Open Bible Data Home About News OET Key

A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W XY Z

Tyndale Open Bible Dictionary

Intro ← Index → ©

PETER, First Letter of

First of two general epistles authored by Peter.

Preview

• Author

• Destination, Origin, Date

• Background

• Purpose and Theological Teaching

• Content

Author

The author says he is the apostle Peter (1 Pt 1:1), a witness of Christ’s sufferings (5:1)—thus one of the original apostles chosen by Jesus (Mk 3:14-19) as an authoritative spokesman. Also known as Simon and Cephas, Peter probably saw and felt Jesus’ last hours of suffering more keenly than any of the other apostles (14:54) because he had denied Jesus three times (vv 66-72). In 1 Peter the sufferings of Jesus are mentioned at least four times (1 Pt 1:11; 2:23; 4:1; 5:1).

Peter was known as the apostle to the Jews, just as Paul was the apostle to the Gentiles (Gal 2:7). Since Peter was a traveling missionary (1 Cor 1:12; 9:5), he could have actually visited the Asia Minor churches to whom this letter was sent.

That Peter had been with Jesus during his earthly ministry may help account for the strong influence of Jesus’ teaching in 1 Peter. Except for James, 1 Peter probably echoes more of Jesus’ words than any other NT letter. The chart below presents similarities between Peter’s words and Jesus’ words in the Gospels:

Some scholars think the Greek of this letter is too good to have been written by a former fisherman whose native language was Aramaic; that the doctrine is too much like Paul’s to have been written by an apostle whose position was different from Paul’s; and that someone wrote the letter after Peter’s death and used his name to give apostolic weight to it.

Other scholars answer that if the author wanted to give authority to a letter whose teaching resembles Paul’s, he would have used Paul’s name, not Peter’s; that most Galileans probably learned Greek as well as Aramaic early in life; and that there is no evidence that the teaching of Peter and Paul fundamentally differed. When Paul rebuked Peter (Gal 2:11-14), it was due to a temporary lapse in conduct, not a basic disagreement in teaching. Besides, some key doctrines of Paul are missing from 1 Peter (e.g., justification), and those similar to Paul’s were the common possession of all the early churches. We may reasonably conclude that the apostle Peter authored this letter. However, it seems quite clear that Silas (otherwise know as Silvanus) helped Peter write this epistle (1 Pt 5:12), which means (1) he functioned as an amanuensis (secretary) for Peter, (2) he translated Peter’s letter (from Aramaic to Greek) as Peter dictated it, or (3) he composed a letter based on Peter’s thoughts.

Destination, Origin, Date

The people to whom 1 Peter is addressed lived in Pontus, Galatia, Cappadocia, Asia, and Bithynia. These Roman provinces covered all but the southernmost part of Asia Minor, the bulk of modern Turkey.

Christianity may have been brought back by pilgrim Jews converted in Jerusalem on the day of Pentecost (cf. Acts 2:9). More likely, these churches included some founded by Paul on his first and second missionary journeys, and others by unknown missionaries. Peter does not explicitly include himself among “those who preached to you” (1 Pt 1:12).

Whether the readers were Christian Jews or converted pagan Gentiles is not known. First Peter 1:1 reads: “to God’s chosen people who are living as foreigners in the lands of Pontus, Galatia, Cappadocia, the province of Asia, and Bithynia” (NLT). That the readers are in some sense exiles is confirmed by 1:17 and 2:11. These verses could refer to a literal exile of Jews outside of Palestine or to a spiritual exile of all believers on earth because their true home is in heaven. No one denies that there was (and is) a literal Jewish dispersion (Diaspora). Peter, viewing the church as the true Israel (cf. Rom 2:29; Gal 6:16; Phil 3:3), may simply have transferred the language of exile from the nation Israel onto the church. The phrase used by Peter in 1 Peter 2:11 is almost identical to the one in Hebrews 11:13 (cf. Gn 23:4; Ps 39:12).

Against the view that construes the dispersion of 1 Peter 1:1 as Christians (Jew and Gentile), rather than Jews only, one may argue that Peter was specifically the apostle to the Jews (Gal 2:7) and that the use of so much OT in 1 Peter demands a Jewish readership. But there is evidence that Peter did not restrict his ministry to Jews (1 Cor 1:12; Gal 2:12), and the use of the OT is not surprising even if the readers were not Jews, because so many Gentile God-fearers (like Cornelius, Acts 10:2) were familiar with the OT.

Whether the readers were Jews or mainly Gentiles is decided by several texts that reflect the pagan background of the readers. Peter says in 1 Peter 2:10 that his readers were once “not a people,” a reference to Hosea 2:23 (cf. Rom 9:25). Then in 1 Peter 4:3 Peter describes their past “immorality and lust, their feasting and drunkenness and wild parties, and their terrible worship of idols” (NLT). This does not describe unbelieving Jews, whose problem was not gross immorality but hypocrisy and legalism. Thus the recipients of this letter must have included many Gentile Christians in Asia Minor, characterized as aliens and strangers in the world.

Most scholars think 1 Peter was written from Rome. The clue is found in 5:13: “She who is in Babylon, chosen together with you, sends you her greetings” (niv). Babylon (which had come to symbolize a big, powerful, evil city) was substituted as a kind of code name for Rome in much early Christian literature (e.g., Rv 14:8; 16:19; 17:5; 18:2, 10, 21; cf. Sibyllene 5:143, 159).

The date of 1 Peter is probably AD 64 or 65 (see next section).

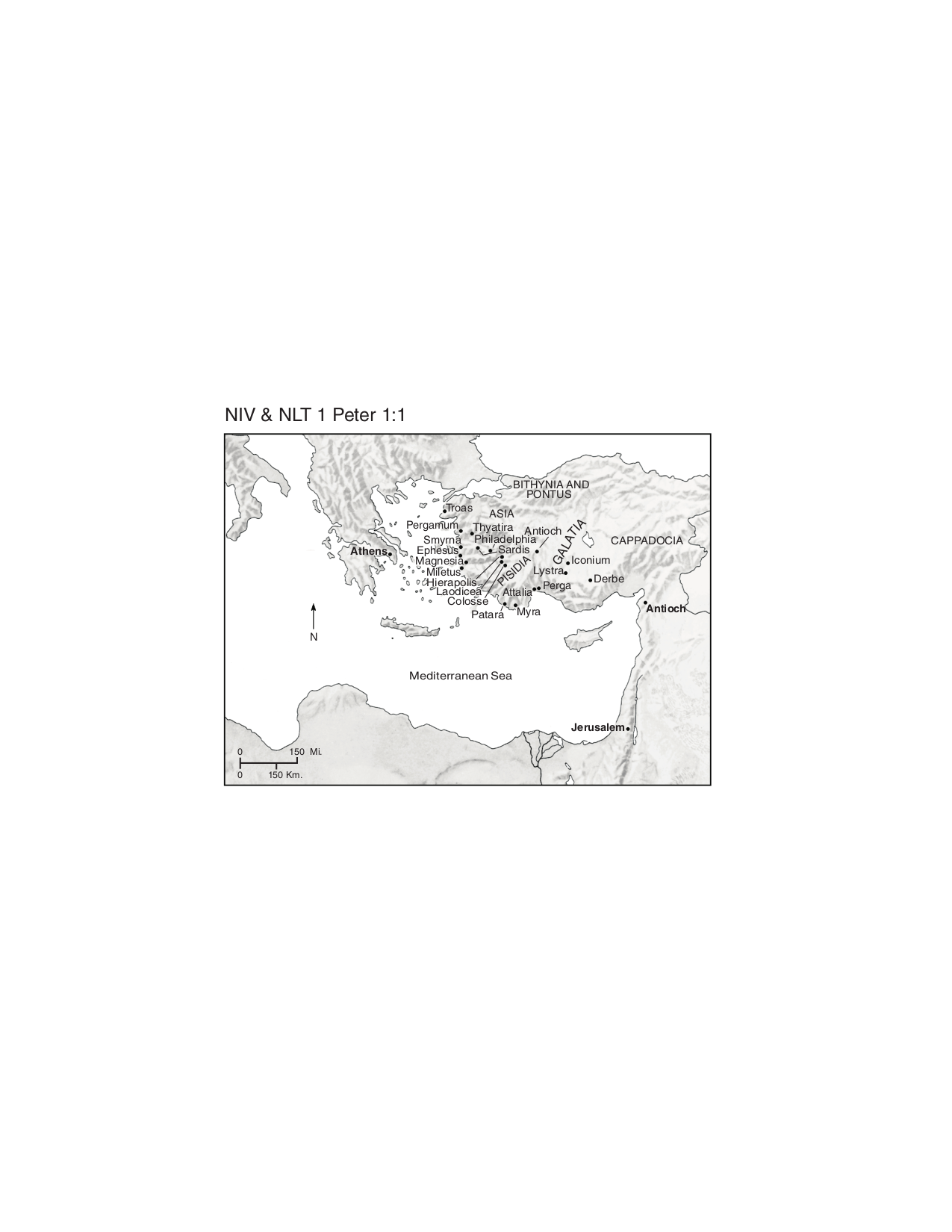

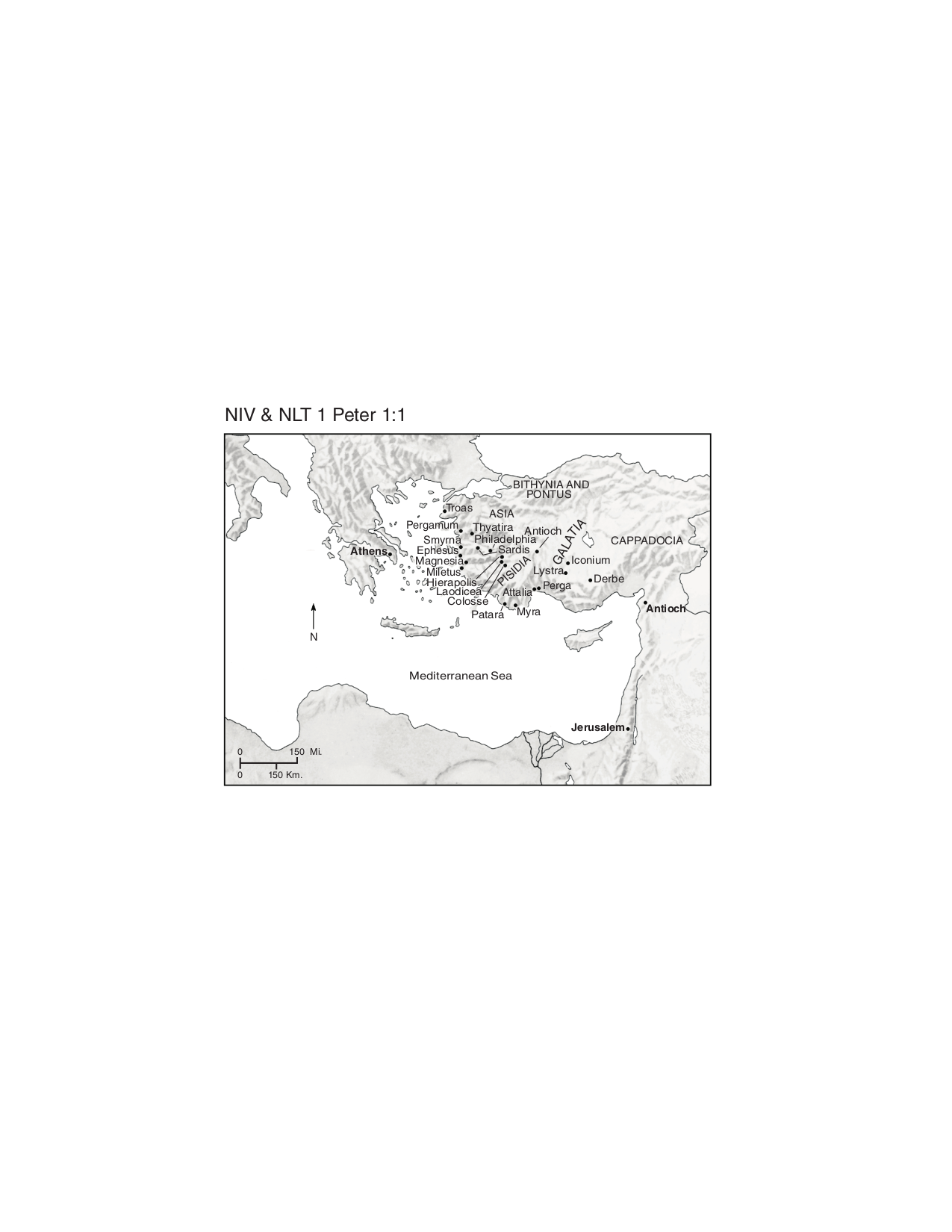

The Churches of Peter’s First Letter

Peter addressed his letter to the churches located throughtout Bithynia, Pontus, Asia, Galatia, and Cappadocia. Paul had evangelized many of these areas; other areas had churches that were begun by the Jews who were in Jerusalem on the day of Pentecost and heard Peter’s powerful sermon (see Acts 2:9-11).

Background

While other NT writings refer now and then to Christian suffering, 1 Peter is preoccupied with it. How Christians should conduct themselves when abused is often discussed (1 Pt 1:3-7; 2:12, 20-23; 3:13-17; 4:12-19; 5:9-10). Official state persecution cannot be clearly affirmed; abuses seem to be the common lot of all Christians everywhere (5:9). Cruel masters may sometimes abuse their Christian servants (2:18-20); Christian wives may have to endure harsh, unbelieving husbands (3:1-6); and in general, people are on the lookout to revile Christians as wrongdoers (2:12; 3:9, 16; 4:15-16).

Even though no official state persecution is in view, the letter apparently indicates that there is something worse on the horizon (4:12-19). Peter seems to sense that the present tension between believers and their society could flare into something much worse.

Early church tradition says that Peter was crucified in Rome during Nero’s persecution, and there is no good reason to doubt it. Moreover, since 1 Peter was written from Rome, and since 4:12 and 17 imply an impending crisis like the one that struck the Christians in Rome in AD 65, we may suppose that this letter was written not long before Nero began to oppress the Christians in Rome. According to the historian Tacitus, Nero blamed the Christians for burning Rome, in order to squelch the rumor that he himself had done it (so that he could build a greater city). His relentless persecution of Christians had not yet broken out when 1 Peter was written (cf. 2:14; 3:13), but Peter may have seen it coming and may have wanted to prepare the churches outside Rome, should the holocaust reach them, too. Nero’s persecution apparently did not affect the Christians in the provinces outside Rome, but that does not diminish the value of Peter’s letter, because mostly it deals with how Christians should relate to their society and how they should respond when abuse and suffering come.

If this is a correct picture of the background of 1 Peter, its date would be the early to mid 60s, since the fire of Rome broke out on July 19, AD 64, and the persecution occurred later that year or in the spring of 65.

Purpose and Theological Teaching

The main purpose of 1 Peter is to exhort Christians to conduct themselves properly among the community of believers (3:8; 5:1-7), but especially in non-Christian society (2:12), testifying clearly to their hope in Christ (3:1, 15) for God’s glory. The letter aims to help Christians understand and endure the abuses that often come from relationships with non-Christians (1:6-7; 2:12, 18-25; 3:9, 14-17; 4:1-5, 12-19; 5:8-10).

Peter’s exhortation is based on the good news of God’s salvation through the death, resurrection, and second coming of Christ. God is merciful (1:3; 2:10), “the God of all grace” (4:10; 5:12), and there is hope in grace’s ultimate display at Christ’s coming (1:13). God foreknew and determined (1:2, 20; 2:8) a plan of redemption by which to create a holy people for his own possession (2:9-10). Accordingly, Christ was sent into the world to accomplish this redemption for the sake of God’s elect (1:20). Although he was “chosen and precious” to God, he was “rejected by men” (2:4) who did not believe him (v 7). But his sufferings (1:11; 4:1, 13; 5:1) were not a meaningless tragedy; they were for the sake of his people (2:21, 24; 3:18), to redeem them with his precious blood from their empty way of life (1:18-19).

Put to death in the flesh, he was “made alive by the Spirit” (3:18), raised from the dead and glorified (1:21; 2:7), and holds the place of authority at God’s right hand (3:22). Further still, we must try to explain the link between the good news of God’s saving activity and our good conduct. The good news must be proclaimed if it is to change anybody’s life. This proclamation happens in the power of God’s Holy Spirit (1:12). It is not merely a “newscast” but is “the living and abiding word of God” (1:23; cf. 4:11), by which God calls his people into being and summons them “out of darkness and into his wonderful light” (2:9; cf. 1:15), “to his eternal glory in Christ” (5:10). This change is described in 1 Peter as a “new birth” (1:3, 23); what distinguishes a newborn person is the “living hope” that he has in Christ (1:3, 13).

This hope, grounded in Christ’s resurrection and his sure return, transforms behavior (1:13-15). No longer will we have to seek satisfaction and fulfillment in harmful, unloving ways, but rather by entrusting our souls to a faithful Creator (4:19; 5:7), we can endure unjust suffering patiently (2:20), not return evil for evil (3:9), and seek to extend the mercy of God to others in doing good (2:12, 15; 3:11, 16; 4:19).

Lively Christian hope does not lead us out of non-Christian society but rather changes our behavior in it. Christians are addressed as citizens of the state (2:13-17), as slaves of cruel masters (vv 18-25), and as wives of unbelieving husbands (3:1-6). By living as new and hopeful persons in the institutions of society, others see our good deeds and give glory to our Father in heaven (2:12; cf. Mt 5:16).

Content

1:1–2

This section describes God’s election of his people, which is often translated using three prepositional phrases.

First, it is “according to the foreknowledge of God” (niv). This means more than God’s knowing ahead of time whom he would elect. As in 1:20, foreknowledge probably also includes God’s purpose (cf. Am 3:2; Acts 2:23; Rom 8:28-30; 11:2; 1 Cor 8:3; Gal 4:9).

Second, the election is “by the sanctifying work of the Spirit” (nasb). Election involves the Spirit’s effectual work in making a person obedient to the gospel (see Rom 1:5). In Ephesians 1:4 election is described as “before the foundation of the world” (KJB).

Third, our election is “for obedience to Jesus Christ and for sprinkling with his blood” (rsv). The latter probably refers to the moral effect of Christ’s death in purifying our conscience and our behavior as we trust in him (see Heb 9:13-14).

Thus, the elect people of God have their origin in the eternal, purposed foreknowledge of God; owe their call and conversion to the work of the Holy Spirit; and have as their goal in life obedience to God (cf. 1 Pt 1:14).

1:3-12

This section describes how tremendously valuable salvation is—a vast inheritance, absolutely perfect, never diminishing in beauty or worth (v 4), the goal of our faith (v 9), the basis of inexpressible joy (vv 6-8). Searched into and desired by the holy prophets of old, it is so amazing that even angels desire to peer into it (vv 10-12).

It originates in the great mercy of God and was made available to people through the resurrection of Jesus from the dead (v 3). Even though a future inheritance is ready to be revealed in the last time (v 5), it offers many present spiritual benefits for those who trust in Christ. One of them is the promise of God’s present power to cause the believer to persevere in faith (v 5). This does not mean Christians escape hardship; it may be necessary that they suffer (v 6). If so, they should not grumble but see suffering as a refining fire for their good, because it burns away false dependencies and leaves only the pure gold of genuine faith (v 7). So suffering may be an important preparation for the full experience of salvation, since it is faith alone that will be blessed in the end.

Faith is not the same as sight, for believers have never seen Jesus, yet they trust him and love him (v 8). There are good grounds for hope (3:15), founded mainly on the resurrection of Jesus (1:3)—a real historical event.

1:13-25

Peter now gives a command: hope fully in the grace coming to you at the revelation of Christ (v 13), and lead a new life of obedience to God (vv 14-15). Hope is an intense desire for something and a confidence that it will come. So Peter was commanding the churches to desire Christ strongly and be assured of his glory and his coming. Thus, believers must use their minds and keep clearheaded (sober) about what is truly valuable in life (v 13). Full hope in Christ always results in holiness of life. If we delight in being God’s children (v 14), we will surely imitate our Father (vv 15-16; cf. Lv 19:2).

But there is another motivation for good conduct: fear of God, who judges each person according to his or her works (1 Pt 1:17). While Peter motivates with fear, he also assures us that we have been redeemed from our futile conduct with the precious blood of Christ (vv 18-19). We are saved by faith, not by good works. Probably Peter means us to fear God’s displeasure with unbelief. When the letter says he will judge our works, it probably means that he will look for evidences of obedient, loving conduct, which is the sure sign of hope and faith. If we are lacking in this, fear of his judgment should drive us back to God’s mercy, where we can have peace and joy, which in turn lead to love.

This love is commanded toward believers in verse 22. Hope is not mentioned in verses 22-25, but it is implied when Peter says we are born anew through the abiding Word of God. Since “the word of the Lord abides forever” (v 25 = Is 40:6-8), those whose life depends on it will abide forever.

2:1-10

This passage is filled with OT quotations and imagery, as shown in the following chart:

Verses 9 and 10 indicate that Peter considered the Christian church a new Israel. He probably saw the experience of the church in the world as that of an exile like the Jews in Babylonian exile (1:1, 17; 2:11), and considered conversion as a kind of exodus out of the darkness of an old futile life into God’s light, like the Jewish exodus out of Egypt.

Verses 6-8 show that Jesus is a precious jewel for some but a stumbling stone for unbelievers. Behind that stands God’s inscrutable predestination (v 8). Those who trust him are chosen (v 9; cf. 1:1) as a royal priesthood (see below on 2:5), as a nation having God’s own holy character (cf. 1:14-15), and as a people cherished as God’s special possession. All of this is not due to our merit but to God’s mercy (v 10).

Verses 1-3 are again a command—to desire the kindness of Christ that we have tasted through the milk of the Word and so to grow stronger in faith or to hope fully in the grace of Christ.

Verses 4-5 portray a complex, mixed metaphor that pictures Christ as a living stone and the church both as a spiritual house of stones and as a priesthood. The church is, on the one hand, a dwelling place for God (cf. 1 Cor 3:16; Eph 2:21-22), and on the other, a group of ministers in that dwelling who offer God the sacrifices of obedience (cf. Rom 12:1-2).

2:11-12

This is the central concern of the letter. Since Christians are exiles in this world, they must not share the same desires as unbelievers. Such fleshly desires are ephemeral and destroy the soul that follows them. Instead, God’s new people should devote themselves to good deeds, even though people may slander them, for this will ultimately cause people to glorify God. The sequence, again, is changed desires, changed behavior, God glorified (cf. Mt 5:16).

2:13-17

Christians should show proper respect to everyone (vv 13-14). That Christ died for sinners is a very humbling truth that forbids Christians to be arrogant or to think that they do not owe others love (cf. Rom 13:8-10). Rather, they are adjured to count others better than themselves (Mk 10:44; Phil 2:3).

Peter declares, then, that believers should be subject to the king and to the civil authorities under him. They should positively devote themselves to doing good so that those who say Christianity makes no difference in life will be silenced.

However, subjection to the state is not absolute, for Christians are first and foremost slaves of God. It is out of freedom that they acknowledge the propriety of a God-ordained state to preserve orderly life. Because Christians serve God first, and the king is merely God’s creature, subjection to him is a subjection for the Lord’s sake, not the king’s sake.

2:18-25

Christian slaves have consciences oriented toward and shaped by God (v 19). They also have experienced his grace and are here told to rely on it by enduring unjust suffering patiently. They are not to strike back: they were called to live this way because Jesus suffered for them and because he suffered as an example. Verses 21-23 describe the example. Verses 24-25 describe Christ’s redemption and its effects. That is, Jesus not only modeled the life of nonretaliation but also enabled his followers to live this way by dying for them that they might live for righteousness (v 24). Only when Christians are secure and content in the hope Christ achieved for them can they have the freedom and inclination to follow his costly example. When believers are tempted to take vengeance into their own hands, they should recall that even Jesus entrusted himself to God, who judges justly (v 23; cf. Rom 12:19-20).

3:1-7

Here are six verses for wives and one for husbands. How shall a believing wife win her unbelieving husband (v 1)? Peter warns against preoccupation with making the body more attractive (v 3). Instead, he stresses the adornment of the heart with a meek and tranquil spirit (v 4), accompanied by pure, loving conduct (v 2), which may win the husband “without talk” (v 1). This is not a call to mindless subservience but to poise, to free and confident service in love. The wife is not to be afraid even of an abusive husband (v 6). But how? By following Sarah’s example of hoping in God (v 5). So it is again said that hope transforms life and enables believers to be subject to others. The wife is bound first to the Lord and only secondarily to her husband. Like the slave, the Christian wife will use her God-oriented conscience (2:16) to decide when, for Christ’s sake, she cannot follow the lead of her husband.

Husbands are admonished in verse 7 to bring their relationships to their wives into conformity with natural and revealed truth. The natural truth is that women are physically weaker. This does not mean that they are inferior mentally or emotionally. It is a simple statement of observed fact: women’s bodies are not as strong as men’s. In a culture without all kinds of automatic devices, physical strength was much more crucial for survival and comfort than it is today. So the man is urged to use his superior strength for the sake of his wife. The revealed truth is that the wife is an “equal partner in God’s gift of new life,” to be honored and respected.

3:8-12

This concludes the section 2:13–3:12 and admonishes the whole church first to love the brotherhood (3:8) and then to love the hostile outsider (vv 9-12). Verse 9 recalls Jesus’ behavior and his commands (Lk 6:27-36). Not only are Christians to endure abuse patiently (1 Pt 2:19-20), they are also to react positively and “bless” those who revile them (3:9). To bless means to wish them well and turn the wish into a prayer. Believers’ real desire for their enemies is that they be converted and come to share in the blessing that the Christian will inherit (vv 1, 9). Psalm 34:12-16 is brought in to support the logic of verse 9. If Christians want to inherit the blessing of salvation (1:4-5; 3:9), they must bless those who revile them. This does not mean they earn their salvation but that salvation is the goal of faith (1:9), and true faith always makes a person loving.

3:13-17

Generally speaking, when Christians do good, they will not be harmed for it (v 13). Nevertheless, it may be God’s will that Christians suffer for doing good (v 17) and that is far better than suffering for doing evil. It is better not only because they ought never do evil but also because they are “blessed” when they suffer for righteousness’ sake (v 14; cf. 4:14; Mt 5:10-12). So instead of being afraid of people, believers should fear displeasing Christ and be at peace in his faithfulness (cf. 1 Pt 3:14-15 with Is 8:12-13). Thus, their consciences will be clear and believers will be freed so that when they explain the reason for their hope, even their demeanor will bear witness to its truth (cf. 1 Pt 3:15 with 1:3). The Christians’ abusers may be put to shame (v 16) and be won over (3:1) and give glory to God (2:12).

3:18-22

Similar to 2:21-25 and 1:18-21, this unit affirms Peter’s call for patient suffering. Since Christ died once for all for mankind’s sins and thus freed everyone from guilt and opened a way into the fellowship of the merciful God, believers should be able to bear unjust suffering meekly. Refusing to bear undeserved suffering would be a mark of unbelief in the all-faithful Creator (4:19) who cares for his children and wants to bear their anxieties for them (5:7).

Just as in the days of Noah, only a few were saved (cf. 3:1, 20; 4:17), so now only a few were being saved in Peter’s hostile generation, through baptism (3:18-21). Peter defined very carefully in what sense he meant that baptism saves—not by the cleansing function of the water, but rather by the resurrection of Jesus Christ and the pledge of a good conscience toward God (v 21).

4:1-6

Christians should live according to the will of God (cf. 1:14; 2:1-2, 11-12, 15). This will mean a break with the behavior of their unbelieving friends and will probably result in being slandered (4:4). But this should not cause believers to avenge themselves, for God will take care of judgment (v 5).

Believers have this command (v 1): “So then, since Christ suffered physical pain, you must arm yourselves with the same attitude he had, and be ready to suffer, too. For if you are willing to suffer for Christ, you have decided to stop sinning” (NLT). Some have taken this to mean that through a process of suffering we are increasingly sanctified; however, if suffering here refers to dying (as the parallel with 3:18 and the “therefore” of 4:1 suggest), then probably verse 1 is to be understood along the lines of Romans 6:6, 10-11.

First Peter 4:6 is difficult. Some think it refers to the same preaching referred to in 3:19. Another, perhaps preferable, interpretation is that there is no preaching to the dead here but rather a preaching of the gospel to those who subsequently died. That is, those who heard the gospel, believed, and then died did not hear the gospel in vain. For the purpose of the preaching was that, while from a merely human standpoint these believers have been judged in the flesh (i.e., have died), from the divine standpoint they live in the Spirit. The purpose of verse 6 is thus a great encouragement to live by God’s will, even when former friends scorn the Christian hope by pointing out that even Christians die.

4:7-11

Activity among believers in the church is again the theme here. Peter saw contemporary events as the beginning of the end (vv 7, 17). This gave an earnestness to his exhortation that believers keep their minds clear and sober for prayer.

By steadily drawing upon God in prayer, Christians find the help they need to love each other and to overlook many offensive things (cf. Eph 4:1-3). This love should manifest itself in joyful hospitality, especially important in times of persecution (1 Pt 4:9), and should move believers to use all their varied gifts and talents to build each other up in faith (v 10). Two examples are given: speaking and ministering (the work of the preacher and the work of the deacon). Most important in speaking and ministering is to recognize what the goal of these gifts is and how to reach that goal. The goal is “that in all things God may be praised” (v 11). This may be done by recognizing that he gives the strength for service and the words for edifying speech.

4:12-19

Here the situation of suffering and bearing reproach for being Christians is again in view. The prospect of a “painful trial” (v 12) is impending (cf. 1:6-7). Peter saw these sufferings (probably from hostile associates rather than official state persecution) as God’s judgment on the world, beginning with the church (vv 17-18; cf. Prv 11:31). But God’s judgment on the church is not punitive but purgative (1 Pt 4:14; cf. 1:6-7).

Peter gives a reminder that suffering is a normal Christian experience (v 19; cf. 3:14; Acts 14:22; 1 Thes 3:3) and that Christ himself was so mistreated (1 Pt 2:21-25; Mt 10:25). Christians are encouraged to entrust their souls to a faithful Creator (1 Pt 4:19), to rejoice (v 13), and to persevere in doing good (v 19), thereby glorifying God (v 16). When believers respond to suffering in this way, they are blessed (v 14), for God manifests himself to them in an intimate and reassuring way.

5:1-7

Again (as in 3:8; 4:7-11) Peter treats relations within the church. He tells the elders how to be good shepherds of the flock (5:1-4), the younger people how to treat their elders (v 5), and everyone how to be humble toward each other.

Peter reminds believers that God opposes the proud but gives grace to the lowly (v 5; cf. Mt 23:12; Jas 4:6), whom he will exalt in the age to come (1 Pt 5:6; cf. Lk 14:11; 18:14; Jas 4:10). Most important, God invites his people to throw all their anxieties on him because he cares for them (1 Pt 5:7; cf. Ps 55:22; Mt 6:25-30).

The young people who are thus made humble will be subject to their elders and respect them (1 Pt 5:5). The elders who are thus made humble will not lord it over the flock (v 3) or be greedy or begrudging in their service (v 2), but will lead the flock by a humble example.

5:8-11

Peter returns to his concern with suffering. Suffering is the universal lot of believers (v 9; cf. 4:12). Although in one sense willed by God (1:6; 3:17; 4:19), it is used by Satan to try to destroy their faith. So Peter appeals to the church to be wakeful and sober (5:8; cf. 1:13; 4:7) so that they can resist the lion by faith.

5:12-14

In conclusion, Peter describes his “brief” writing as an exhortation and a testimony concerning the true grace of God. So the letter is not a call for hard labor for God; rather, it is a call to recognize, enjoy, and live by the hard labor that God graciously has exerted and will exert for his children. As was noted above, the letter was written by Silas (Greek Silvanus, probably the same person as in Acts 16:25; 1 Thes 1:1; 2 Thes 1:1). It was written from Rome, and greetings were sent from Mark (probably the Gospel writer and former missionary companion of Paul—Acts 13:13; 15:37; 2 Tm 4:11) and the whole church. Peter’s last word is to invoke peace upon the churches and to urge them to keep the affection warm among themselves.

See also Suffering; Peter, the Apostle; Spirits in Prison.