along with oil for the lamps, spices for the anointing oil and for the fragrant incense, onyx stones, and stones for setting (Ex 25:3-7). The pattern for construction was also given to him, together with the ritual to be used for the consecration of the priests. A man named Bezalel was put in charge of the construction of the tabernacle, assisted by Oholiab (31:1-6). The tabernacle was portable like a tent so that it could be taken down and moved from place to place as the Hebrews continued their journey toward Canaan.

In addition to giving Moses directions for the tabernacle, God also instructed him concerning the sacrifices that were to be brought: the burnt offering, grain offering, peace offering, sin offering, and guilt offering (Lv 1–7). The solemn ceremony for ordaining Aaron and his sons as priests and for inaugurating the worship practices were to be performed by Moses (chs 8–9).

Sometime after this solemn inauguration of the religious ritual actually took place, Nadab and Abihu, two of Aaron’s four sons, offered unauthorized fire before the Lord. A fire came out from the Lord and destroyed them. Moses forbade Aaron and his sons Eleazar and Ithamar to express grief because of the sinfulness of the act (Lv 10:1-7). The nature of their sin is difficult to determine, but it surely involved a violation of God’s holiness. Therefore, it is appropriate that a large part of the remainder of the book of Leviticus gives regulations that stress the holy living that God expected from his people.

From Sinai to Kadesh

A year had elapsed from the time the Israelites left Egypt until the census was taken (Nm 9:1). God reminded the people that it was time to observe the Passover, which they did, and a month later they set out from Sinai and came to the wilderness of Paran. Along the way they complained about the unvarying diet of manna and they longed for the fish, cucumbers, melons, leeks, onions, and garlic they had eaten in Egypt (11:4-6). In anger God sent quail in abundance, but even while the people were devouring the meat, God sent a great plague that killed many Israelites. The complaining attitude of the people was shared even by Miriam and Aaron. They began to speak against the Cushite woman Moses had married (12:1-2). It is not certain whether the Cushite was an Ethiopian or whether this was another way of referring to Zipporah. If Moses did marry a second time, no mention is made of it elsewhere in the OT. Moses made no reply to the accusations of his brother and sister. It was not necessary, for God intervened in defense of his servant. He smote Miriam with leprosy for her part in speaking against Moses, and when Aaron saw what had happened to Miriam, he acknowledged that they both had sinned. Miriam’s leprosy was removed in response to Moses’ fervent intercession.

Moses Leads the Israelites toward the Promised Land

While the people were encamped at Kadesh (also called Kadesh-barnea—Nm 32:8) in the wilderness of Paran, Moses sent 12 men into Canaan, one from each tribe, to spy out the land in preparation for the Israelite entry. After 40 days the spies returned and, though they acknowledged that the land was fertile and inviting, 10 of them were afraid of the Canaanite inhabitants and advised against going into the land. Only Joshua and Caleb were willing to go ahead and occupy the territory. The entire congregation joined the protest against going in and determined to choose a new leader and return to Egypt rather than risk death by the sword in Canaan. They threatened to stone Moses and Aaron. At that moment God intervened and would have destroyed all the people on the spot except for the intervention of Moses (13:1–14:19). He declared that, if God did not bring the people into Canaan, the nations round about would conclude that the God of the Israelites was unable to bring them into the land. Once again God acquiesced to Moses’ request to pardon the people but said that none of them 20 years and older who had complained against him would be allowed to enter the land. All the people would wander in the wilderness for 40 years until that generation died, and then their children would be allowed to enter Canaan (14:29-33). When they heard the Lord’s sentence upon them, the people quickly decided to lift the sentence of judgment by entering the land at once, but God was not with them, and they suffered a disastrous defeat at the hands of the Amalekites and Canaanites.

Forty Years in the Wilderness

Very little is known about events during the 40 years of wilderness wanderings. In spite of the judgment that had already come upon them, the people did not seem to change their ways. A man named Korah led another rebellion against the authority of Moses and Aaron. God would not listen to the pleas of Moses and Aaron on behalf of these dissidents (Nm 16:22-24), but told the congregation to separate itself from the tents of Korah and his conspirators. While the people watched, the ground split open and swallowed up the rebellious factions together with their households and all their possessions. Though the rest of the Israelites witnessed the fate of the rebels, it did not deter them from again turning on Moses and Aaron. At this, God told Moses to remove himself from the murmuring congregation in order that he could take vengeance. Though Moses offered atonement for the people’s sins, 14,700 died by plague before the punishment was ended. To demonstrate further to the people that Moses was his chosen leader, the Lord instructed Moses to take rods, one for each tribe, and to deposit them in the tent of meeting. God would cause the rod of the man chosen by him to sprout, and so silence the murmurings of the people. The rod belonging to Aaron sprouted and budded and bloomed, but the people only complained more.

As the people neared the end of their years of wilderness wanderings, Miriam died in Kadesh and was buried there (Nm 20:1). Soon after, the people began to complain once more for lack of water. God instructed Moses to speak to a rock that would bring forth water to satisfy the needs of the people. Instead of speaking to the rock, Moses struck it twice with his rod. The water came forth, but God rebuked Moses and Aaron: “Because you did not trust me enough to demonstrate my holiness to the people of Israel, you will not lead them into the land I am giving them!” (v 12, NLT). The nature of the sin is not clear, but Moses and Aaron were apparently taking to themselves honor that belonged to God alone. Because of the sin, they were denied the privilege of leading the Israelites into the Promised Land. The punishment may seem too severe for the sin, but it shows that the privileged role of leadership given to Moses and Aaron carried with it an unusual measure of responsibility.

The people then journeyed from Kadesh to Mt Hor on the border of the land of Edom, where Aaron died. Moses took his priestly garments from him and gave them to Eleazar, his son, thereby transferring the priestly office (Nm 20:28).

As the people came closer to their destination, resistance on the part of the native population increased. There was a skirmish with the king of Arad and his forces at Hormah, resulting in a victory for Israel (Nm 21:1-3). As they journeyed around Edom, some of the Israelites began speaking against God and Moses because there was no food or water and they were tired of eating manna. This time the Lord sent poisonous snakes among the people, and many of them died of the venomous bites. Those who had not yet been bitten came to Moses, acknowledged their sin, and asked that the serpents be removed from their midst. God instructed Moses to make a serpent of bronze and set it on a pole. If a person bitten by a serpent looked up at the bronze serpent, he or she would live.

As the Israelites approached the territory of Sihon, king of the Amorites, they sent messengers asking permission to pass peaceably through his land. Instead of granting the request, Sihon gathered his army together and fought against Israel. He was killed in the battle, and his land and cities were taken and occupied by the Hebrews (Nm 21:21-25).

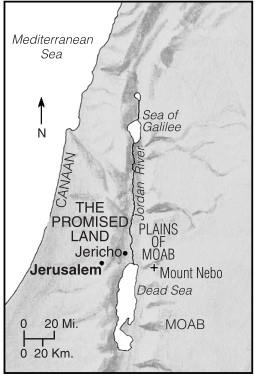

Arrival at the Jordan River

After their victory over Sihon, the Israelites set out again and encamped in the plains of Moab on the east side of the Jordan River facing Jericho, in full view of the Promised Land. The Moabites were terrified by the presence of these people because they had heard what happened to the Amorites. Their king, Balak, hired a magician named Balaam to curse the Israelites. Three times Balaam attempted to curse them, but each time God turned his words into a blessing (Nm 22–24). Though unable to curse the Israelites, Balaam was responsible for an even greater calamity. He advised the Moabites to entice the Israelites to sacrifice to their gods and bow down to them (Nm 25:1-3; 31:16; 2 Pt 2:15; Rv 2:14). While the people were worshiping the Moabite deity, Baal of Peor, God’s anger was kindled against them, and he sent a plague that killed 24,000 of them (Nm 25:9). It was Israel’s first encounter with the seductive allurement of licentious idolatry and an ominous foreview of what would happen after they settled down in Canaan. Their continued attraction to idolatry would be their final undoing.

After the plague, God instructed Moses and Eleazar to take another census of the people like the one almost 40 years earlier. A whole generation of Israelites had died in the wilderness, but they had been replaced by an almost equal number, so that now there were 601,730 men 20 years and older who were able to go to war (Nm 26:51). Not a man remained of those who had been counted in the first census, except Caleb and Joshua.

The Lord instructed Moses to lay hands on Joshua and commission him as the new leader in the sight of Eleazar the priest and all the congregation (Nm 27:12-23). In addition, the Lord gave Moses instructions concerning feasts and offerings and vows (chs 28–30). God ordered Moses, as his last act as leader, to avenge the Israelites on the Midianites. In that battle the armies of Israel gained a great victory over the Midianites, killing their kings, their men, and also Balaam.

The Lord gave instructions to Moses concerning the boundaries that would mark the Promised Land and named the men who would divide the land among the tribes (Nm 34). He also ordered that 48 cities be given to the Levites, the priestly tribe, as their portion. Six of these were designated as cities of refuge where murderers could flee so that they would not be killed by those seeking vengeance without having an opportunity to stand before the congregation for judgment (ch 35).

Moses’ Death

The book of Deuteronomy has often been called Moses’ valedictory speech to the people, for in it Moses is not merely the chief speaker but the only speaker. With the congregation of his people gathered before him, he rehearsed all that God had done for them since leaving Sinai, and he reminded them of their failure to enter the Promised Land 38 years earlier (Dt 2:14). He recalled his plea that God would let him cross the Jordan and see the land that was to be the home of the people, but God responded that Moses would only be allowed to view the land from the top of Pisgah. Moses then exhorted the people to obey the statutes and ordinances that had been given to them in order to experience God’s blessings in the land.

The Death of Moses

Not allowed to enter the Promised Land, Moses climbed Mt Nebo to look at it just before his death.

As the day of Moses’ death approached, the Lord ordered Moses and Joshua to present themselves at the tent of meeting in order for Joshua to be commissioned as the new leader (Dt 31:14-23). Before his death, Moses pronounced a blessing upon all the Israelites (ch 33). Having completed these tasks, Moses went up from the plains of Moab to Mt Nebo, and to the top of Pisgah. From there God showed him the land promised long ago to Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob—the land that was soon to be the home of the wandering Israelite tribes. Again God told him that he would not be allowed to cross over the Jordan. Moses died there and God buried him somewhere in the valley in the land of Moab opposite Beth-peor (34:6). Moses was 120 years old when he died, and the Israelites mourned his death for 30 days. The finest tribute to Moses is found in the closing words of the book of Deuteronomy, “There has never been another prophet like Moses, whom the Lord knew face to face” (v 10).

Moses in the New Testament

All Jews and Christians in apostolic times considered Moses the author of the Pentateuch. Such expressions as “the law of Moses” (Lk 2:22), “Moses commanded” (Mt 19:7), “Moses said” (Mk 7:10) “and Moses wrote” (12:19) shows that his name was synonymous with the OT books attributed to him. He is mentioned in the NT more than any other OT figure, a total of 79 times. His role as lawgiver is emphasized more than any other aspect of his life (Mt 8:4; Mk 7:10; Jn 1:17; Acts 15:1). He appears at the transfiguration of Jesus as the representative of OT law, along with Elijah as the representative of OT prophets (Mt 17:1-3).

Moses’ role as prophet is also mentioned in the NT. As a prophet, he spoke of the coming Messiah and his sufferings (Lk 24:25-27; Acts 3:22). The NT also draws from the life and experiences of Moses to show patterns of life under the new covenant. The nativity story of Jesus parallels the Mosaic story of the infant deliverer being rescued from the evil designs of an earthly despot (Mt 2:13-18). Jesus’ proclamation of a new law in his Sermon on the Mount parallels the giving of the law at Sinai (Mt 5–7) and presents Jesus as the authoritative interpreter of the will of God. Contrast between the old law and the new relationship with God is especially marked in the book of Galatians. The comparison of Moses with Christ is an important emphasis of the book of Hebrews (Heb 3:5-6; 9:11-22). John contrasted the law that was given through Moses with the grace and truth that came through Jesus Christ (Jn 1:17). He also contrasted the manna in the wilderness to Jesus as “the bread of life” (6:30-35).

Other references to Moses or to events associated with him include his birth (Acts 7:20; Heb 11:23), the burning bush (Lk 20:37), the magicians of Egypt (2 Tm 3:8), the Passover (Heb 11:28), the exodus (3:16), crossing of the sea (1 Cor 10:2), the covenant sacrifice at Sinai (Mt 26:28), the manna (1 Cor 10:3), the glory on Moses’ face (2 Cor 3:7-18), water from the rock (1 Cor 10:4), the bronze serpent (Jn 3:14), and the song of Moses (Rv 15:3).

See also Egypt, Egyptian; Exodus, The; Israel, History of; Plagues upon Egypt; Priests and Levites; Tabernacle; Temple; Commandments, The Ten; Wilderness Wanderings.