Open Bible Data Home About News OET Key

A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W XY Z

Tyndale Open Bible Dictionary

Intro ← Index → ©

JESUS CHRIST

Messiah, Savior, and founder of the Christian church.

In providing a biography of Jesus Christ it must be borne in mind that each of the Gospels has its own distinctive purpose. Matthew, for instance, presents Jesus as the messianic King, whereas the emphasis in Mark is more on Jesus as the servant of all. Luke tends to present Jesus in a softer light, showing particularly his amazing compassion to the less fortunate, whereas John plunges the reader into a deeper and more spiritual understanding of Jesus. These different aims caused the four Evangelists to select and arrange the events of Jesus’ life differently, resulting in a fourfold portrait of the same man. It was undoubtedly for this reason that the Christian church preserved four Gospels instead of only one.

The following sections present the main events in what may be regarded as the chief stages of the life of Jesus. These stages show a definite progression from Christ’s incarnation to his cross. The amount of space devoted to each stage in each of the Gospels is dictated by theological rather than biographical interest. The whole presentation of Christ’s life centers on the cross and the subsequent triumphant resurrection and is more an account of God’s message to humanity than a plain historic account of the life of Jesus.

Preview

• The Incarnation

• The Birth of Jesus

• Life in Nazareth

• Preparatory Events

• The Early Ministry of Jesus in Judea and Samaria

• The Period of the Galilean Ministry

• On the Way to Jerusalem

• The Final Days in Jerusalem

• The Betrayal and Arrest

• The Trial

• The Crucifixion

• The Burial, Resurrection, and Ascension

The Incarnation

The major event of this initial stage was the Incarnation. Only Matthew and Luke give accounts of Jesus’ birth. John goes back and reflects on what preceded the birth.

It may seem strange that John began his Gospel with a reference to the Word (Jn 1:1), but it is in this way that he delivers to the reader an exalted view of Jesus. John saw Jesus as existing even before the creation of the world (v 2). In fact, he saw him as having a part in the act of creation (v 3). Therefore, when Jesus was born, it was both an act of humiliation and an act of illumination. The light shone, but the world preferred to remain in darkness (vv 4-5, 10). Therefore, anyone coming to John’s records of the life of Jesus would know at once, before even being introduced to the man named Jesus, that here was the record of no ordinary man. The account of his life and teachings that followed could not be properly understood except against this background of his preexistence.

The Birth of Jesus

John simply wrote that the Word became flesh and dwelt among us. Matthew and Luke fill in some of the details of how this happened. There is little in common between the two accounts. Each approaches the subject from a different point of view, but the supernatural is evident in both. The coming of Jesus is announced beforehand, through dreams to Joseph in Matthew’s account (Mt 1:20-21) and through an angel to Mary in Luke’s account (Lk 1:26-33). Matthew leaves his readers in no doubt that the one to be born had a mission to accomplish—to save people from their sins (Mt 1:21). Luke sets his story of Jesus’ coming in an atmosphere of great rejoicing. This is seen in the inclusion of some exquisite songs, which have formed part of the church’s worship ever since (Lk 1:46-55, 68-79). The homage of the wise men in Matthew 2:1-12 is significant because it sets the scene for a universalistic emphasis that links the beginning of the Gospel to its ending (cf. Mt 28:19-20). A similar emphasis is introduced in the angel’s announcement to the shepherds in Luke 2:14 and in Simeon’s song (Lk 2:32), where he predicts that Jesus would be a light for Gentiles as well as a glory for Israel. The flight into Egypt for safety (Mt 2:13-15) shows the contribution of a gentile nation in providing protection for a Jewish child.

One feature of the birth stories in Matthew and Luke is that they are both linked to genealogies. It is difficult to harmonize these genealogies since they appear to be drawn from different sources, but the purpose in both cases is to show that Jesus was descended from Abraham and David. The latter fact gave rise to Jesus’ title Son of David.

Luke was the only Gospel writer who attempted to link the coming of Jesus with events in secular history. Although problems arise over the dating of the census of Quirinius (Lk 2:1-2), the firm setting of the contemporary scene is highly significant because the Christian faith is a historic faith centered on a historic person.

Life in Nazareth

The years of Jesus Christ’s human development are given only a few lines in the Gospels. Details are given of only one incident belonging to the period of childhood, the discussion of the 12-year-old Jesus with the Jewish teachers in the temple (Lk 2:41-50). This event is a pointer to one of the most characteristic features of Jesus’ later ministry: his display of irrefutable wisdom in dialogue with his Jewish contemporaries. It also reveals that at an early age Jesus was acutely aware of a divine mission. Nevertheless, Luke notes that in Jesus’ formative years he was obedient to his parents (v 51). It is assumed that during 30 years at Nazareth Jesus learned the carpenter’s trade from Joseph and became the village carpenter after Joseph’s death. However, there is no account of this period in the Gospels. This has led to many fantastic imaginings about Jesus’ childhood. Many of these fables are recorded in apocryphal gospels, but Luke’s account is unembellished. Its remarkable reserve is a strong indication of its historical reliability.

Preparatory Events

All four Gospels refer to a brief preparatory period that immediately preceded the commencement of Christ’s public ministry. This period focused on three important events.

The Preaching of John the Baptist

John the Baptist appeared in the wilderness and caused an immediate stir in Judea, particularly as a result of his call to repentance and to baptism (Mt 3:1-6). John was like one of the OT prophets, but he disclaimed any importance in his own office except as the herald of a greater person to come. His stern appearance and uncompromising moral challenge effectively prepared the way for the public appearance of Jesus (Lk 3:4-6). It is important to note that John the Baptist’s announcement of the imminent coming of the kingdom (Mt 3:2) was the same theme with which Jesus began his own ministry (4:17). This shows that John the Baptist’s work was an integral part of the preparation for the public ministry of Jesus. The same may be said of the rite of baptism, although John recognized that Jesus would add a new dimension in that he would baptize with the Holy Spirit and with fire (3:11). As the forerunner of Jesus Christ, John proclaimed that the one to follow would not only be greater than he but would also come with high standards of judgment (v 12). The stage was therefore set in stern terms for the initial public act of Jesus—his willingness to be baptized (Mt 3:13-15; Lk 3:21).

The Baptism of Jesus

John’s baptism was a baptism of repentance. Since Jesus submitted to this, are we to suppose that Jesus himself needed to repent? If this were the case, it would involve the assumption that Jesus had sinned. This is contrary to other evidence in the NT. But if Jesus did not need to repent, what was the point of his requesting baptism at the hands of John? Jesus had come on a mission to others, and it is possible that he deliberately submitted to John’s baptism in order to show that he was prepared to take the place of others. This explanation is in line with Paul’s later understanding of the work of Jesus Christ (2 Cor 5:21). Matthew is the one Evangelist who records John’s hesitation to baptize Jesus (Mt 3:14-15).

The most important part of the baptism of Jesus was the heavenly voice, which declared pleasure in the beloved Son (Mt 3:17). This announcement by God was the real starting point of the public ministry of Jesus. It revealed that the ministry was no accident or sudden inspiration on the part of Jesus. He went into his work with the full approval of the Father. A further important feature is the part played by the Holy Spirit in this scene. The dovelike description is full of symbolic meaning (v 16). It was not just an inner experience that Jesus had. The activity of the Spirit in the ministry of Jesus, although not much emphasized in the Gospels, is nevertheless sufficiently evident to be indispensable to a true understanding of Jesus Christ.

The Temptation of Jesus

Jesus’ baptism showed the nature of his mission. The temptation showed the nature of the environment in which he was to minister (Mt 4:1; Lk 4:1-2). Confrontation with adverse spiritual forces characterized Jesus’ whole ministry. Only Matthew and Luke record details of the temptations to which Jesus was subjected by the devil. All these temptations present shortcuts that, if pursued, would have deflected Jesus from his vocation. The record leaves us in no doubt that Jesus gained the victory. Both Gospels show that he accomplished this by appealing to Scripture. Jesus is also seen in this event as a genuine human who, like all other humans, was subject to temptation. The writer of the Letter to the Hebrews notes that this fact qualified Jesus to act as High Priest and to intercede on behalf of his people (Heb 2:18; 4:15).

The Early Ministry of Jesus in Judea and Samaria

Only John’s Gospel tells of the work of Jesus in Judea following his baptism. It first describes his calling of two disciples, John and Andrew (Jn 1:35-39). This event is set against the background of John the Baptist’s announcement of Jesus as the Lamb of God who was to take away the sin of the world (v 29). These first two disciples were soon joined by three others: Peter, Philip, and Nathanael (vv 41-51). These five formed part of the nucleus of Jesus’ followers who came to be known as the Twelve. One feature of John’s account is the early recognition by the disciples of Jesus as Messiah (Jn 1:41) and Son of God (v 49).

Soon after Jesus began his ministry in Jerusalem, John relates an incident at Cana in Galilee in which water was turned into wine (Jn 2:1-10). This event is important in John’s account because it is the first of the signs that he records (v 11). He saw Jesus’ miracles as “signs” of the truth of the gospel rather than as mere wonders.

John sets two incidents at Jerusalem in this initial period. The first is the cleansing of the temple (Jn 2:13-16). Matthew, Mark, and Luke all place this event just before Jesus’ trial, but John places it at this early stage. The moral intention of Jesus’ work is seen in his driving out the money changers who were profiting from worshipers more than was appropriate. This was apparently acceptable to Judaism but was unacceptable to Jesus. The other Evangelists imply that this authoritative act was the event that sparked the final hostility of his opponents. John tells the story for a theological reason; to him, the cleansing of the temple was a parable telling of what Jesus had come to do.

The other incident in Jerusalem is the meeting between Jesus and Nicodemus (Jn 3). Nicodemus was closely associated with Judaism, yet he was also searching for truth. He was unable to understand, however, the spiritual truth about being born again through the Spirit.

John’s story then moves from Judea to Samaria and the story of the Samaritan woman at the well (Jn 4:1-42). Jesus used her physical thirst to point to her deeper spiritual thirst. She realized that Jesus had something to offer her that she had not previously known. As a result of this woman’s experience and testimony, many of the Samaritan people came to believe in Jesus as the Savior of the world (v 42). In this case John intends that his readers would appreciate the fuller significance of the words of Jesus by viewing them in the light of the resurrection.

The Period of the Galilean Ministry

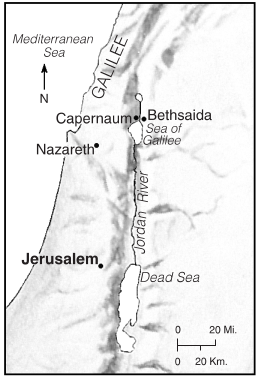

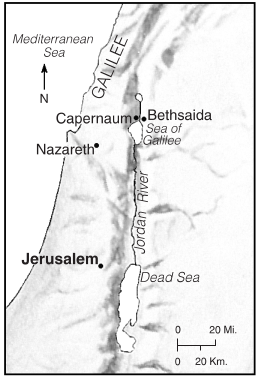

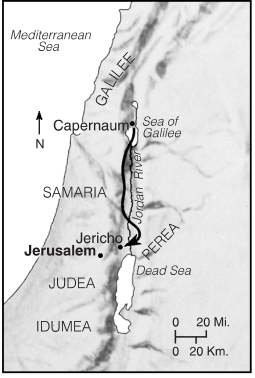

Important Places in Jesus’ Ministry in Galilee

After returning to his hometown, Nazareth, from Capernaum, Jesus preached in the villages of Galilee and sent his disciples out to preach as well. After meeting back in Capernaum, they left by boat to rest, only to be met by the crowds who followed the boat along the shore.

Almost all the information on this period is found in the synoptic Gospels (Matthew, Mark, and Luke.) It may be conveniently divided into three sections. The first briefly outlines the events leading up to the choosing of the Twelve; the second deals with Jesus’ withdrawal from northern Galilee; and the third deals with his departure for Jerusalem. While the synoptic Gospels concentrate exclusively on the events in Galilee, John’s account indicates that there were some visits by Jesus to Jerusalem during this period. Also, John records another incident at Cana, where the son of a Capernaum official was healed. This is noted as the second of Jesus’ signs (Jn 4:54). It is chiefly important because of the extraordinary faith of the father, who was prepared to take Jesus at his word.

The Calling of the Disciples

In the synoptic Gospels there is an account of the initial call to four of the disciples to leave their fishing boats and to become fishers of men (Mt 4:18-22; Mk 1:16-20; Lk 5:1-11). They had already met Jesus and must have had some idea what was involved in following him. Jesus did not at this time appoint them to be apostles, but this call was an indispensable step toward the establishment of the Twelve as a group. Setting apart a particular number of disciples formed an important part of the ministry of Jesus. The miraculous catch of fish, which preceded the call of the disciples in Luke’s account, served to highlight the superiority of the spiritual task of catching people rather than fish.

Another significant call came to Levi, otherwise known as Matthew (Mt 9:9; Mk 2:13-14; Lk 5:27-28). As a tax collector, he was of a different type from most of the other disciples. He would certainly have been despised by his Jewish contemporaries because of his profession. But his inclusion in the special circle of Jesus’ disciples shows the broad basis on which these men were chosen. One of the others, Simon the Zealot, may have belonged to a group of revolutionaries who were religious as well as political. Even a man like Judas Iscariot was numbered among the Twelve, and he would later betray Jesus to his enemies for a small sum of money. Jesus accepted them as they were and molded them into men who later came to learn how to be totally dependent on God and the power of his Spirit.

Sermon on the Mount

The Gospel of Matthew presents a substantial sample of Jesus’ teachings commonly called the Sermon on the Mount (Mt 5:1–7:29). Some of the same material occurs in Luke in a different context and different arrangement. It is possible that Jesus often repeated his teachings on different occasions and with different combinations. Matthew’s record of the Sermon on the Mount presents an impressive body of teaching, mainly of an ethical character. In it Jesus upholds the Mosaic law and at the same time goes beyond it. The beginning of this sermon has been called the Beatitudes (5:3-12). It commends moral and spiritual values. The teachings recorded in this section were radical, but not in a political sense. The Sermon on the Mount may be taken as a fair sample of the kind of discourses that must have abounded in the ministry of Jesus.

Jesus as Healer

Throughout the Gospels there are records of miracles involving Jesus healing people. There are more of these miracles than any other type. In a section in Matthew devoted to a sequence of healings (Mt 8:1–9:34), a leper, a centurion’s servant, Peter’s mother-in-law, a demoniac, a paralytic, a woman with a hemorrhage, blind men, and a man who was mute—all were healed. In addition, Jairus’s daughter was raised from the dead. This concentration of healings focuses on Jesus as a miracle worker, but throughout the Gospels there is no suggestion that Jesus healed by magical means. In some cases an individual’s faith was acknowledged (8:10; 9:22). In at least one incident, the healing was accompanied by an announcement of the forgiveness of the sins of the one healed (Mt 9:2; Mk 2:5). This shows that Jesus considered spiritual needs to be of greater consequence than the physical problems.

In view of the widespread belief in the powerful influence of evil spirits over human lives, it is of great significance that Jesus is seen exercising his power of exorcism over demons. Jesus’ ministry was set in an atmosphere of spiritual conflict, so the confrontations between the forces of darkness and the Light of the World were to be expected. Those who explain away these cases of demon-possession in psychiatric terms miss this key feature of Jesus’ ministry. Each time he exorcised a demon, he was demonstrating victory, which reached its most dramatic expression in his victory over death at his resurrection.

In addition to the healing miracles in this early section, one nature miracle is recorded, that of the stilling of the storm (Mt 8:23-27; Mk 4:35-41; Lk 8:22-25). This miracle focused both on the lack of faith in the disciples and the mysterious power of the presence of Jesus.

The Reaction to Jesus by His Contemporaries

In the early stages of his ministry, Jesus was very popular with the ordinary people. There are several notices to this effect (Mt 4:23-25; Mk 3:7-8). This popularity showed no appreciation of the spiritual purpose of Jesus’ mission (Lk 13:17). Nevertheless, it stands in stark contrast to the nit-picking opposition of the religious leaders, who even plotted to kill Jesus in the early period of his ministry (Mk 3:6).

Jesus and the religious leaders often clashed over the observance of the Sabbath (Mt 12:1-14; Lk 13:10-17; Jn 5:9-18). Jesus adopted a more liberal view than the rigid and often illogical interpretation of some of his religious contemporaries—as in the instances when he was criticized for healing on the Sabbath even though the Jewish law allowed the rescuing of trapped animals on the Sabbath (Mt 12:11; Lk 13:15). To the Pharisaic mind, Jesus was a lawbreaker. The Pharisees feared that it would undermine their authority if his teaching were permitted to permeate popular opinion.

Preparing the Twelve

The synoptic Gospels supply lists of the names of the 12 apostles (Mt 10:2-4; Mk 3:16-19; Lk 6:14-16). Both Matthew and Mark name them in the context of their exercising authority over evil spirits, thereby showing that these men were being called to enter the same spiritual conflict as Jesus.

The synoptic Gospels also give details of the instructions Jesus gave to these disciples before sending them to minister in Israel (Mt 10:5-42; Mk 6:7-13; Lk 9:1-6). Matthew included material in his discourse that appears in a different context in Mark and Luke, but the discourse still shows the concern of Jesus to prepare his disciples for their future work. They were to proclaim the kingdom as he had done, but they were not to suppose that all would respond to it. They were warned about coming hostility and even persecution. It is important to note that Jesus warned his disciples against encumbering themselves with material possessions. Although the instructions given related immediately to a ministry tour, he was laying the foundation for the future work of the church.

The Relationship between Jesus and John the Baptist

For a while there were parallel preaching and parallel baptisms by John the Baptist with his followers and Jesus with his disciples (Jn 4:1-2). After John the Baptist was imprisoned by Herod because of his uncompromising condemnation of Herod’s marriage to Herodias, his brother’s wife (Mt 14:3-4), John began to have doubts about Jesus (Mt 11:1-19; Lk 7:18-35). He may have been expecting Jesus, if he really was the Messiah, to come to his rescue. When John sent his disciples to Jesus to express his doubts, Jesus took the opportunity to tell the crowds of the greatness of John the Baptist. He said there was none born of women who was greater than John.

Various Controversies

Jesus did not hesitate to confront his contemporaries on issues that involved moral or religious questions. The controversy recorded in John’s Gospel concerning the keeping of the Sabbath that arose when a lame man was healed on that day (Jn 5:1-18) shows once again that ritual observance of the Sabbath was regarded as of greater importance than a compassionate concern for the physical welfare of the lame man. This was typical of the Jewish approach and led at once to a persecuting attitude toward Jesus, particularly because he claimed to be doing the work of God.

A similar conflict arose after Jesus’ disciples had plucked grain in the fields on the Sabbath day (Mt 12:1-8). The Pharisees assumed that this act constituted work and saw it as a sufficient reason to plot how to destroy Jesus. After this event, he healed a paralytic on the same Sabbath day (vv 9-14). The Jewish leaders clearly regarded him as a direct threat to their position among the people.

The rising opposition did not deter Jesus from further healings (Mt 12:15-32), which Matthew depicts as the fulfillment of Scripture. But when Jesus healed a blind and mute demoniac, the Pharisees charged him with casting out demons by Beelzebub, the prince of the demons. Jesus told them that to blaspheme the Holy Spirit was an unforgivable sin. This incident not only brings out the perversity of the religious leaders but also shows that the ministry of Jesus was under the direct control of the Spirit. Other notable miracles were the healing of the centurion’s servant, as recorded by Luke (Lk 7:1-10), and the raising from the dead of the widow’s son at Nain (vv 11-17). The former of these is notable because of the remarkable faith of a Gentile.

Another example of the Pharisees’ criticism was when Jesus attended a meal in Simon the Pharisee’s house (Lk 7:36-50). His host had not provided for the usual courtesies toward guests and yet was critical of Jesus for allowing an immoral woman to wash his feet with tears, dry them with her hair, and anoint them with ointment. There is no doubt that most of Simon’s colleagues would have shared his reaction, but Jesus did not stop the woman because he knew that the motive impelling her to do it was love. He told Simon a parable to press home his point.

John records two visits by Jesus to Jerusalem. These are difficult to date, but they probably occurred during the early period of the ministry. He attended the Feast of Tabernacles (Jn 7:2) and the Feast of Dedication (10:22). At these times Jesus taught in the temple area and entered into dialogue with the religious leaders. The chief priests became alarmed at his presence and sent officers to arrest him (7:32). They were unable to do so; instead, they themselves were captivated by his teachings. More discussions with the Jewish leaders followed. They charged Jesus with being demon-possessed (8:48). Both in this case and in the event of the healing of the blind man (ch 9), the hostility of the Jewish leaders to Jesus surfaces. When Jesus spoke of himself as the Shepherd, his teaching again raised the anger of his Jewish hearers, who took up stones to kill him (10:31).

Teaching in Parables

Matthew’s Gospel gives a sample of a continuous discourse by Jesus (Mt 5:1–7:29), but Jesus more often spoke in parables. Matthew collected into a group some of the parables that concern the theme of the kingdom (ch 13). Luke tends to preserve parables of a different kind that are not specially linked to the kingdom. Mark has the least number of parables among the synoptic Gospels, but his writing shows little interest in Jesus as a teacher. John does not relate any parables, although he does preserve two allegories—the Sheepfold and the Vine—which could be regarded as extended parables. The parable was a form of teaching particularly characteristic of Jesus. In addition, Jesus interspersed even his discourses with metaphors akin to the parabolic form. The parable was valuable because it could stimulate thought and challenge the hearer. This is because the form of the parable is easy to retain in the mind. Jesus did not speak in parables in order to obscure his meaning. This would be contrary to all that he aimed to do through his work and teaching.

Significant Events in Galilee

In Nazareth there was a striking instance of the unwillingness to respond to the ministry of Jesus. The people of his hometown proved so hostile that he could perform very few miracles there (Mt 13:53-58; Mk 6:1-6). This incident is important because it shows that faith was especially necessary for people to receive his healing miracles.

The one miracle performed by Jesus that all four Evangelists describe is the feeding of the 5,000 (Mt 14:13-21; Mk 6:30-44; Lk 9:10-17; Jn 6:1-15). This occasion shows the great popularity of Jesus at this stage of his ministry. It also reveals that he was not unmindful of the physical needs of people. After this miracle, some wanted to make Jesus king. This casts considerable light on their real motives. They were more concerned with material and political expediency than with spiritual truth. This is why Jesus immediately withdrew from them. When the people found him the next day, he proceeded to instruct them about the spiritual bread that comes from heaven (Jn 6:25-40).

At this point in John’s Gospel, Jesus is often seen in dialogue with his opponents. This style of teaching is different from the synoptic parables but familiar in Jewish-style debate. Many of the people found the spiritual themes in the teaching of Jesus too difficult to accept and consequently ceased to be his disciples (Jn 6:51-52, 60, 66). This incident demonstrates the unique challenge presented by Jesus and his teaching. Another miracle closely linked with this is when Jesus walked on the water, demonstrating his power in the natural world. Many have sought to rationalize the event by supposing that Jesus was really walking on the shore, and that the disciples did not realize this in the haze. But this miracle is no more extraordinary than the massive multiplication of loaves and fishes, nor is it inconceivable if the miracle worker was all that he claimed to be.

Leaving Northern Galilee

Jesus spent a brief time in the region of Tyre and Sidon, where he performed further healings and made it clear that his main mission was to the house of Israel (Mt 15:21-28). He then moved on to Caesarea Philippi; this was the turning point of his ministry (Mt 16:13-20; Mk 8:27-38; Lk 9:18-27). It was there that Jesus asked his disciples: “Who do people say the Son of Man is?” This caused Peter to confess: “You are the Christ, the Son of the living God.” This impressive confession led Jesus to promise that he would build his church on “this rock.” There has been much discussion about the meaning of this saying. It is open to some doubt whether Jesus intended to build his church on Peter, on his confession, or on Peter making the confession. Historically, Peter was the instrument God used for the entrance into the church of both Jews and Gentiles (Acts 2, 10). There is no doubt about Jesus’ intention to found a church, since the word occurs again in Matthew 18:17. Despite the glorious revelation of Jesus on this occasion, he took it as an opportunity to begin to inform his disciples of his death and resurrection (Mt 16:21-23).

This revelation of Jesus was considerably reinforced by the event known as the Transfiguration, when Jesus was transformed in the presence of three of his disciples (Mt 17:1-8). It was natural for them to want to keep this glorious vision of Jesus for themselves, but the vision vanished as rapidly as it came. Its purpose was evidently to show the three leading disciples something of the nature of Jesus, which was obscured by his normal human form. A further feature of the vision was the appearance with Jesus of Moses and Elijah, representatives of the Law and the Prophets.

After the Transfiguration, Jesus made two predictions concerning his approaching death. These announcements were a total perplexity to the disciples. In Matthew 16, when Jesus mentioned his death, Peter attempted to rebuke Jesus and was rebuked by Jesus in kind. When Jesus mentioned his death again in chapter 17, Matthew noted that the disciples were greatly distressed (Mt 17:23), while Mark and Luke mentioned the disciples’ lack of understanding (Mk 9:32; Lk 9:45). Jesus was approaching the cross with no support from those closest to him. It is not surprising that when the hour arrived they all forsook him.

After the Transfiguration revealed that Jesus was greater than Moses and Elijah and in fact was the beloved Son of God, he was asked to pay the temple tax (Mt 17:24-27). This incident illustrates the attitude of Jesus toward the authorities and practical responsibilities. He paid the tax, although he did not acknowledge any obligation to do so. The method of payment was extraordinary, for it involved the miracle of the coin in the fish. But the greater importance of the incident is the light it throws on Jesus’ independence from the Jewish law.

Luke devotes more than half his Gospel to the period that begins with Jesus leaving Galilee and ends with his death and resurrection in Jerusalem. In this section of his Gospel, Luke introduces a great deal of material that does not occur elsewhere. We can do no more than summarize some of the more striking items that throw light on the life of Jesus.

In addition to the mission of the Twelve, Luke records the mission of the Seventy (or Seventy-two—see Lk 10:17-20). Special parables are recorded by Luke in this section—the Good Samaritan (vv 29-37), the lost sheep (15:3-7), the lost coin (vv 8-10), and the prodigal son (vv 11-32). As Jesus moved toward Jerusalem, he was concerned with developing the spiritual life of his disciples. He was mindful of the fact that he would not be with them long and wished to prepare them for the future. He taught them about prayer (11:1-13), the Father’s care for them (12:13-34), and preparation for the coming of the Son of Man (vv 35-56).

On the Way to Jerusalem

On the approach to Jerusalem, Jesus visited both Jericho and Bethany. At Jericho he healed Bartimaeus (Lk 18:35-43) and had a fruitful encounter with Zacchaeus, who reformed his ways as a tax collector (19:1-10). Bethany was the home of Mary, Martha, and their brother, Lazarus, whom Jesus had raised from the dead (Jn 11). Jesus spent his remaining days in Jerusalem but returned each night to stay at Simon the Leper’s house in Bethany in the presence of those who loved him (Mt 26:6). It was there that a woman anointed his body with costly ointment. This was a controversial and prophetic act preparing Jesus for his burial and enhancing the gospel with loving consecration (vv 6-13).

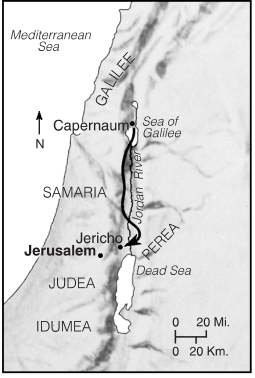

Jesus Travels toward Jerusalem

Jesus left Galilee for the last time, heading toward Jerusalem and death. He again crossed the Jordan, spending some time in Perea before going on to Jericho.

The Final Days in Jerusalem

All four Gospels relate the entry of Jesus into Jerusalem (Mt 21:1-11; Mk 11:1-10; Lk 19:29-38; Jn 12:12-15). At this time multitudes greeted Jesus with praises acclaiming him as their king. This welcome stands in stark contrast with the crowd’s later cry for his crucifixion. In fact, it was the second crowd that was doing God’s bidding, since Jesus had not come to Jerusalem to reign but to die.

The synoptic Gospels place the cleansing of the temple as the first main event following Jesus’ entry into the city (Mt 21:12-13; Mk 11:15-17; Lk 19:45-46). The clouds of opposition had been thickening, but the audacity of Jesus in clearing out the money changers from the temple area was too much for the authorities (Mk 11:18; Lk 19:47). The die was cast and the Crucifixion loomed closer.

It was during this period that further controversies developed between Jesus and the Pharisees and Sadducees (Mt 21:23–22:45). In several cases trick questions were posed in order to trap Jesus, but with consummate skill he turned their questions against them. His opposers eventually reached the point where they dared not ask him any more questions (22:46).

Nearing his final hour, Jesus took the opportunity to instruct his disciples about future events, especially the end of the world. He reiterated the certainty of his return and mentioned various signs that would precede that coming (Mt 24–25; Mk 13; Lk 21). The purpose of this teaching was to provide a challenge to the disciples to be watchful (Mt 25:13) and diligent (vv 14-30). This section prepares the way for the events of the arrest, the trial, the scourging, and the cross carrying and crucifixion that followed soon after. But first we must note the importance of the Last Supper.

When Jesus sat at the table with his disciples on the night before he died, he wished to give them a simple means by which the significance of his death could be grasped (Mt 26:26-30; Mk 14:22-25; Lk 22:19-20; 1 Cor 11:23-26). The use of the bread and wine for this purpose was a happy choice because they were basic elements in everyday life. Through this symbolic significance Jesus gave an interpretation of his approaching death—his body broken and his blood poured out for others. It was necessary for Jesus to provide this reminder that his sacrificial death would seal a completely new covenant. It was to be an authentic memorial to prevent the church from losing sight of the centrality of the cross.

John’s Gospel does not relate the institution of the Last Supper. Nevertheless, it does record a significant act in which Jesus washed the feet of the disciples as an example of humility (Jn 13:1-20). He impressed on the disciples the principle of service to others. John follows this display of humility with a series of teachings Jesus gave on the eve of the Passion (chs 14–16). The most important feature of this teaching was the promise of the coming of the Holy Spirit to the disciples after Jesus had gone. Even with his mind occupied by thoughts of approaching death, Jesus showed himself more concerned about his disciples than about himself. This is evident in the prayer of Jesus in John 17. All the Evangelists refer in advance to the betrayal by Judas (Mt 26:21-25; Mk 14:18-21; Lk 22:21-23; Jn 13:21-30), which prepares readers for the final stages of the way of Jesus to the cross.

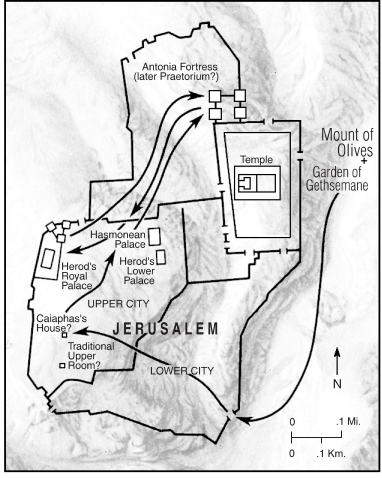

The Betrayal and Arrest

There is a sense in which the whole gospel story has been working up to a climax of rejection. The various outbursts of popular support were soon over and the determined opposition emerged as seemingly in control. In John’s Gospel the sense of approaching climax is expressed in terms of “his hour” (Jn 13:1). When this at length comes, the betrayal and arrest are seen as part of a larger plan. From the upper room where the Last Supper was eaten, Jesus went straight to the Garden of Gethsemane (Mt 26:36-46; Mk 14:32-42; Lk 22:40-46), where he prayed to his Father with deep intensity and agony. In this we see part of what it cost Jesus to identify himself with man’s need. He prayed for the cup of suffering to pass from him but at the same time submitted to the Father’s will. The three disciples he took with him all fell asleep, while one of his other disciples, having betrayed his master, appeared at the gates at the head of the group who had come to arrest him. At the moment of confrontation with Judas, Jesus exhibits an amazing dignity when he addressed the betrayer as his “friend” (Mt 26:50). He offered no resistance when he was arrested and chided the crowd of people for their swords and clubs (v 55).

The Trial

Jesus was first taken to the house of Annas, one of the high priests, for a preliminary examination (Jn 18:13). During his trial, he was scorned by his enemies, and one of his disciples, Peter, denied him three times (Mt 26:69-75; Mk 14:66-72; Lk 22:54-62; Jn 18:15-27), as Jesus predicted he would (Mt 26:34; Mk 14:30; Jn 13:38). The official trial before the Sanhedrin was presided over by Caiaphas, who was nonplussed when Jesus at first refused to speak. At length Jesus predicted that the Son of Man would come on the clouds of heaven; this was enough to make the high priest charge him with blasphemy (Mk 14:62-64). Although he was spat upon and his face was struck, Jesus remained calm and dignified. He showed how much greater he was than those who were treating him with contempt.

The further examinations before Pilate (Mt 27:1-2; Mk 15:1; Lk 23:1; Jn 18:28) and Herod (Lk 23:7-12) were no better examples of impartial justice. Again Jesus did not answer when asked about the charges before either Pilate (Mt 27:14) or Herod (Lk 23:9). He remained majestically silent, except to make a comment to Pilate about the true nature of his kingship (Jn 18:33-38). The pathetic governor declared Jesus innocent, offered the crowds the release of either Jesus or Barabbas, and then publicly disclaimed responsibility by washing his hands. Pilate then cruelly scourged Jesus and handed him over to be crucified. This judge has ever since been judged by the prisoner.

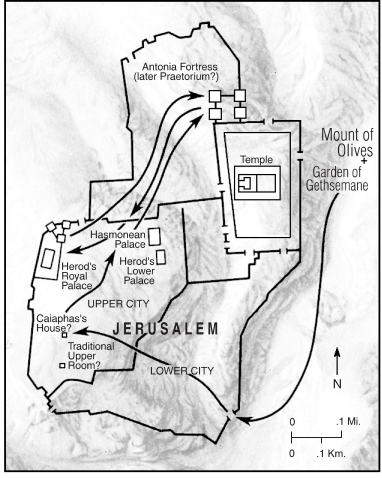

The Last Evening

After Judas singled Jesus out for arrest, the mob took Jesus first to Annas and then to Caiaphas, the high priest. This trial, a mockery of justice, convened at daybreak and ended with their decision to kill him, but the Jews needed Rome’s permission for the death sentence. Jesus was taken to Pilate (who was probably in the Praetorium), then to Herod (Lk 23:5-12), and back to Pilate, who sentenced him to die.

The Crucifixion

The reader of this scene cannot help but see man’s inhumanity to man—even the man of all men, Jesus Christ. The soldiers’ ribald mockery of Jesus (Mt 27:27-30), mixing a royal robe with a hurtful crown of thorns (Mk 15:17), compelling a passerby to carry the cross (Lk 23:26), the cruel procedure of nailing Jesus to the cross, the callous casting of lots for his garment (Jn 19:23-24), and the scornful challenge to him to use his power to escape (Mt 27:40-44)—all expose the cruelty of Jesus opponents. But against this is Jesus’ concern about the repentant criminal who was crucified with him (Lk 23:39-43), his concern for his mother (Jn 19:25-27), his prayer for forgiveness for those responsible for the Crucifixion (Lk 23:34), and his final triumphant cry (Mk 15:37)—all of which show a nobility of mind that contrasted strongly with the meanness of those about him. A few observers showed a better appreciation, like the centurion who was convinced of Jesus’ innocence (Mk 15:39) and the women who followed him and stood at a distance (Mt 27:55-56). There was one dark moment, as far as Jesus was concerned—his forsaken cry, which quickly passed (Mk 15:34). There was an accompanying darkness and an earthquake, as if nature itself were acknowledging the significance of the event. Even the temple veil was torn in two, as if it had no longer any right to bar the way into the Holy of Holies (Mt 27:51).

The Burial, Resurrection, and Ascension

Jesus’ body was placed in a tomb that belonged to Joseph of Arimathea, who was assisted by Nicodemus in laying the body to rest (Mt 27:57-60; Jn 19:39). But the tomb played only an incidental part in the resurrection. The Evangelists concentrate on the appearances of Jesus not only on the day of resurrection but also subsequently. The disciples were convinced that Jesus was alive. Some, like Thomas, had doubts to overcome (Jn 20:24-29). Others, like John, were more ready to believe when they saw the empty tomb (vv 2-10). It is not without significance that the first to see the risen Lord was a woman, Mary Magdalene (Mt 27:61; 28:1, 5-9), whose presence at the cross put to shame those disciples who had run away (Mt 26:56; Jn 19:25).

We may note that in his glorified, risen state Jesus was in a human form, although he was not at once recognized (Jn 20:15-16). There was a definite continuity with the Jesus the disciples had known. The appearances were occasions of both joy and instruction (cf. Lk 24:44 and Acts 1:3). The resurrection, in fact, had transformed the Crucifixion from a tragedy into a triumph. Forty days after his resurrection, Jesus ascended into heaven to join his Father in glory (Lk 24:51; Jn 20:17; Acts 1:9-11).